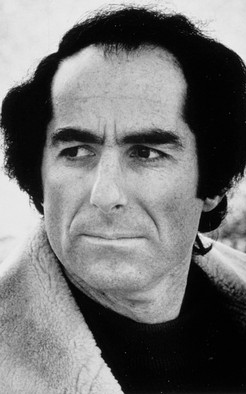

Philip Roth

Philip Milton Roth (March 19, 1933 – May 22, 2018)[1] was an American novelist and short-story writer. Roth's fiction—often set in his birthplace of Newark, New Jersey—is known for its intensely autobiographical character, for philosophically and formally blurring the distinction between reality and fiction, for its "sensual, ingenious style" and for its provocative explorations of American identity.[2] He first gained attention with the 1959 short story collection Goodbye, Columbus, which won the U.S. National Book Award for Fiction.[3][4] Ten years later, he published the bestseller Portnoy's Complaint. Nathan Zuckerman, Roth's literary alter ego, narrates several of his books. A fictionalized Philip Roth narrates some of his others, such as the alternate history The Plot Against America.

For other people with similar names, see Phillip Roth.

Philip Roth

Philip Milton Roth

March 19, 1933

Newark, New Jersey, U.S.

May 22, 2018 (aged 85)

New York City, U.S.

Bard College Cemetery

Novelist

1959–2010

-

Margaret Martinson Williams(m. 1959; div. 1963)

Roth was one of the most honored American writers of his generation.[5] He received the National Book Critics Circle award for The Counterlife, the PEN/Faulkner Award for Operation Shylock, The Human Stain, and Everyman, a second National Book Award for Sabbath's Theater, and the Pulitzer Prize for American Pastoral. In 2005, the Library of America began publishing his complete works, making him the second author so anthologized while still living, after Eudora Welty.[6] Harold Bloom named him one of the four greatest American novelists of his day, along with Cormac McCarthy, Thomas Pynchon, and Don DeLillo. In 2001, Roth received the inaugural Franz Kafka Prize in Prague.

Personal life[edit]

While at Chicago in 1956, Roth met Margaret Martinson, who became his first wife in 1959. Their separation in 1963, and Martinson's subsequent death in a car crash in 1968, left a lasting mark on Roth's literary output. Martinson was the inspiration for female characters in several of Roth's novels, including Lucy Nelson in When She Was Good and Maureen Tarnopol in My Life as a Man.[35]

Roth was an atheist who once said, "When the whole world doesn't believe in God, it'll be a great place."[36][37] He also said during an interview with The Guardian: "I'm exactly the opposite of religious, I'm anti-religious. I find religious people hideous. I hate the religious lies. It's all a big lie," and "It's not a neurotic thing, but the miserable record of religion—I don't even want to talk about it. It's not interesting to talk about the sheep referred to as believers. When I write, I'm alone. It's filled with fear and loneliness and anxiety—and I never needed religion to save me."[38]

In 1990 Roth married his longtime companion, English actress Claire Bloom, with whom he had been living since 1976. When Bloom asked him to marry her, "cruelly, he agreed, on condition that she signed a pre-nuptial agreement that would give her very little in the event of a divorce—which he duly demanded two years later." He also stipulated that Bloom's daughter Anna Steiger—from her marriage to Rod Steiger—not live with them.[39] They divorced in 1994, and Bloom published a 1996 memoir, Leaving a Doll's House, that depicted Roth as a misogynist and control freak. Some critics have detected parallels between Bloom and the character Eve Frame in Roth's I Married a Communist (1998).[13]

The novel Operation Shylock (1993) and other works draw on a post-operative breakdown[40][41][42] and Roth's experience of the temporary side effects of the sedative Halcion (triazolam), prescribed post-operatively in the 1980s.[43][44]

Death and burial[edit]

Roth died at a Manhattan hospital of heart failure on May 22, 2018, at the age of 85.[45][13][46] Roth was buried at the Bard College Cemetery in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, where in 1999 he taught a class. He had originally planned to be buried next to his parents at the Gomel Chesed Cemetery in Newark, but changed his mind about 15 years before his death, in order to be buried close to his friend Norman Manea.[47] Roth expressly banned any religious rituals from his funeral service, though it was noted that, the day after his burial, a pebble had been placed on top of his tombstone in accordance with Jewish tradition.[48]

Legacy[edit]

