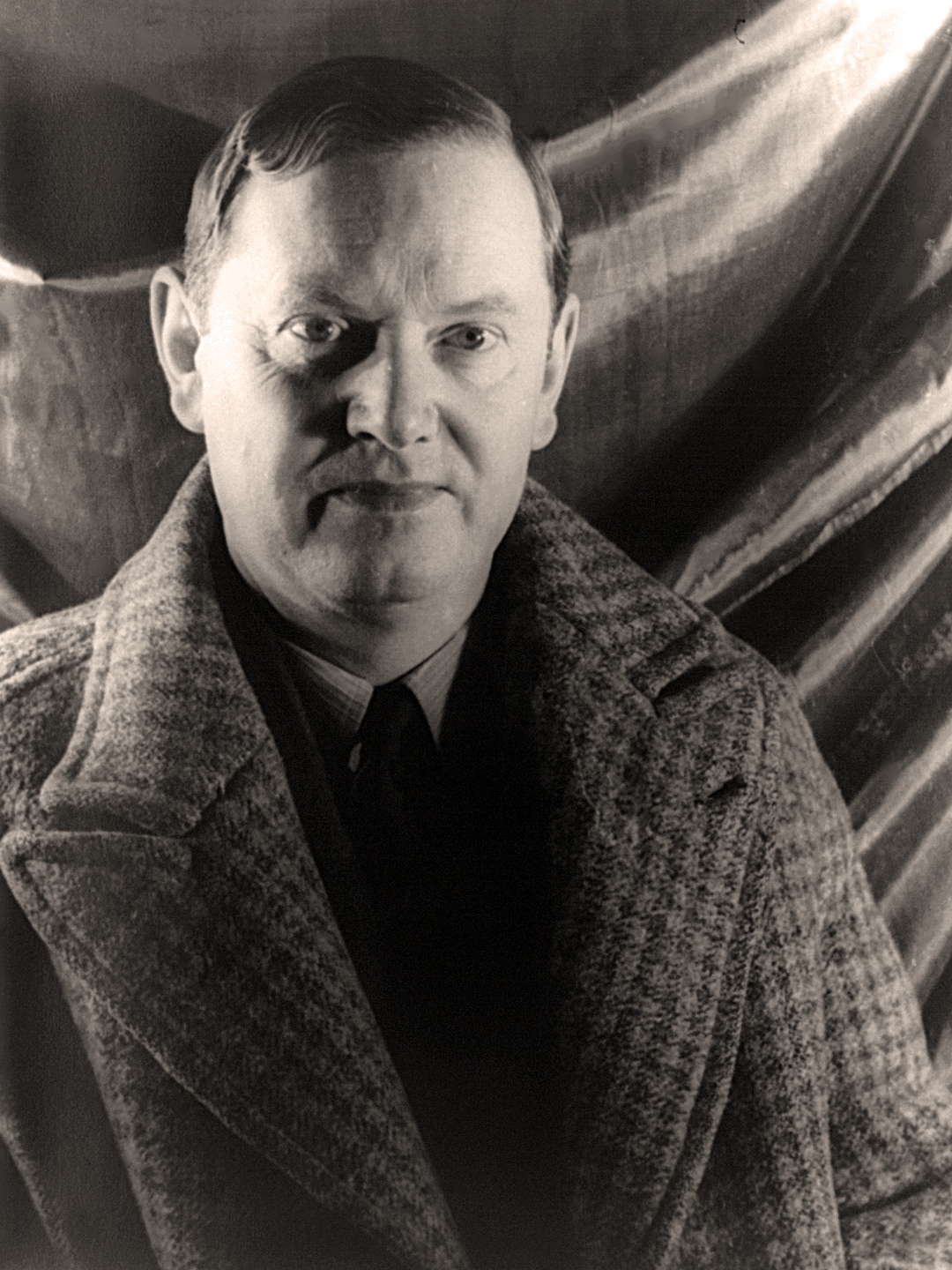

Evelyn Waugh

Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh (/ˈiːvlɪn ˈsɪndʒən ˈwɔː/; 28 October 1903 – 10 April 1966) was an English writer of novels, biographies, and travel books; he was also a prolific journalist and book reviewer. His most famous works include the early satires Decline and Fall (1928) and A Handful of Dust (1934), the novel Brideshead Revisited (1945), and the Second World War trilogy Sword of Honour (1952–1961). He is recognised as one of the great prose stylists of the English language in the 20th century.[1]

Evelyn Waugh

Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh

28 October 1903

West Hampstead, London, England

10 April 1966 (aged 62)

Combe Florey, Somerset, England

Writer

1923–1964

Novel, biography, short story, travelogue, autobiography, satire, humour

7, including Auberon Waugh

Waugh was the son of a publisher, educated at Lancing College and then at Hertford College, Oxford. He worked briefly as a schoolmaster before he became a full-time writer. As a young man, he acquired many fashionable and aristocratic friends and developed a taste for country house society.

