Chemical weapons in World War I

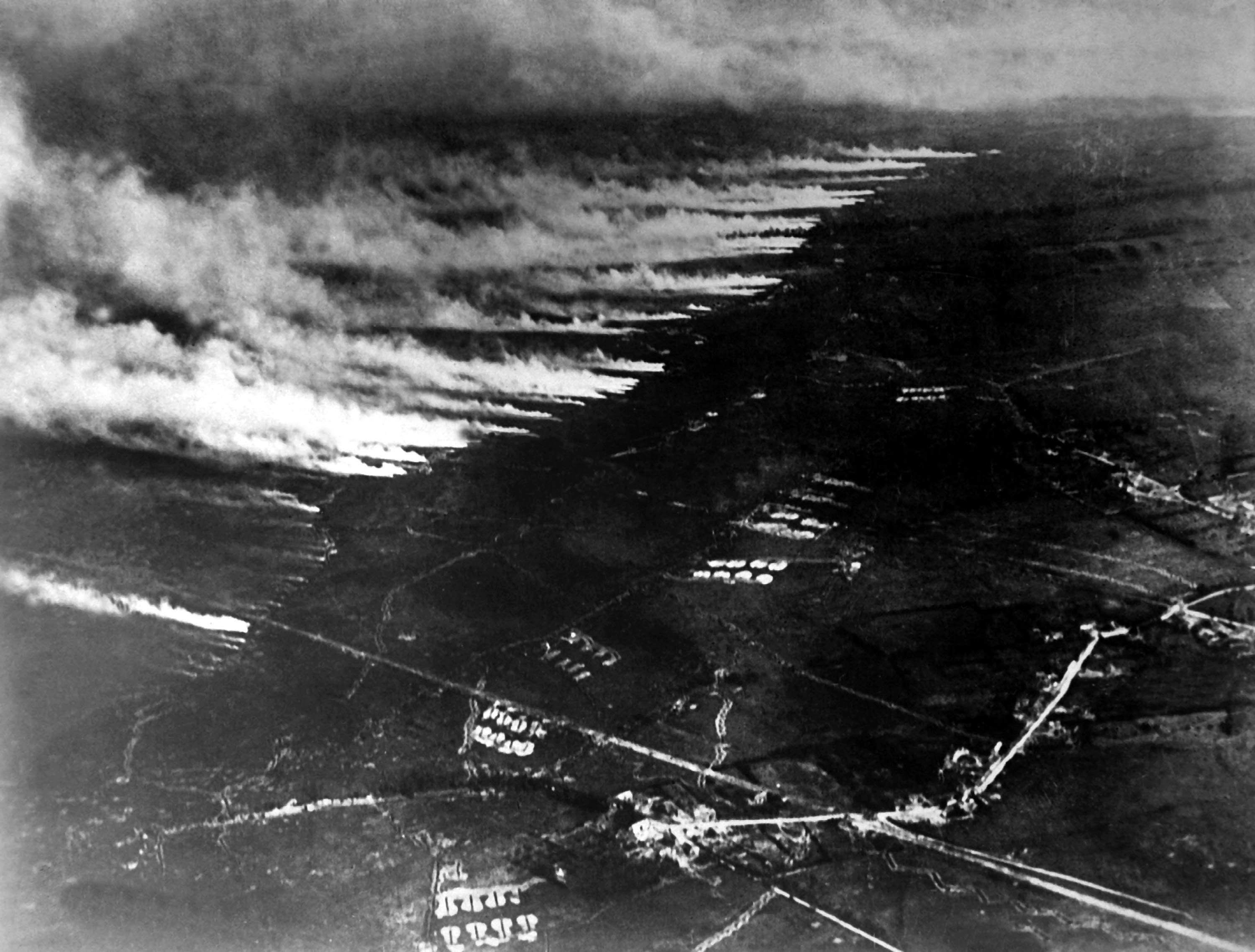

The use of toxic chemicals as weapons dates back thousands of years, but the first large-scale use of chemical weapons was during World War I.[1][2] They were primarily used to demoralize, injure, and kill entrenched defenders, against whom the indiscriminate and generally very slow-moving or static nature of gas clouds would be most effective. The types of weapons employed ranged from disabling chemicals, such as tear gas, to lethal agents like phosgene, chlorine, and mustard gas. These chemical weapons caused medical problems.[3] This chemical warfare was a major component of the first global war and first total war of the 20th century. The killing capacity of gas was profound, with about 90,000 fatalities from a total of 1.3 million casualties caused by gas attacks. Gas was unlike most other weapons of the period because it was possible to develop countermeasures, such as gas masks. In the later stages of the war, as the use of gas increased, its overall effectiveness diminished. The widespread use of these agents of chemical warfare, and wartime advances in the composition of high explosives, gave rise to an occasionally expressed view of World War I as "the chemist's war" and also the era where weapons of mass destruction were created.[4][5]

The use of poison gas by all major belligerents throughout World War I constituted war crimes as its use violated the 1899 Hague Declaration Concerning Asphyxiating Gases and the 1907 Hague Convention on Land Warfare, which prohibited the use of "poison or poisoned weapons" in warfare.[6][7] Widespread horror and public revulsion at the use of gas and its consequences led to far less use of chemical weapons by combatants during World War II.