John Updike, considered by many Roth's chief literary rival, said in 2008, "He's scarily devoted to the novelist's craft... [he] seems more dedicated in a way to the act of writing as a means of really reshaping the world to your liking. But he's been very good to have around as far as goading me to become a better writer." Roth spoke at Updike's memorial service, saying, "He is and always will be no less a national treasure than his 19th-century precursor, Nathaniel Hawthorne."[83] After Updike's memorial at the New York Public Library, Roth told Charles McGrath, "I dream about John sometimes. He's standing behind me, watching me write." Asked who was better, Roth said, "John had more talent, but I think maybe I got more out of the talent I had." McGrath agreed with that assessment, adding that Updike might be the better stylist, but Roth's work was more consistent and "much funnier". McGrath added that in the 1990s Roth "underwent a kind of sea change and, borne aloft by that extraordinary second wind, produced some of his very best work": Sabbath's Theater and the American Trilogy (American Pastoral, I Married a Communist, and The Human Stain).[84] Another admirer of Roth's work is Bruce Springsteen. Roth read Springsteen's autobiography, Born to Run, and Springsteen praised Roth's American Trilogy: "I'll tell you, those three recent books by Philip Roth just knocked me on my ass.... To be in his sixties making work that is so strong, so full of revelations about love and emotional pain, that's the way to live your artistic life. Sustain, sustain, sustain."[85]

Roth left his book collection and more than $2 million to the Newark Public Library.[86][87] In 2021, the Philip Roth Personal Library opened for public viewing in the Newark Public Library.[88] In April 2021, W. W. Norton & Company published Blake Bailey's authorized biography of Roth, Philip Roth: The Biography. Publication was halted two weeks after release due to sexual assault allegations against Bailey.[89][90][91][92] Three weeks later, in May 2021, Skyhorse Publishing announced that it would release a paperback, ebook, and audiobook versions of the biography.[93] Roth had asked his executors "to destroy many of his personal papers after the publication of the semi-authorized biography on which Blake Bailey had recently begun work.... Roth wanted to ensure that Bailey, who was producing exactly the type of biography he wanted, would be the only person outside a small circle of intimates permitted to access personal, sensitive manuscripts, including the unpublished Notes for My Biographer (a 295-page rebuttal to his ex-wife's memoir) and Notes on a Slander-Monger (another rebuttal, this time to a biographical effort from Bailey's predecessor). 'I don't want my personal papers dragged all over the place,' Roth said. The fate of Roth's personal papers took on new urgency in the wake of Norton's decision to halt distribution of the biography. In May 2021, the Philip Roth Society published an open letter[94] imploring Roth's executors 'to preserve these documents and make them readily available to researchers.'"[95][96][97]

After Roth's passing, Harold Bloom told the Library of America: "Philip Roth's departure is a dark day for me and for many others. His two greatest novels, American Pastoral and Sabbath's Theater, have a controlled frenzy, a high imaginative ferocity, and a deep perception of America in the days of its decline. The Zuckerman tetralogy remains fully alive and relevant, and I should mention too the extraordinary invention of Operation Shylock, the astonishing achievement of The Counterlife, and the pungency of The Plot Against America. His My Life as a Man still haunts me. In one sense Philip Roth is the culmination of the unsolved riddle of Jewish literature in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. The complex influences of Kafka and Freud and the malaise of American Jewish life produced in Philip a new kind of synthesis. Pynchon aside, he must be estimated as the major American novelist since Faulkner."[98]

In The New Yorker, James Wood wrote: "More than any other post-war American writer, Roth wrote the self—the self was examined, cajoled, lampooned, fictionalized, ghosted, exalted, disgraced but above all constituted by and in writing. Maybe you have to go back to the very different Henry James to find an American novelist so purely a bundle of words, so restlessly and absolutely committed to the investigation and construction of life through language... He would not cease from exploration; he could not cease, and the varieties of fiction existed for him to explore the varieties of experience."[99] The New York Times asked several prominent authors to name their favorite work by Roth. The responses were varied; Jonathan Safran Foer chose Patrimony, Roth's memoir of his father's illness: "Much has been written about Roth since he died. In keeping with the unseemliness of our profession, we all have something to say. The responses have overflowed with a kind of blunt adoration that would be perfectly un-Rothlike if they weren't the efforts of children agonizing over the right way to bury our father. None of it feels right, perhaps because nothing could. Roth's words dressed his father for death, and they dressed so many of us for life. How does one properly acknowledge that? How does one say thank you for the thousand almost-invisible preparations? This morning, as I was getting my children dressed for school, I felt the profound gratitude of a 'little son.'"[100]

Joyce Carol Oates told The Guardian: "Philip Roth was a slightly older contemporary of mine. We had come of age in more or less the same repressive 50s era in America—formalist, ironic, 'Jamesian', a time of literary indirection and understatement, above all impersonality—as the high priest TS Eliot had preached: 'Poetry is an escape from personality.' Boldly, brilliantly, at times furiously, and with an unsparing sense of the ridiculous, Philip repudiated all that. He did revere Kafka—but Lenny Bruce as well. (In fact, the essential Roth is just that anomaly: Kafka riotously interpreted by Lenny Bruce.) But there was much more to Philip than furious rebellion. For at heart he was a true moralist, fired to root out hypocrisy and mendacity in public life as well as private. Few saw The Plot Against America as actual prophecy, but here we are. He will abide."[101]