Randolph Churchill

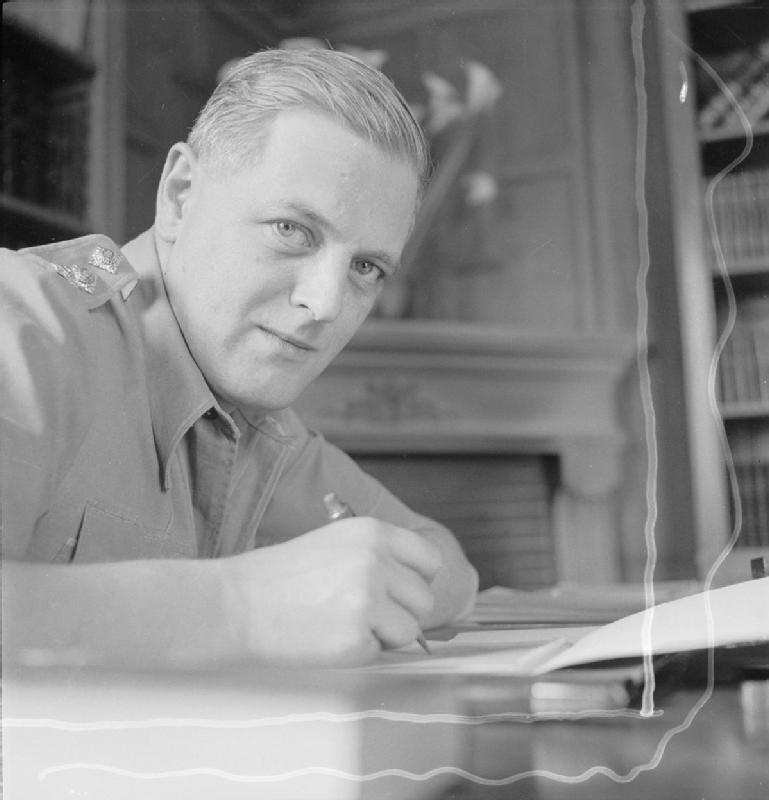

Major Randolph Frederick Edward Spencer Churchill[a] MBE (28 May 1911 – 6 June 1968) was an English journalist, writer and politician.

This article is about the son of Winston Churchill. For his grandfather, and Winston Churchill's father, see Lord Randolph Churchill.

Randolph Churchill

28 May 1911

London, England

6 June 1968 (aged 57)

East Bergholt, Suffolk, England

-

June Osborne(m. 1948; div. 1961)

- Journalist

- soldier

United Kingdom

1938–1961

The only son of future British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and his wife, Clementine, Randolph was brought up to regard himself as his father's political heir, although their relations became strained in later years. In the 1930s, he stood unsuccessfully for Parliament a number of times, causing his father embarrassment. He was elected as Conservative Member of Parliament (MP) for Preston at the 1940 Preston by-election. During the Second World War, he served with the SAS in North Africa and with Tito's partisans in Yugoslavia. Randolph lost his seat in 1945 and was never re-elected to Parliament. Despite his lack of success in politics, Randolph enjoyed a successful career as a writer and journalist. In the 1960s, he wrote the first two volumes of the official life of his father.

Randolph was married and divorced twice. His first wife was Pamela Digby (later Harriman); their son Winston later became a Conservative MP. Throughout his life, Randolph had a reputation for rude drunken behaviour. By the 1960s, his health had collapsed from years of heavy drinking; he outlived his father by only three years.

Childhood[edit]

Randolph Churchill was born at his parents' house at Eccleston Square, London, on 28 May 1911.[1][b] His parents nicknamed him "the Chumbolly" before he was born.[c][1]

His father Winston Churchill was already a leading Liberal Cabinet Minister, and Randolph was christened in the House of Commons crypt on 26 October 1911, with Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey and Conservative politician F. E. Smith among his godparents.[4] Randolph and his older sister Diana had for a time to be escorted by plain clothes detectives on their walks in the park, because of threats by suffragettes to kidnap them.[5] He was a page at the marriage of the Prime Minister's daughter Violet Asquith to Maurice Bonham Carter on 1 December 1915.[6]

He recalled the Zeppelin raids of 1917 as "a great treat", as the children were taken from their beds in the middle of the night, wrapped in blankets, and "allowed" to join the grown-ups in the cellar;[7] he also recalled the Armistice celebrations at Blenheim Palace.[8]