He travelled extensively in the 1930s, often as a special newspaper correspondent; he reported from Abyssinia at the time of the 1935 Italian invasion. Waugh served in the British armed forces throughout the Second World War, first in the Royal Marines and then in the Royal Horse Guards. He was a perceptive writer who used the experiences and the wide range of people whom he encountered in his works of fiction, generally to humorous effect. Waugh's detachment was such that he fictionalised his own mental breakdown which occurred in the early 1950s.[2]

Waugh converted to Catholicism in 1930 after his first marriage failed. His traditionalist stance led him to strongly oppose all attempts to reform the Church, and the changes by the Second Vatican Council (1962–65) greatly disturbed his sensibilities, especially the introduction of the vernacular Mass. That blow to his religious traditionalism, his dislike for the welfare state culture of the postwar world, and the decline of his health all darkened his final years, but he continued to write. He displayed to the world a mask of indifference, but he was capable of great kindness to those whom he considered his friends. After his death in 1966, he acquired a following of new readers through the film and television versions of his works, such as the television serial Brideshead Revisited (1981).

Novelist and journalist[edit]

Recognition[edit]

Waugh's first biographer, Christopher Sykes, records that after the divorce friends "saw, or believed they saw, a new hardness and bitterness" in Waugh's outlook.[72] Nevertheless, despite a letter to Acton in which he wrote that he "did not know it was possible to be so miserable and live",[73] he soon resumed his professional and social life. He finished his second novel, Vile Bodies,[74] and wrote articles including (ironically, he thought) one for the Daily Mail on the meaning of the marriage ceremony.[73] During this period Waugh began the practice of staying at the various houses of his friends; he was to have no settled home for the next eight years.[74]

Vile Bodies, a satire on the Bright Young People of the 1920s, was published on 19 January 1930 and was Waugh's first major commercial success. Despite its quasi-biblical title, the book is dark, bitter, "a manifesto of disillusionment", according to biographer Martin Stannard.[75] As a best-selling author Waugh could now command larger fees for his journalism.[74] Amid regular work for The Graphic, Town and Country and Harper's Bazaar, he quickly wrote Labels, a detached account of his honeymoon cruise with She-Evelyn.[74]

Conversion to Catholicism[edit]

On 29 September 1930, Waugh was received into the Catholic Church. This shocked his family and surprised some of his friends, but he had contemplated the step for some time.[76] He had lost his Anglicanism at Lancing and had led an irreligious life at Oxford, but there are references in his diaries from the mid-1920s to religious discussion and regular churchgoing. On 22 December 1925, Waugh wrote: "Claud and I took Audrey to supper and sat up until 7 in the morning arguing about the Roman Church".[77] The entry for 20 February 1927 includes, "I am to visit a Father Underhill about being a parson".[78] Throughout the period, Waugh was influenced by his friend Olivia Plunket-Greene, who had converted in 1925 and of whom Waugh later wrote, "She bullied me into the Church".[79] It was she who led him to Father Martin D'Arcy, a Jesuit, who persuaded Waugh "on firm intellectual convictions but little emotion" that "the Christian revelation was genuine". In 1949, Waugh explained that his conversion followed his realisation that life was "unintelligible and unendurable without God".[80]

Second World War[edit]

Royal Marine and commando[edit]

Waugh left Piers Court on 1 September 1939, at the outbreak of the Second World War and moved his young family to Pixton Park in Somerset, the Herbert family's country seat, while he sought military employment.[108] He also began writing a novel in a new style, using first-person narration,[109] but abandoned work on it when he was commissioned into the Royal Marines in December and entered training at Chatham naval base.[110] He never completed the novel: fragments were eventually published as Work Suspended and Other Stories (1943).[111]

