Renewable Fuel Standard (United States)

The Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) is an American federal program that requires transportation fuel sold in the United States to contain a minimum volume of renewable fuels. It originated with the Energy Policy Act of 2005 and was expanded and extended by the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007. Research published by the Government Accountability Office in November 2016 found the program unlikely to meet its goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions due to limited current and expected future production of advanced biofuels.[1]

History[edit]

The RFS requires renewable fuel to be blended into transportation fuel in increasing amounts each year, escalating to 36 billion gallons by 2022. Each renewable fuel category in the RFS must emit lower levels of greenhouse gases relative to the petroleum fuel it replaces.[2]

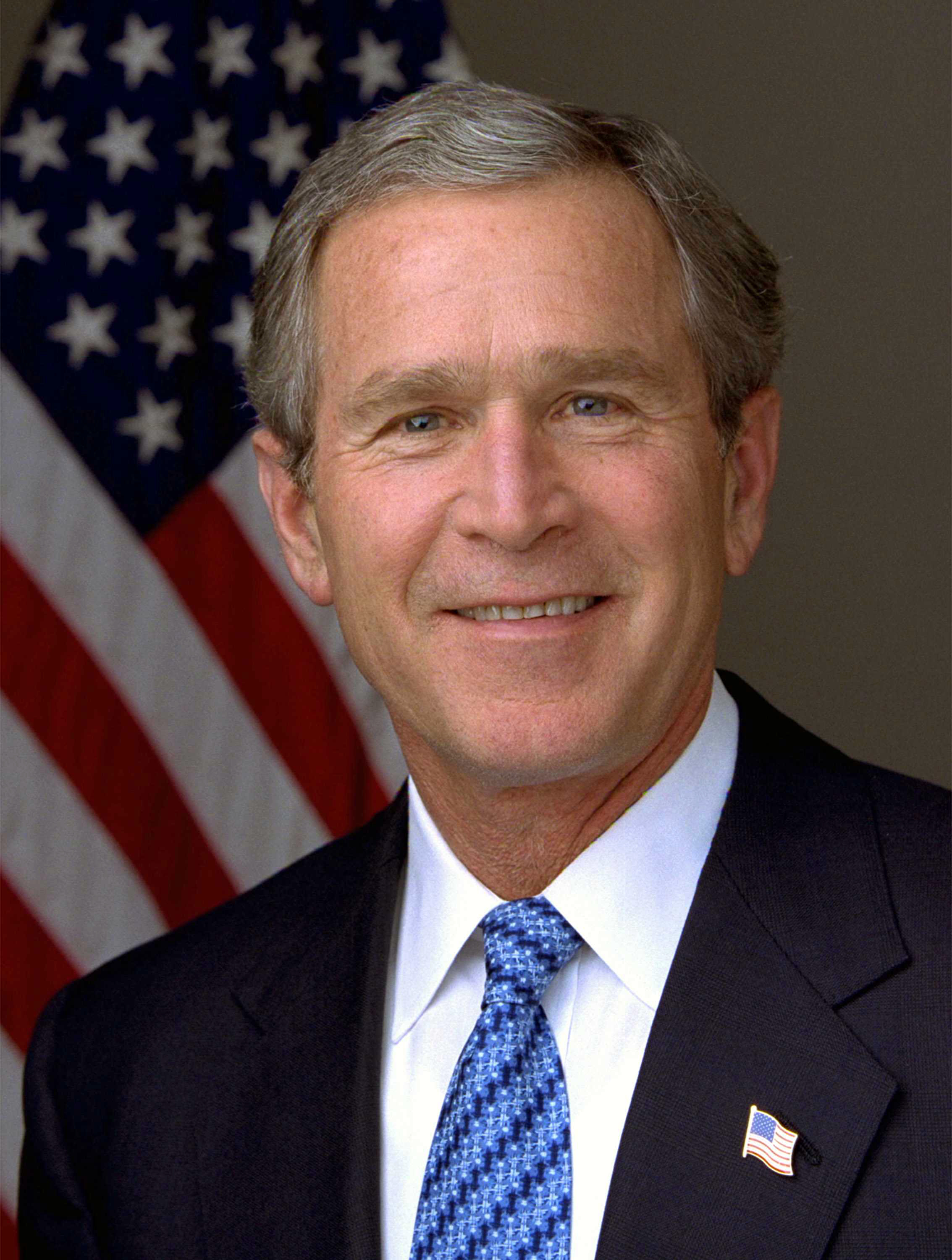

The first RFS, usually referred to as RFS1, required that 4 billion gallons of biofuel be used in 2006. This requirement was scheduled to rise to 7.5 billion gallons in 2012. These requirements were passed as part of the Energy Policy Act of 2005. The Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 changed and broadened these rules. EISA was signed into law by President George W. Bush and the bill was overwhelmingly supported by members of congress from both parties.[3]

The changes required by the 2007 legislation are usually referred to as RFS2. RFS2 required the use of 9 billion gallons in 2008 and scheduled a requirement for 36 billion gallons in 2022. The quota for 2022 was to allow no more than a maximum of 15 billion gallons from corn starch ethanol and a minimum of 16 billion gallons from cellulosic biofuels.[3]

In reaction to the implementation of the RFS, passage of EISA, and other measures to support ethanol, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) expressed alarm. In 2007, OPEC's secretary general, Abdalla El-Badri, said that increased use of biofuels by the United States could cause OPEC to decrease production. Other OPEC leaders openly worried about "security of demand."[4]

Effects[edit]

Food prices[edit]

According to research sponsored by the United States government, the World Bank, and other organizations, there is no clear link between the RFS and higher food prices. Ethanol critics contend that RFS requirements crowd out production that would go to feed livestock.[4][15]

The 2008 financial crisis illustrated corn ethanol's limited impact on corn prices, which fell 50% from their July 2008 high by October 2008, in tandem with other commodities, including oil, while corn ethanol production continued unabated. "Analysts, including some in the ethanol sector, say ethanol demand adds about 75 cents to $1.00 per bushel to the price of corn, as a rule of thumb. Other analysts say it adds around 20 percent, or just under 80 cents per bushel at current prices. Those estimates hint that $4 per bushel corn might be priced at only $3 without demand for ethanol fuel."[16]

University of Wisconsin researchers determined the RFS caused corn prices to be 30% higher and other crops 20% higher.[17]

Land use and emissions[edit]

A 2021 study from the University of Wisconsin found that the RFS increased corn cultivation by 8.7% and total cropland by 2.4% through 2016. This resulted in 3 to 8% more fertilizer use and 3 to 5% more release of water degradents. This land-use change resulted in corn ethanol's carbon intensity being no lower than gasoline's and up to 24% higher.[17]