He went to Sandroyd School in Wiltshire, and later admitted that he had had a problem with authority and discipline. His headmaster reported to his father that he was "very combative". Winston, who had been neglected by his parents as a small boy, visited his son at prep school as often as possible.[9] Randolph was very good-looking as a child and into his twenties. In his autobiography Twenty-One Years (pp. 24–25) he recorded that at the age of ten he had been "interfered with" by a junior prep school master, who made Randolph touch him sexually, only to leap embarrassed to his feet when a matron came in. At home, a maid overheard Randolph confiding in his sister Diana. He later wrote that he had never seen his father so angry, and that he had made a hundred-mile trip to demand that the teacher be dismissed, only to learn that the teacher had already been sacked.[10][11]

He remembered that he and Diana returned from ice-skating in Holland Park on 22 June 1922 to find the house guarded and being searched by "tough-looking men" following the assassination of Field Marshal Henry Wilson.[12]

Eton[edit]

Winston gave his son a choice of Eton College or Harrow School, and he chose the former.[13] Randolph later wrote "I was lazy and unsuccessful both at work and at games ... and was an unpopular boy".[14] He was once said to have been given "six up" (i.e. a beating) by his house's Captain of Games (a senior boy) for being "bloody awful all round". Michael Foot later wrote that this was "the kind of comprehensive verdict which others who had dealings with him were always searching for."[15] He once wrote apologising to his father for "having done so badly and disappointed you so much".[16] During the general strike of 1926 he fixed up a secret radio set as his housemaster would not allow him to have one.[12] In November 1926 his headmaster wrote to his father to inform him that he had caned Randolph, then aged 15, after all five of the masters then teaching him had independently reported him for "either being idle or being a bore with his chatter".[17]

As a teenager Randolph fell in love with Diana Mitford, sister of his friend Tom Mitford.[18] Tom Mitford was regarded as having a calming influence on him,[19] although his housemaster Colonel Sheepshanks[20] wrongly suspected Randolph and Tom of being lovers; Randolph replied, "I happen to be in love with his sister".[21]

Randolph was "a loquacious and precocious boy".[22] From his teenage years he was encouraged to attend his father's dinner parties with leading politicians of the day, drink and have his say, and he later recorded that he would simply have laughed at anyone who had suggested that he would not go straight into politics and perhaps even become Prime Minister by his mid-twenties like William Pitt the Younger.[23][13] His sister later wrote that he "manifestly needed a father's hand" but his father "spoiled and indulged him", and did not take seriously the complaints of his schoolmasters. He was influenced by his godfather Lord Birkenhead (F. E. Smith), an opinionated and heavy-drinking man.[12] Winston Churchill was Chancellor of the Exchequer from late 1924 until 1929. Busy in that office, he neglected his daughters in favour of Randolph, who was his only son.[13] On a visit to Italy in 1927 Winston and Randolph were received by Pope Pius XI.[13] In later life "relations between Winston and Randolph were always uneasy, the father alternately spoiling and being infuriated by the son."[22]

In April 1928 Winston forwarded a satisfactory school report to Clementine, who was in Florence, commenting that Randolph was "developing fast" and would be fit for politics, the bar or journalism and was "far more advanced than I was at his age". His mother replied that "He is certainly going to be an interest, an anxiety & an excitement in our lives".[12] He had cool relations with his mother from an early age, in part because she felt him to be spoiled and arrogant as a result of his father's overindulgence.[13][23] Clementine's biographer writes that "Randolph was for decades a recurrent embarrassment to both his parents".[24]

In what would turn out to be his final report on leaving Eton, Robert Birley, one of his history teachers, wrote of his native intelligence and writing ability, but added that he found it too easy to get by on little work or with a journalist's knack of spinning a single idea into an essay.[25]

Oxford[edit]

Randolph went up to Christ Church, Oxford, in January 1929, partway through the academic year and not yet eighteen, after his father's friend Professor Lindemann had advised that a place had fallen vacant.[26]

In May he spoke for his father at the May 1929 general election.[27][28] Between August and October 1929 Randolph and his uncle accompanied his father (now out of office) on his lecture tour of the US and Canada.[29][28] His diary of the trip was later included in Twenty-One Years. On one occasion he impressed his father by delivering an impromptu five-minute reply to a tedious speech by a local cleric. At San Simeon (the mansion of press baron Randolph Hearst) he lost his virginity to the Austrian-born actress Tilly Losch[30] an erstwhile lover of his close friend Tom Mitford.