Waugh's daily training routine left him with "so stiff a spine that he found it painful even to pick up a pen".[112] In April 1940, he was temporarily promoted to captain and given command of a company of marines, but he proved an unpopular officer, being haughty and curt with his men.[113] Even after the German invasion of the Low Countries (10 May – 22 June 1940), his battalion was not called into action.[114] Waugh's inability to adapt to regimental life meant that he soon lost his command, and he became the battalion's Intelligence Officer. In that role, he finally saw action in Operation Menace as part of the British force sent to the Battle of Dakar in West Africa (23–25 September 1940) in August 1940 to support an attempt by the Free French Forces to overthrow the Vichy French colonial government and install General Charles de Gaulle. Operation Menace failed, hampered by fog and misinformation about the extent of the town's defences, and the British forces withdrew on 26 September. Waugh's comment on the affair was this: "Bloodshed has been avoided at the cost of honour."[115][116]

In November 1940, Waugh was posted to a commando unit, and, after further training, became a member of "Layforce", under Colonel (later Brigadier) Robert Laycock.[115] In February 1941, the unit sailed to the Mediterranean, where it participated in an unsuccessful attempt to recapture Bardia, on the Libyan coast.[117] In May, Layforce was required to assist in the evacuation of Crete: Waugh was shocked by the disorder and its loss of discipline and, as he saw it, the cowardice of the departing troops.[118] In July, during the roundabout journey home by troop ship, he wrote Put Out More Flags (1942), a novel of the war's early months in which he returned to the literary style he had used in the 1930s.[119] Back in Britain, more training and waiting followed until, in May 1942, he was transferred to the Royal Horse Guards, on Laycock's recommendation.[120] On 10 June 1942, Laura gave birth to Margaret, the couple's fourth child.[121][n 5]

Frustration, Brideshead and Yugoslavia[edit]

Waugh's elation at his transfer soon descended into disillusion as he failed to find opportunities for active service. The death of his father, on 26 June 1943, and the need to deal with family affairs prevented him from departing with his brigade for North Africa as part of Operation Husky (9 July – 17 August 1943), the Allied invasion of Sicily.[123] Despite his undoubted courage, his unmilitary and insubordinate character were rendering him effectively unemployable as a soldier.[124] After spells of idleness at the regimental depot in Windsor, Waugh began parachute training at Tatton Park, Cheshire, but landed awkwardly during an exercise and fractured a fibula. Recovering at Windsor, he applied for three months' unpaid leave to write the novel that had been forming in his mind. His request was granted and, on 31 January 1944, he departed for Chagford, Devon, where he could work in seclusion. The result was Brideshead Revisited: The Sacred & Profane Memories of Captain Charles Ryder (1945),[125] the first of his explicitly Catholic novels of which the biographer Douglas Lane Patey commented that it was "the book that seemed to confirm his new sense of his writerly vocation".[126]

Waugh managed to extend his leave until June 1944. Soon after his return to duty he was recruited by Randolph Churchill to serve in the Maclean Mission to Yugoslavia, and, early in July, flew with Churchill from Bari, Italy, to the Croatian island of Vis. There, they met Marshal Tito, the Communist leader of the Partisans, who was leading the guerrilla fight against the occupying Axis forces with Allied support.[127] Waugh and Churchill returned to Bari before flying back to Yugoslavia to begin their mission, but their aeroplane crash-landed, both men were injured, and their mission was delayed for a month.[128]

The mission eventually arrived at Topusko, where it established itself in a deserted farmhouse. The group's liaison duties, between the British Army and the Communist Partisans, were light. Waugh had little sympathy with the Communist-led Partisans and despised Tito. His chief interest became the welfare of the Catholic Church in Croatia, which, he believed, had suffered at the hands of the Serbian Orthodox Church and would fare worse when the Communists took control.[129] He expressed those thoughts in a long report, "Church and State in Liberated Croatia". After spells in Dubrovnik and Rome, Waugh returned to London on 15 March 1945 to present his report, which the Foreign Office suppressed to maintain good relations with Tito, now the leader of communist Yugoslavia.[130]

Postwar[edit]

Fame and fortune[edit]

Brideshead Revisited was published in London in May 1945.[131] Waugh had been convinced of the book's qualities, "my first novel rather than my last".[132] It was a tremendous success, bringing its author fame, fortune and literary status.[131] Happy though he was with this outcome, Waugh's principal concern as the war ended was the fate of the large populations of Eastern European Catholics, betrayed (as he saw it) into the hands of Stalin's Soviet Union by the Allies. He now saw little difference in morality between the war's combatants and later described it as "a sweaty tug-of-war between teams of indistinguishable louts".[133] Although he took momentary pleasure from the defeat of Winston Churchill and his Conservatives in the 1945 general election, he saw the accession to power of the Labour Party as a triumph of barbarism and the onset of a new "Dark Age".[131]

