Polish population transfers (1944–1946)

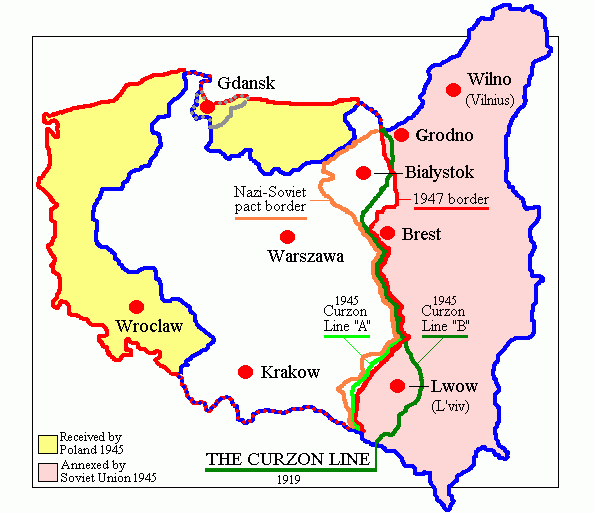

The Polish population transfers in 1944–1946 from the eastern half of prewar Poland (also known as the expulsions of Poles from the Kresy macroregion),[1] were the forced migrations of Poles toward the end and in the aftermath of World War II. These were the result of a Soviet Union policy that had been ratified by the main Allies of World War II. Similarly, the Soviet Union had enforced policies between 1939 and 1941 which targeted and expelled ethnic Poles residing in the Soviet zone of occupation following the Nazi-Soviet invasion of Poland. The second wave of expulsions resulted from the retaking of Poland from the Wehrmacht by the Red Army. The USSR took over territory for its western republics.

The postwar population transfers were part of an official Soviet policy that affected more than one million Polish citizens, who were removed in stages from the Polish areas annexed by the Soviet Union. After the war, following Soviet demands laid out during the Tehran Conference of 1943, Kresy was formally incorporated into the Ukrainian, Belarusian and Lithuanian republics of the Soviet Union. This was agreed at the Potsdam Conference of Allies in 1945, to which the Polish government-in-exile was not invited.[2]

The ethnic displacement of Poles (and also of ethnic Germans) was agreed between the Allied leaders Winston Churchill of the United Kingdom, Franklin D. Roosevelt of the U.S., and Joseph Stalin of the USSR, during the conferences at Tehran and Yalta. The Polish transfers were among the largest of several post-war expulsions in Central and Eastern Europe, which displaced a total of about 20 million people.

According to official data, during the state-controlled expulsion between 1945 and 1946, roughly 1,167,000 Poles left the westernmost republics of the Soviet Union, less than 50% of those who registered for population transfer. Another major ethnic Polish transfer took place after Stalin's death, in 1955–1959.[3]

The process is variously known as expulsion,[1] deportation,[4][5] depatriation,[6][7][8] or repatriation,[9] depending on the context and the source. The term repatriation, used officially in both the Polish People's Republic and the USSR, was a deliberate distortion,[10][11] as deported peoples were leaving their homeland rather than returning to it.[6] It is also sometimes referred to as the 'first repatriation' action, in contrast with the 'second repatriation' of 1955–1959. In a wider context, it is sometimes described as a culmination of a process of de-Polonization of these areas during and after the world war.[12] The process was planned and carried out by the communist regimes of the USSR and of post-war Poland. Many of the deported Poles were settled in historical eastern Germany; after 1945, these were referred to as the "Recovered Territories" of the Polish People's Republic.

Background[edit]

The history of ethnic Polish settlement in what is now Ukraine and Belarus dates to 1030–31. More Poles migrated to this area after the Union of Lublin in 1569, when most of the territory became part of the newly established Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. From 1657 to 1793, some 80 Roman Catholic churches and monasteries were built in Volhynia alone. The expansion of Catholicism in Lemkivshchyna, Chełm Land, Podlaskie, Brześć land, Galicia, Volhynia and Right bank Ukraine was accompanied by the process of gradual Polonization of the eastern lands. Social and ethnic conflicts arose regarding the differences in religious practices between the Roman Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox adherents during the Union of Brest in 1595-96, when the Metropolitan of Kyiv-Halych broke relations with the Eastern Orthodox Church and accepted the authority of the Roman Catholic Pope and Vatican.[13]