Randolph was already drinking double brandies at the age of nineteen, to his parents' consternation.[22] He did little work or sport at Oxford and spent most of his time at lengthy lunch and dinner parties with other well-connected undergraduates and with dons who enjoyed being entertained by them. Randolph later claimed that he had benefited from the experience, but at the time his lifestyle earned him a magisterial letter of rebuke from his father (29 December 1929), warning him that he was "not acquiring any habits of industry or concentration" and that he would withdraw him from Oxford if he did not knuckle down to study. Winston Churchill had also received a similar and oft-quoted letter of rebuke from his own father, Lord Randolph Churchill, at almost exactly the same age.[31]

Speaking tour of the United States[edit]

Randolph dropped out of Oxford in October 1930 to conduct a lecture tour of the US.[16] He was already in debt; his mother guessed correctly that he would never finish his degree.[12] Contrary to his later claims, his father attempted to dissuade him at the time.[32]

Unlike his father, who had become a powerful orator through much practice, and whose speeches always required extensive preparation, public speaking came easily to Randolph. His son later recorded that this was a mixed blessing: "because of the very facility with which he could speak extemporaneously [he] failed to make the effort required to bring him more success".[33]

Randolph very nearly married Kay Halle of Cleveland, Ohio, seven years his senior. His father wrote begging him not to be so foolish as to marry before he had established a career.[34] Clementine visited him in December, using money Winston had given her to buy a small car.[16] Contrary to newspaper reports that she had crossed the Atlantic to put a stop to the wedding,[16] she only learned of the engagement when she arrived.[12] She found Randolph, to her horror, living in an extravagant suite of hotel rooms, but was able to write to Miss Halle's father, who agreed that it would be unwise for their children to marry.[34]

Clementine wrote to her husband of one of Randolph's lectures "Frankly, it was not at all good" and commented that he should have had it well-practised by now, although she was impressed by his delivery.[16] She went home in April 1931, having enjoyed Randolph's company in New York.[16] She would later look back on the trip with nostalgia.[12]

Randolph's lecture tour earned him $12,000 (£2,500 at the then rate of exchange, roughly £150,000 at 2020 prices).[34][35] By the time of his mother's arrival he had already spent £1,000 in three months, despite being on a £400 annual parental allowance.[16] He left the US owing $2,000 to his father's friend, the financier Bernard Baruch; a debt which he did not repay for thirty years.[34]

Early 1930s[edit]

In October 1931 Randolph began a lecture tour of the UK. He lost £600 by betting wrongly on the results of the general election; his father paid his debts on condition he gave up his chauffeur-driven Bentley, a more extravagant car than his father drove.[36] In 1931 he shared Edward James's house in London with John Betjeman. By the early 1930s Randolph was working as a journalist for the Rothermere press.[16] He wrote in an article in 1932 that he planned to "make an immense fortune and become Prime Minister"[37] He warned that the Nazis meant war as early as March 1932 in his Daily Graphic column;[38] his son Winston later claimed that he was the first British journalist to warn about Hitler.[39]

In 1932 Winston Churchill had Philip Laszlo paint an idealised portrait of his son for his 21st birthday.[d][10] Winston Churchill organised a "Fathers and Sons" dinner at Claridge's for his birthday on 16 June 1932, with Lord Hailsham and his son Quintin Hogg, Lord Cranborne and Freddie Birkenhead, the son of Winston's late friend F. E. Smith.[40] Also present were Admiral of the Fleet Earl Beatty and his son, and Oswald Mosley (then still seen as a coming man).[16] That year Randolph flew into a rage with Lord Beaverbrook, when his Daily Express singled him out in a story on the sons of great men, which sneered that "major fathers as a rule breed minor sons, so our little London peacocks had better tone down their fine feathers." "The function of the gossip writer", said Randolph, "is not among those which commend themselves mostly highly to my generation" (in middle age Randolph would himself become a highly paid London gossip columnist).[41]

