Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation and the European Reformation,[1] was a major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and the authority of the Catholic Church. Following the start of the Renaissance, the Reformation marked the beginning of Protestantism.

For other uses, see Reformation (disambiguation).

It is considered one of the events that signified the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the early modern period in Europe.[2] The end of the Reformation era is disputed among modern scholars.

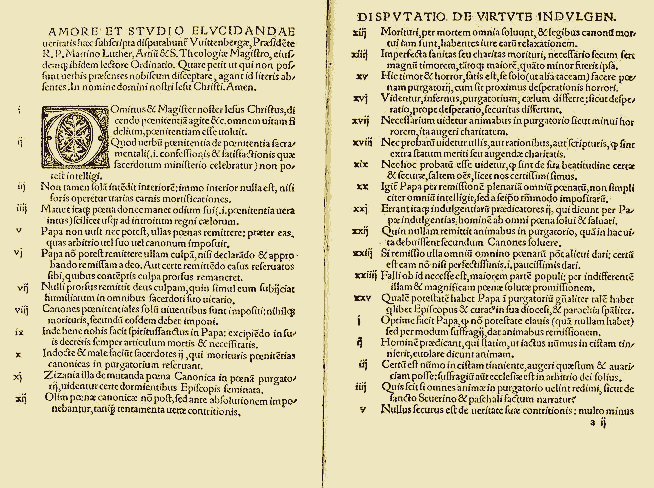

Prior to Martin Luther and other Protestant Reformers, there were earlier reform movements within Western Christianity. The Reformation, however, is usually considered to have started with the publication of the Ninety-five Theses, authored by Martin Luther in 1517. Four years later, in January 1521, Luther was excommunicated by Pope Leo X. In May 1521, at the Diet of Worms, Luther was condemned by the Holy Roman Empire, which officially banned citizens from defending or propagating Luther's ideas.[3] Luther survived after being declared an outlaw due to the protection of Elector Frederick the Wise.

The spread of Gutenberg's printing press provided the means for the rapid dissemination of religious materials in the vernacular. The initial movement in Germany diversified, and nearby other reformers such as Huldrych Zwingli and John Calvin with different theologies arose.

In general, the Reformers argued that salvation in Christianity was a completed status based on faith in Jesus alone and not a process that could involve good works, as in the Catholic view. Protestantism also introduced new ecclesiology.

The Counter-Reformation was the Catholic reform efforts initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation and its causes.[4]