Works[edit]

Themes and style[edit]

Wykes observes that Waugh's novels reprise and fictionalise the principal events of his life, although in an early essay Waugh wrote: "Nothing is more insulting to a novelist than to assume that he is incapable of anything but the mere transcription of what he observes".[179] The reader should not assume that the author agreed with the opinions expressed by his fictional characters.[205] Nevertheless, in the Introduction to the Complete Short Stories, Ann Pasternak Slater said that the "delineation of social prejudices and the language in which they are expressed is part of Waugh's meticulous observation of his contemporary world".[206]

The critic Clive James said of Waugh: "Nobody ever wrote a more unaffectedly elegant English ... its hundreds of years of steady development culminate in him".[207] As his talent developed and matured, he maintained what literary critic Andrew Michael Roberts called "an exquisite sense of the ludicrous, and a fine aptitude for exposing false attitudes".[208] In the first stages of his 40-year writing career, before his conversion to Catholicism in 1930, Waugh was the novelist of the Bright Young People generation. His first two novels, Decline and Fall (1928) and Vile Bodies (1930), comically reflect a futile society, populated by two-dimensional, basically unbelievable characters in circumstances too fantastic to evoke the reader's emotions.[209] A typical Waugh trademark evident in the early novels is rapid, unattributed dialogue in which the participants can be readily identified.[206] At the same time Waugh was writing serious essays, such as "The War and the Younger Generation", in which he castigates his own generation as "crazy and sterile" people.[210]

Waugh's conversion to Catholicism did not noticeably change the nature of his next two novels, Black Mischief (1934) and A Handful of Dust (1934), but, in the latter novel, the elements of farce are subdued, and the protagonist, Tony Last, is recognisably a person rather than a comic cipher.[209] Waugh's first fiction with a Catholic theme was the short story "Out of Depth" (1933) about the immutability of the Mass.[211] From the mid-1930s onwards, Catholicism and conservative politics were much featured in his journalistic and non-fiction writing[212] before he reverted to his former manner with Scoop (1938), a novel about journalism, journalists, and unsavoury journalistic practices.[213]

In Work Suspended and Other Stories Waugh introduced "real" characters and a first-person narrator, signalling the literary style he would adopt in Brideshead Revisited a few years later.[214] Brideshead, which questions the meaning of human existence without God, is the first novel in which Evelyn Waugh clearly presents his conservative religious and political views.[26] In the Life magazine article "Fan Fare" (1946), Waugh said that "you can only leave God out [of fiction] by making your characters pure abstractions" and that his future novels shall be "the attempt to represent man more fully which, to me, means only one thing, man in his relation to God."[215] As such, the novel Helena (1950) is Evelyn Waugh's most philosophically Christian book.[216]

In Brideshead, the proletarian junior officer Hooper illustrates a theme that persists in Waugh's postwar fiction: the rise of mediocrity in the "Age of the Common Man".[26] In the trilogy Sword of Honour (Men at Arms, 1952; Officers and Gentlemen, 1955, Unconditional Surrender, 1961) the social pervasiveness of mediocrity is personified in the semi-comical character "Trimmer", a sloven and a fraud who triumphs by contrivance.[217] In the novella Scott-King's Modern Europe (1947), Waugh's pessimism about the future is in the schoolmaster's admonition: "I think it would be very wicked indeed to do anything to fit a boy for the modern world".[218] Likewise, such cynicism pervades the novel Love Among the Ruins (1953), set in a dystopian, welfare-state Britain that is so socially disagreeable that euthanasia is the most sought-after of the government's social services.[219] Of the postwar novels, Patey says that The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold (1957) stands out "a kind of mock-novel, a sly invitation to a game".[158] Waugh's final work of fiction, "Basil Seal Rides Again" (1962), features characters from the prewar novels; Waugh admitted that the work was a "senile attempt to recapture the manner of my youth".[220] Stylistically this final story begins in the same fashion as the first story, "The Balance" of 1926, with a "fusillade of unattributed dialogue".[206]

Reception[edit]