Randolph reported from the German elections in July 1932.[39] Randolph encouraged his father to try to meet Adolf Hitler in summer 1932 whilst he was retracing the Duke of Marlborough's march to Blenheim (Winston was writing the Duke's life at the time); the meeting fell through at the last minute as Hitler excused himself.[38] Randolph had an affair with Doris Castlerosse in 1932, causing a near fight with her husband. She later claimed to have had an affair with his father Winston in the mid 1930s, although Winston's biographer Andrew Roberts believes the latter claim unlikely to be true.[42][43]

Randolph, then aged just 21, was sent to Paraguay in August 1932 by Beaverbrook's Daily Express. Just after his arrival in Asunción, he conducted an interview with Major Arturo Bray Riquelme, Director of the Military School and Commander of the R.I. 6 "Boquerón", formed from the officers and cadets of the Paraguayan Military School; this report was published in the Daily Express on Thursday, 11 August 1932, when the R.I. 6 was in full preparation to depart or at the war front in the Chaco. Arturo Bray was highly requested by the British Press, as the English knew that Bray was a British officer, hero of World War I, awarded with the highest medals of bravery bestowed by Britain and France.[44][45][46]

At Lady Diana Cooper's fortieth birthday party in Venice that year a woman was deliberately burned on her hand with a cigarette by a thwarted lover, and Randolph sprang to her defence.[47]

Randolph also became embroiled in the controversy of the February 1933 King and Country debate at the Oxford Union Society. Three weeks after the Union had passed a pacifist motion, Randolph and his friend Lord Stanley proposed a resolution to delete the previous motion from the Union's records. After a poor speech from Stanley, the president, Frank Hardie, temporarily handed over the chair to the librarian and opposed the motion on behalf of the Union, a very unusual move. The minutes record that he received "a very remarkable ovation".[48] Randolph was then met by a barrage of hisses and stink bombs.[49] His speech, facing what the minutes describe as a "very antipathetic and even angry house" was "unfortunate in his manner and phrasing" and was met with "delighted jeers". He then attempted to withdraw the motion. Hardie was willing to permit this, but an ex-president pointed out from the floor that a vote of the whole house was required to allow a motion to be withdrawn. The request to withdraw was defeated by acclamation and the motion was then defeated by 750 votes to 138 (a far better attendance than the original debate had attained).[48] Randolph had persuaded a number of other former students, life members of the Union, to attend in the hope of carrying his motion.[50] A bodyguard of Oxford Conservatives and police escorted Churchill back to his hotel after the debate.[49] Sir Edward Heath recorded in his memoirs that after the debate some of the undergraduates had been intent on debagging him.[51][e] Winston Churchill wrote praising his son's courage in addressing a large, hostile audience, adding that "he was by no means cowed".[52]

Randolph's good looks and self-confidence soon brought him some success as a womaniser, but his attempt to seduce one young woman at Blenheim failed after she spent the night in bed for protection with his cousin Anita Leslie, while Randolph sat on the side of the bed talking at length of "when I am prime minister".[16] Randolph, who had been lucky not to be named in court as one of her lovers, also comforted a tearful Tilly Losch in public at Quaglino's after her divorce in 1934, to the amusement of the other diners and the waiters.[16]

In the 1930s, Winston's overindulgence of his son was one of several causes of coolness between him and Clementine.[10] Clementine several times threw him out of Chartwell after arguments; at one time Clementine told Randolph she hated him and never wanted to see him again.[53]

Military service[edit]

Early war, marriage and Parliament[edit]

In August 1938, Randolph Churchill joined his father's old regiment, the 4th Queen's Own Hussars, receiving a commission as a second lieutenant in the supplementary reserve,[70] and was called up for active service on 24 August 1939.[71][22][72][73] He was one of the oldest of the junior officers, and not popular with his peers. In order to win a bet, he walked the 106-mile round trip from their base in Hull to York and back in under 24 hours. He was followed by a car, both to witness the event and in case his blisters became too painful to walk further, and made it with around twenty minutes to spare. To his great annoyance, his brother officers did not pay up.[74]

On the outbreak of war, Randolph's father was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty. He sent Captain Lord Louis Mountbatten, along with Lieutenant Randolph Churchill, aboard HMS Kelly (which was based at Plymouth at the time) to Cherbourg to bring the Duke and Duchess of Windsor back to England from their exile. Randolph was on board the destroyer untidily attired in his 4th Hussars uniform; he had attached the spurs to his boots upside down. The Duke was mildly shocked[75] and insisted on bending down to fit Randolph's spurs correctly.[72]