None of the First World War's combatants were prepared for the introduction of poison gas as a weapon. Once gas was introduced, development of gas protection began and the process continued for much of the war, producing a series of increasingly effective gas masks.[52]

Even at Second Ypres, Germany, still unsure of the weapon's effectiveness, only issued breathing masks to the engineers handling the gas. At Ypres a Canadian medical officer, who was also a chemist, quickly identified the gas as chlorine and recommended that the troops urinate on a cloth and hold it over their mouth and nose, urine would be left to sit for a period so that the ammonia would activate, this would neutralize some of the chemicals in the chlorine gas, this action would allow them to delay the German advance at Ypres giving the allies time to reinforce the area when French and other colonial troops had retreated.[83] The first official equipment issued was similarly crude; a pad of material, usually impregnated with a chemical, tied over the lower face. To protect the eyes from tear gas, soldiers were issued with gas goggles.

The next advance was the introduction of the gas helmet—basically a bag placed over the head. The fabric of the bag was impregnated with a chemical to neutralize the gas—the chemical would wash out into the soldier's eyes whenever it rained. Eye-pieces, which were prone to fog up, were initially made from talc. When going into combat, gas helmets were typically worn rolled up on top of the head, to be pulled down and secured about the neck when the gas alarm was given. The first British version was the hypo helmet, the fabric of which was soaked in sodium hyposulfite (commonly known as "hypo"). The British P gas helmet, partially effective against phosgene and with which all infantry were equipped with at Loos, was impregnated with sodium phenolate. A mouthpiece was added through which the wearer would breathe out to prevent carbon dioxide build-up. The adjutant of the 1/23rd Battalion, The London Regiment, recalled his experience of the P helmet at Loos:

A modified version of the P helmet, called the PH helmet, was issued in January 1916, and was impregnated with hexamethylenetetramine to improve protection against phosgene.[33]

Self-contained box respirators represented the culmination of gas mask development during the First World War. Box respirators used a two-piece design; a mouthpiece connected via a hose to a box filter. The box filter contained granules of chemicals that neutralised the gas, delivering clean air to the wearer. Separating the filter from the mask enabled a bulky but efficient filter to be supplied. Nevertheless, the first version, known as the large box respirator (LBR) or "Harrison's Tower", was deemed too bulky—the box canister needed to be carried on the back. The LBR had no mask, just a mouthpiece and nose clip; separate gas goggles had to be worn. It continued to be issued to the artillery gun crews but the infantry were supplied with the "small box respirator" (SBR).

The Small Box Respirator featured a single-piece, close-fitting rubberized mask with eye-pieces. The box filter was compact and could be worn around the neck. The SBR could be readily upgraded as more effective filter technology was developed. The British-designed SBR was also adopted for use by the American Expeditionary Force. The SBR was the prized possession of the ordinary infantryman; when the British were forced to retreat during the German spring offensive of 1918, it was found that while some troops had discarded their rifles, hardly any had left behind their respirators.

Horses and mules were important methods of transport that could be endangered if they came into close contact with gas. This was not so much of a problem until it became common to launch gas great distances. This caused researchers to develop masks that could be used on animals such as dogs, horses, mules, and even carrier pigeons.[85]

For mustard gas, which could cause severe damage by simply making contact with skin, no effective countermeasure was found during the war. The kilt-wearing Scottish regiments were especially vulnerable to mustard gas injuries due to their bare legs. At Nieuwpoort in Flanders some Scottish battalions took to wearing women's tights beneath the kilt as a form of protection.

Gas alert procedure became a routine for the front-line soldier. To warn of a gas attack, a bell would be rung, often made from a spent artillery shell. At the noisy batteries of the siege guns, a compressed air strombus horn was used, which could be heard nine miles (14 km) away. Notices would be posted on all approaches to an affected area, warning people to take precautions.

Other British attempts at countermeasures were not so effective. An early plan was to use 100,000 fans to disperse the gas. Burning coal or carborundum dust was tried. A proposal was made to equip front-line sentries with diving helmets, air being pumped to them through a 100 ft (30 m) hose.

The effectiveness of all countermeasures is apparent. In 1915, when poison gas was relatively new, less than 3% of British gas casualties died. In 1916, the proportion of fatalities jumped to 17%. By 1918, the figure was back below 3%, though the total number of British gas casualties was now nine times the 1915 levels.