Pragmatic ethics

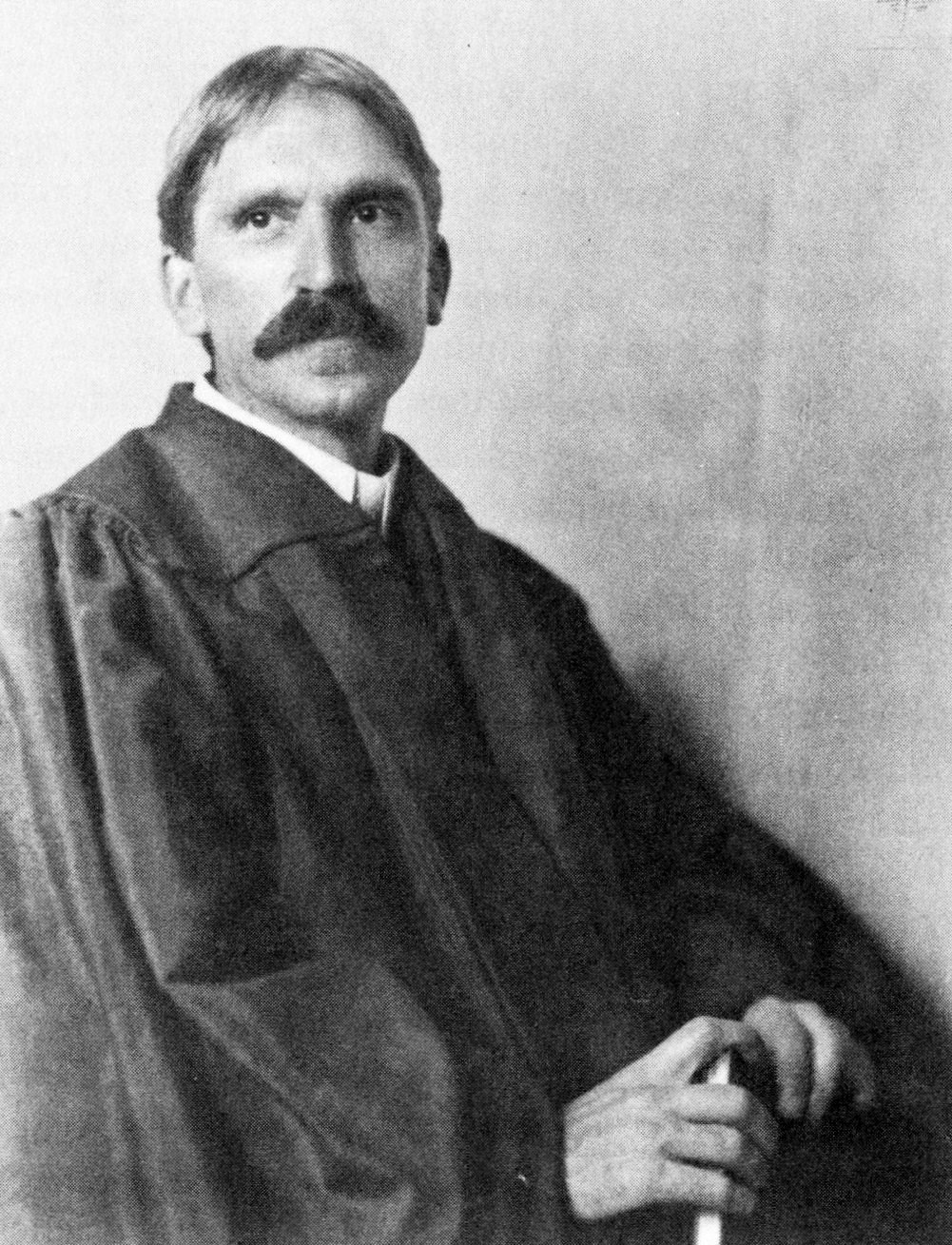

Pragmatic ethics is a theory of normative philosophical ethics and meta-ethics. Ethical pragmatists such as John Dewey believe that some societies have progressed morally in much the way they have attained progress in science. Scientists can pursue inquiry into the truth of a hypothesis and accept the hypothesis, in the sense that they act as though the hypothesis were true; nonetheless, they think that future generations can advance science, and thus future generations can refine or replace (at least some of) their accepted hypotheses. Similarly, ethical pragmatists think that norms, principles, and moral criteria are likely to be improved as a result of inquiry.

Martin Benjamin used Neurath's boat as an analogy for pragmatic ethics, likening the gradual change of ethical norms to the reconstruction of a ship at sea by its sailors.[1]

Criticisms[edit]

Pragmatic ethics has been criticized for conflating descriptive ethics with normative ethics, as describing the way people do make moral judgments rather than the way they should make them, or in other words for lacking normative standards.[11] While some ethical pragmatists may have avoided the distinction between normative and descriptive truth, the theory of pragmatic ethics itself does not conflate them any more than science conflates truth about its subject matter with current opinion about it; in pragmatic ethics as in science, "truth emerges from the self-correction of error through a sufficiently long process of inquiry".[2] A normative criterion that many pragmatists emphasize is the degree to which the process of social learning is deliberatively democratic:[12] "while deontologists focus on moral duties and obligations and utilitarians on the greatest happiness of the greatest number, pragmatists concentrate on coexistence and cooperation".[13]