Randolph was in love with Laura Charteris (she did not reciprocate) but his mistress at the time was the American actress Claire Luce, who often visited him in camp. He appears to have decided that as Winston's only son, it was his duty to marry and sire an heir in case he was killed, a common motivation among young men at the time. He quickly became engaged to Pamela Digby[72] in late September 1939.[76] It was rumoured that Randolph had proposed to eight women in the previous few weeks, and Pamela's friends and parents were not pleased about the match. She was charmed by Randolph's parents, both of whom warmed to her and felt she would be a good influence on him.[77] They were married in October 1939.[76] On their wedding night, Randolph read her chunks of Edward Gibbon's The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. She managed to become pregnant by the spring of 1940.[77]

In May 1940, Randolph's father, to whom he remained close both politically and socially, became Prime Minister, just as the Battle of France was beginning. In the summer of 1940, Winston Churchill's secretary, Jock Colville, wrote (Fringes of Power p. 207) "I thought Randolph one of the most objectionable people I had ever met: noisy, self-assertive, whining and frankly unpleasant. He did not strike me as intelligent. At dinner he was anything but kind to Winston, who adores him".[78] The polemic against appeasement Guilty Men (July 1940), in fact written anonymously by Michael Foot, Frank Owen, and Peter Howard, was wrongly attributed to Randolph Churchill.[79]

Randolph was elected unopposed to Parliament for Preston at a wartime by-election in September 1940.[80] Soon afterwards, his son Winston was born on 10 October 1940.[81][82] During the first year of marriage, Randolph had no home of his own until Brendan Bracken found them a vicarage at Ickleford, near Hitchin, Hertfordshire. Pamela often had to ask Winston to pay Randolph's gambling debts.[83]

North Africa[edit]

It was widely suspected, including by Randolph himself, that secret orders had been given that the 4th Hussars were not to be sent into action (they were, as soon as Randolph transferred out). Randolph transferred to No. 8 (Guards) Commando. In February 1941 they were sent out, a six-week journey via the Cape of Good Hope and the East Coast of Africa, avoiding the Central Mediterranean where the Italian navy and Axis air forces were strong. Randolph, who was still earning £1,500 per annum as a Lord Beaverbrook journalist, lost £3,000 gambling on the voyage. Pamela had to go to Beaverbrook, who refused her an advance on Randolph's salary. Declining his offer of an outright gift (it is unclear whether submitting to his sexual advances was a condition), she sold her wedding presents, including jewellery; took a job in Beaverbrook's ministry, arranging accommodation for workers being redeployed around the country; sublet her home and moved into a cheap room on the top floor of The Dorchester (very risky during the Blitz). By accepting hospitality from others most evenings she was able to put her entire salary towards paying Randolph's debts. She may also have had a miscarriage at this time. The marriage was as good as over, and she soon began an affair with her future husband Averell Harriman, who was also staying at the Dorchester at the time.[84]

Once in Egypt, Randolph served as a General Staff (Intelligence) officer at Middle East HQ.[22] Averell Harriman visited Randolph in Cairo in June 1941 to bring him news of his family. Randolph, who himself had a long-term mistress and several casual girlfriends at the time, had no idea yet that he was being cuckolded. He had recently been reduced to tears on being told to his face by a brother officer how deeply disliked he was, something of which he had previously had no idea.[85] On 28 October 1941 he was promoted to the war-substantive rank of captain (acting rank of major) and put in charge of Army information at GHQ.[71][85] For a time he edited a newspaper, Desert News, for the troops.[80] He lived at Shepheard's Hotel. Anita Leslie, then in an ambulance company, wrote that "he could not cease trumpeting his opinions and older men could be seen turning purple with anger" and that he was "insufferable".[86]

On leave in January 1942, he criticised the Tories for exculpating Winston Churchill's decision to defend Greece and Crete. He was sensitive to the "co-operation and self-sacrifice" of parts of the Empire that in 1942 were in more immediate danger than the British Isles, mentioning Australia and Malaya which suffered under Japanese threats of invasion. He was scathing of Sir Herbert Williams' Official Report into the Conduct of the War.[87]

Loss of parliamentary seat[edit]