Of Waugh's early books, Decline and Fall was hailed by Arnold Bennett in the Evening Standard as "an uncompromising and brilliantly malicious satire".[221] The critical reception of Vile Bodies two years later was even more enthusiastic, with Rebecca West predicting that Waugh was "destined to be the dazzling figure of his age".[74] However, A Handful of Dust, later widely regarded as a masterpiece, received a more muted welcome from critics, despite the author's own high estimation of the work.[222] Chapter VI, "Du Côté de Chez Todd", of A Handful of Dust, with Tony Last condemned forever to read Dickens to his mad jungle captor, was thought by the critic Henry Yorke to reduce an otherwise believable book to "phantasy".[223] Cyril Connolly's first reaction to the book was that Waugh's powers were failing, an opinion that he later revised.[224]

In the latter 1930s, Waugh's inclination to Catholic and conservative polemics affected his standing with the general reading public.[26] The Campion biography is said by David Wykes to be "so rigidly biased that it has no claims to make as history".[225] The pro-fascist tone in parts of Waugh in Abyssinia offended readers and critics and prevented its publication in America.[226] There was general relief among critics when Scoop, in 1938, indicated a return to Waugh's earlier comic style. Critics had begun to think that his wit had been displaced by partisanship and propaganda.[213]

Waugh maintained his reputation in 1942, with Put Out More Flags, which sold well despite wartime restrictions on paper and printing.[227] Its public reception, however, did not compare with that accorded to Brideshead Revisited three years later, on both sides of the Atlantic. Brideshead's selection as the American Book of the Month swelled its US sales to an extent that dwarfed those in Britain, which was affected by paper shortages.[228] Despite the public's enthusiasm, critical opinion was split. Brideshead's Catholic standpoint offended some critics who had greeted Waugh's earlier novels with warm praise.[229] Its perceived snobbery and its deference to the aristocracy were attacked by, among others, Conor Cruise O'Brien who, in the Irish literary magazine The Bell, wrote of Waugh's "almost mystical veneration" for the upper classes.[230][231] Fellow writer Rose Macaulay believed that Waugh's genius had been adversely affected by the intrusion of his right-wing partisan alter ego and that he had lost his detachment: "In art so naturally ironic and detached as his, this is a serious loss".[232][233] Conversely, the book was praised by Yorke, Graham Greene and, in glowing terms, by Harold Acton who was particularly impressed by its evocation of 1920s Oxford.[234] In 1959, at the request of publishers Chapman and Hall and in some deference to his critics, Waugh revised the book and wrote in a preface: "I have modified the grosser passages but not obliterated them because they are an essential part of the book".[235]

In "Fan Fare", Waugh forecasts that his future books will be unpopular because of their religious theme.[215] On publication in 1950, Helena was received indifferently by the public and by critics, who disparaged the awkward mixing of 20th-century schoolgirl slang with otherwise reverential prose.[236] Otherwise, Waugh's prediction proved unfounded; all his fiction remained in print and sales stayed healthy. During his successful 1957 lawsuit against the Daily Express, Waugh's counsel produced figures showing total sales to that time of over four million books, two thirds in Britain and the rest in America.[237] Men at Arms, the first volume of his war trilogy, won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize in 1953;[238] initial critical comment was lukewarm, with Connolly likening Men at Arms to beer rather than champagne.[239] Connolly changed his view later, calling the completed trilogy "the finest novel to come out of the war".[240] Of Waugh's other major postwar works, the Knox biography was admired within Waugh's close circle but criticised by others in the Church for its depiction of Knox as an unappreciated victim of the Catholic hierarchy.[241] The book did not sell well—"like warm cakes", according to Waugh.[242] Pinfold surprised the critics by its originality. Its plainly autobiographical content, Hastings suggests, gave the public a fixed image of Waugh: "stout, splenetic, red-faced and reactionary, a figure from burlesque complete with cigar, bowler hat and loud checked suit".[243]

Reputation[edit]

In 1973, Waugh's diaries were serialised in The Observer prior to publication in book form in 1976. The revelations about his private life, thoughts and attitudes created controversy. Although Waugh had removed embarrassing entries relating to his Oxford years and his first marriage, there was sufficient left on the record to enable enemies to project a negative image of the writer as intolerant, snobbish and sadistic, with pronounced fascist leanings.[26] Some of this picture, it was maintained by Waugh's supporters, arose from poor editing of the diaries, and a desire to transform Waugh from a writer to a "character".[244] Nevertheless, a popular conception developed of Waugh as a monster.[245] When, in 1980, a selection of his letters was published, his reputation became the subject of further discussion. Philip Larkin, reviewing the collection in The Guardian, thought that it demonstrated Waugh's elitism; to receive a letter from him, it seemed, "one would have to have a nursery nickname and be a member of White's, a Roman Catholic, a high-born lady or an Old Etonian novelist".[246]