The partitions of Poland, toward the end of the 18th century, resulted in the expulsions of ethnic Poles from their homes in the east for the first time in the history of the nation. Some 80,000 Poles were escorted to Siberia by the Russian imperial army in 1864 in the single largest deportation action undertaken within the Russian Partition.[14] "Books were burned; churches destroyed; priests murdered;" wrote Norman Davies.[15] Meanwhile, Ukrainians were officially considered "part of the Russian people".[16][17]

The Russian Revolution of 1917 and the Russian Civil War of 1917-1922 brought an end to the Russian Empire.[18] According to Ukrainian sources from the Cold War period, during the Bolshevik revolution of 1917 the Polish population of Kyiv was 42,800.[19] In July 1917, when relations between the Ukrainian People's Republic (UNR) and Russia became strained, the Polish Democratic Council of Kyiv supported the Ukrainian side in its conflict with Petrograd. Throughout the existence of UNR (1917–21), there was a separate ministry for Polish affairs, headed by Mieczysław Mickiewicz; it was set up by the Ukrainian side in November 1917. In that entire period, some 1,300 Polish-language schools were operating in Galicia, with 1,800 teachers and 84,000 students. In the region of Podolia in 1917, there were 290 Polish schools.

Beginning in 1920, the Bolshevik and nationalist terror campaigns of the new war triggered the flight of Poles and Jews from Soviet Russia to newly sovereign Poland. In 1922 Bolshevik Russian Red Army, with their Bolshevik allies in Ukraine overwhelmed the government of the Ukrainian People's Republic, including the annexed Ukrainian territories into the Soviet Union. In that year, 120,000 Poles stranded in the east were expelled to the west and the Second Polish Republic.[20] The Soviet census of 1926 recorded ethnic Poles as being of Russian or Ukrainian ethnicity, reducing their apparent numbers in Ukraine.[21]: 7

In the autumn of 1935, Stalin ordered a new wave of mass deportations of Poles from the western republics of the Soviet Union. This was also the time of his purges of different classes of people, many of whom were killed. Poles were expelled from the border regions to resettle the area with ethnic Russians and Ukrainians, but Stalin had them deported to the far reaches of Siberia and Central Asia. In 1935 alone 1,500 families were deported to Siberia from Soviet Ukraine. In 1936, 5,000 Polish families were deported to Kazakhstan. The deportations were accompanied by the gradual elimination of Polish cultural institutions. Polish-language newspapers were closed, as were Polish-language classes throughout Ukraine.

Soon after the wave of deportations, the Soviet NKVD orchestrated the Polish Operation. The Polish population in the USSR had officially dropped by 165,000 in that period according to the official Soviet census of 1937–38; Polish population in the Ukrainian SSR decreased by about 30%.[22][23]

Second Polish Republic[edit]

Amidst several border conflicts, Poland re-emerged as a sovereign state in 1918 following Partitions of Poland. The Polish-Ukrainian alliance was unsuccessful, and the Polish-Soviet war continued until the Treaty of Riga was signed in 1921. The Soviet Union did not officially exist before 31 December 1922.[24] The disputed territories were split in Riga between the Second Polish Republic and the Soviet Union representing Ukrainian SSR (part of the Soviet Union after 1923). In the following few years in Kresy, the lands assigned to sovereign Poland, some 8,265 Polish farmers were resettled with help from the government.[25] The overall number of settlers in the east was negligible as compared to the region's long-term residents. For instance in the Volhynian Voivodeship (1,437,569 inhabitants in 1921), the number of settlers did not exceed 15,000 people (3,128 refugees from Bolshevist Russia, roughly 7,000 members of local administration, and 2,600 military settlers).[25] Approximately 4 percent of the newly arrived settlers lived on land granted to them. The majority either rented their land to local farmers, or moved to the cities.[25][26]

Tensions between the Ukrainian minority in Poland and the Polish government escalated. On 12 July 1930, activists of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), helped by the UVO, began the so-called sabotage action, during which Polish estates were burned, and roads, rail lines and telephone connections were destroyed. The OUN used terrorism and sabotage in order to force the Polish government into actions that would cause a loss of support for the more moderate Ukrainian politicians ready to negotiate with the Polish state.[27] OUN directed its violence not only against the Poles but also against Jews and other Ukrainians who wished for a peaceful resolution to the Polish–Ukrainian conflict.[28]