Randolph's attendance in the Commons was irregular and patchy, which may have contributed to his defeat in July 1945. He had assumed he would hold his seat in 1945, but did not (he never actually won a contested election to Parliament).[110]

Randolph had a blazing row with his father and Brendan Bracken at a dinner at Claridge's on 31 August.[111] The argument was about his father's planned war memoirs, and Randolph stalked off from the table as he disliked being spoken to abruptly by his father in public. His father had misunderstood him to be talking about getting the help of a literary agent, whereas Randolph was in fact urging his father to get tax advice from lawyers, as indeed he eventually did. Randolph had to write later that day explaining himself.[112]

Second marriage[edit]

Randolph was divorced from Pamela in 1946.[22] His sister writes that after the war he led a "rampaging existence" as "he always had lances to break, and hares to start". He was loyal and affectionate, but "would pick an argument with a chair".[113] Winston declared that he had a "deep animal love" for Randolph but that "every time we meet we seem to have a bloody row". Randolph believed that he could control his temper by willpower, but he could not do this when drunk and alcohol "fuelled his sense of thwarted destiny".[114] His father no longer had the energy for argument, so reduced the time he spent with Randolph and the amount he confided in him. Randolph maintained good written relations with his mother, but she could not stand arguments and often retreated to her room when he visited. She was able to help him out of his financial difficulties, which he acknowledged, "spared him much humiliation".[113]

As Winston Churchill's relations with his son cooled, he lavished affection on a series of surrogate sons, including Brendan Bracken and Randolph's brothers-in-law Duncan Sandys and, from 1947, Christopher Soames, as well as, to a certain extent, Anthony Eden. Randolph loathed all these men.[10] He had still not entirely abandoned his youthful fantasy of one day becoming Prime Minister, and resented Eden's position as his father's political heir.[115] Randolph used to refer to Eden as "Jerk Eden".[116]

Noël Coward quipped that Randolph was "utterly unspoiled by failure". He was blackballed from the Beefsteak Club and on one occasion was slapped twice across the face by Duff Cooper at the Paris Embassy for making an obnoxious remark. He reported on the Red Army parade from Moscow. He was still trying to persuade Laura Charteris to marry him. Although they were on–off lovers, she told friends that Randolph needed a mother rather than a wife.[115] In 1948 he tried to persuade Pamela to take him back, but she declined and, having converted to Catholicism, obtained a full annulment, soon beginning a relationship with Gianni Agnelli.[117] Randolph accepted that he could never have Laura, with whom he had been in love for much of his adult life.[118]

He courted June Osborne, his junior by eleven years. She was the daughter of Australia-born Colonel Rex Hamilton Osborne, D.S.O., M.C., of Little Ingleburn, Malmesbury, Wiltshire.[119][120][121][122] Mary Lovell describes her as "a vulnerable and needy girl-woman". They had a stormy three-month courtship, during which at one point June, high on a mixture of Benzedrine and wine, ran toward the River Thames and threatened suicide, calling the police and accusing Randolph of indecent assault when he tried to prevent her.[123] Evelyn Waugh wrote to Randolph (14 October 1948) that June "must be possessed of magnificent courage" to marry him. On 23 October he wrote to June at Randolph's request,[124] urging her to see Randolph's good side, calling him "a domestic and home-loving character who has never had a home".[123] Randolph and June were married in November 1948.[113][22]

Randolph's son Winston, then aged eight, remembered June as "a beautiful lady with long, blonde hair" who made an effort to bond with her young stepson.[125] Diana Cooper guessed at once after their honeymoon that Randolph and June were unsuited to one another. They had a daughter, Arabella (1949–2007).[123] The marriage soon deteriorated; his sister Mary later wrote that "He does not seem to have possessed the aptitudes for marriage".[113]

1960s[edit]

Natalie and relations with parents[edit]

In 1960 Randolph published the life of Edward Stanley, 17th Earl of Derby (described by Robert Blake as "a reputable if rather dull book" about a "dull man") to prove to the trustees of his father's papers that he was fit to write his official biography.[22] In May 1960 Sir Winston Churchill approved of Randolph's writing his life. "At last his life had found a purpose" his son later wrote.[166]

Natalie Bevan declined his proposal of marriage in August 1960, but by then they had settled into a stable relationship. Winston Churchill (the younger) never heard Randolph have a row with her.[158] Jonathan Aitken and Michael Wolff were eyewitnesses to Bobby Bevan bringing Natalie over for the evening and waiting patiently downstairs while she and Randolph enjoyed a Cinq à sept.[167] His divorce from his wife June became final in 1961.[113][22] The locals called him "the Beast of Bergholt" and he had a reputation for not paying small tradesmen. His researchers included Martin Gilbert, Michael Wolff, Franklin Gannon, Milo Cripps, Michael Molian, Martin Mauthner and Andrew Kerr.[168]

Jonathan Aitken first met him at Cherkley Court, the home of Aitken's great-uncle Lord Beaverbrook, where he was having a stand-up blazing row with the journalist Hugh Cudlipp who had made the mistake of criticising his father.[169] In the early 1960s, after they had spoken together at an Oxford Union debate the previous evening, Randolph invited Aitken to drive him back to London and join him for lunch with his parents at 28 Hyde Park Gate. After Randolph had insisted on stopping three times for drinks on the way, they arrived late and with Randolph smelling of drink. Aitken beat a hasty retreat as Randolph had a blazing row with his mother while Sir Winston, then in his late 80s, turned red, shook his legs and beat his walking sticks together with anger.[170]

Winston Churchill's secretary Anthony Montague Browne recorded an incident on board Aristotle Onassis's yacht in June 1963, in which Randolph "erupted like Stromboli", shouting abuse at his aged father, whom he accused of having connived for political reasons with his then wife's affair with Averell Harriman during the war, and calling a female diner who attempted to intervene "a gabby doll". Browne wrote that "[n]othing short of hitting him over the head with a bottle" would have stopped him. ... I had previously discounted the tales I had heard of Randolph. Now I believed them all." Sir Winston, too old to argue back, was physically shaking with rage, so that it was feared he might have another stroke, and afterwards made clear that he wanted his son off the boat. As he was taken off the next day (Onassis had got rid of him by arranging for him to interview the King of Greece) he was in tears, declaring his love for his father.[171]

Conservative leadership contest, 1963[edit]

Randolph often reported on American politics, and in Washington, DC he often stayed with his former fiancée Kay Halle, who was by then an important Washington hostess during the Democratic administrations of the 1960s. Parties with Washington insiders were often enlivened by his displays of what Aitken describes as Randolph's "boorish aggression and drunken bad manners". The American journalist Joseph Alsop stalked off from one conversation muttering that Randolph should entitle his memoirs "How to Lose Friends and Influence Nobody".[172]

In October 1963 he was in Washington (where he phoned through the news of Prime Minister Harold Macmillan's illness and impending resignation to President Kennedy). He flew home then travelled to Blackpool, where the Conservative Party Conference was in session. Randolph supported Lord Hailsham for the leadership rather than Macmillan's deputy Rab Butler. He knocked on the door of Butler's hotel room and urged him to withdraw from the contest, stressing the 60 telegrams which had been sent to him in support of Hailsham, many of them concocted by his team at East Bergholt. He distributed "Q" (for "Quintin", Lord Hailsham's first name) badges, pinning them on people; he tried to pin one on Lord Dilhorne's buttock without his noticing, but accidentally stabbed him with the pin, causing him to bellow with pain. After talking to Jonathan Aitken, who was working for Selwyn Lloyd at the time, he put £1,000 on the eventual winner Alec Douglas-Home at 6–1 to countervail his bet on Hailsham.[173] Maurice Macmillan, Julian Amery and others were heard to say of Randolph's antics on behalf of Hailsham "if anyone can balls it up, Randolph can".[174] He still hoped, somewhat unrealistically, for a peerage in Macmillan's resignation honours at the end of 1963.[175]

In 1964 Churchill published The Fight for the Party Leadership. The former Cabinet minister Iain Macleod wrote a review in The Spectator strongly critical of Randolph's book, and alleging that Macmillan had manipulated the process of "soundings" to ensure that Butler was not chosen as his successor.[176] Robert Blake wrote that Randolph was "blown out of the water" by Macleod's article (17 January 1964) and "for once ... had no comeback".[22]

Final years and biography of his father[edit]

In 1964 Randolph was laid low by bronchopneumonia which left him so frail he could only whisper. Later in the year he had a tumour, which turned out to be benign, removed from his lung.[177] His mother visited him frequently in hospital after his lung operation.[178] Randolph and Evelyn Waugh had barely spoken for 12 years,[179] but they restored friendly relations that spring; Waugh commented that "It was a typical triumph of modern science to find the one part of Randolph which was not malignant and to remove it."[180][g]

At his father's funeral in January 1965 Randolph walked for an hour in the intense cold, despite being not yet fully recovered from his lung operation.[183] After his father's death, Randolph's relations with his mother, whose approval he had always craved, mellowed a little.[184][185] Randolph organised a luncheon party for her 80th birthday at the Café Royal on 1 April 1965. She often sought and took his advice.[185] He wrote a memoir of his early life, Twenty-One Years, published in 1965.[164]

Winston Churchill's doctor Lord Moran published The Struggle for Survival in May 1966. Randolph wrote to The Times criticising him for publishing within 16 months of his patient's death and contrary to the wishes of the family.[186] Diana Mosley wrote to her sister Nancy Mitford that at least Moran had not told the truth about Churchill's children: "Randolph vile & making him cry" while Diana was being given electric shocks for hysteria and Sarah was frequently being arrested.[187]

Randolph never fully recovered from his 1964 operation.[187] By this time his health was in serious decline. He had been consuming 80–100 cigarettes and up to two bottles of whisky per day for 20 years, far in excess of his father's consumption.[188] Drink had long since destroyed his youthful good looks.[22][10] Accompanied by Natalie Bevan, he often spent winters in Marrakesh and summers in Monte Carlo, sometimes visiting Switzerland. His kidneys were failing, so he seldom drank alcohol any more, and ate little, becoming emaciated. Mary Lovell writes that "though he still behaved with the arrogance of Louis XIV he was less explosive". Natalie spent the days with him before returning to her own house after helping him to bed.[187]

In 1966 Randolph published the first volume of the official biography of his father.[187] He and his team of researchers carried on working on his father's biography despite his being mortally ill[189] and it brought him fulfilment which he had not previously known.[184] He had finished only the second volume and half a dozen companion volumes by the time of his death in 1968. Five volumes were planned (it eventually ran to eight, under the guidance of Sir Martin Gilbert).[187]

In 1966 he signed a contract with the American politician Robert F. Kennedy to write a biography of his elder brother, President John F. Kennedy, who had been assassinated in 1963.[173] As a consequence, Randolph obtained access to the Kennedy archives, but he died before beginning work, on the day that Robert was assassinated.[190]

Death[edit]

Randolph Churchill died of a heart attack during the night at his home, Stour House, East Bergholt, Suffolk and was found by one of his researchers the next morning,[187] 6 June 1968.[191] He was 57, and although he had been in poor health for years, his death was unexpected.[192]

He is buried with his parents (his mother outliving him by almost a decade) and all four of his siblings (Marigold was previously interred in Kensal Green Cemetery in London) at St Martin's Church, Bladon near Woodstock, Oxfordshire.[193] His will was valued for probate at £70,597 (equivalent to £1,302,545 in 2021).[194][22]

Media depiction[edit]

H.G. Wells in The Shape of Things to Come, published in 1934, predicted a Second World War in which Britain would not participate but would vainly try to effect a peaceful compromise. In this vision, Randolph was mentioned as one of several prominent Britons delivering "brilliant pacifist speeches [which] echo throughout Europe", but fail to end the war.[195]

Randolph Churchill was played by Nigel Havers in the Southern Television's 1981 drama series, Winston Churchill: The Wilderness Years, set in the decade Winston (played by Robert Hardy) was out of office and Randolph himself attempted to enter parliament.

In 2002, Randolph Churchill was portrayed by actor Tom Hiddleston in The Gathering Storm, the BBC – HBO co-produced television biographical film about Winston Churchill in the years just prior to World War II.

ITV TV docudrama Churchill's Secret, a screenplay based on the book The Churchill Secret: KBO by Jonathan Smith. Broadcast in 2016, it starred Michael Gambon, and depicted Winston Churchill during the summer of 1953 when he suffered a severe stroke, precipitating therapy and resignation; the character of Randolph was played by the English actor Matthew Macfadyen.

Jordan Waller portrayed Randolph Churchill in the 2017 war drama Darkest Hour.[196]

Ian Davies portrayed him in episode 5 of the 2022 TV series SAS: Rogue Heroes.