Restraining order

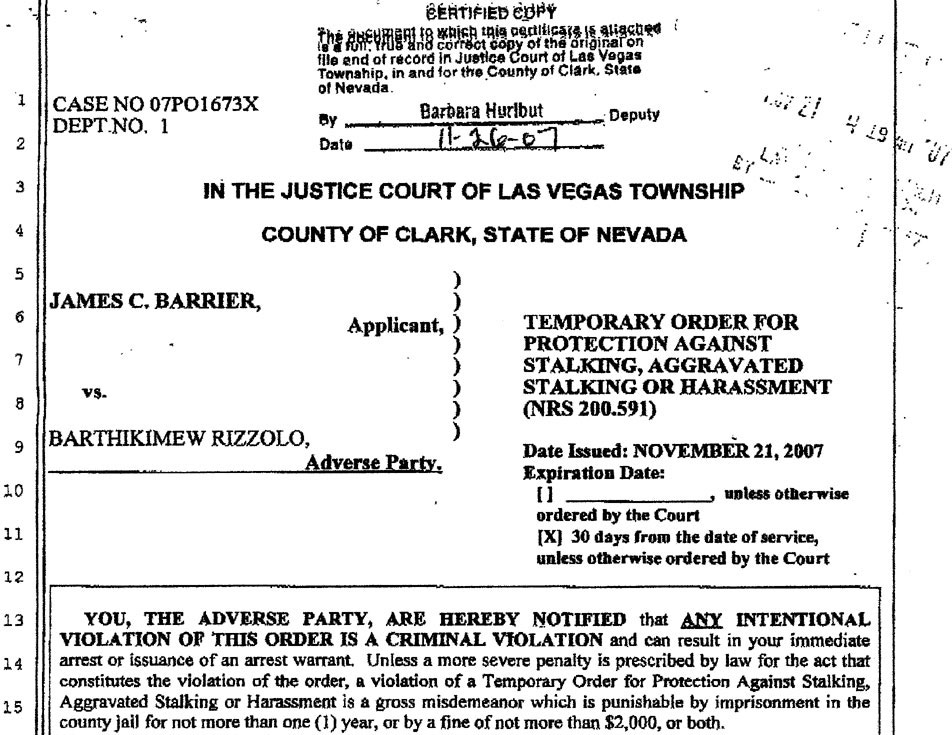

A restraining order or protective order,[a] is an order used by a court to protect a person in a situation often involving alleged domestic violence, child abuse, assault, harassment, stalking, or sexual assault.

Not to be confused with Restraint order, Civil restraint order, Temporary restraining order, or Protective order.Restraining and personal protection order laws vary from one jurisdiction to another but all establish who can file for an order, what protection or relief a person can get from such an order, and how the order will be enforced. The court will order the adverse party to refrain from certain actions or require compliance with certain provisions. Failure to comply is a violation of the order which can result in the arrest and prosecution of the offender. Violations in some jurisdictions may also constitute criminal or civil contempt of court.

Restraining order provisions[edit]

All protective order statutes permit the court to instruct an alleged abuser to stay a certain distance away from someone, such as their home, workplace or school ("stay away" provisions), and not to contact them. Alleged victims generally may also request the court to order that all contact, whether it be by telephone, notes, mail, fax, email, text, social media, or delivery of flowers, gifts, or drinks be prohibited ("no contact" provisions). Courts can also instruct an alleged abuser to not hurt or threaten someone ("cease abuse" provisions) known as no violent contact orders. The no-violent contact order statutes from the court may allow the alleged abuser to maintain their current living situation with the alleged victim or have contact with them.[3]

Some states also allow the court to order the alleged abuser to pay temporary support or continue to make mortgage payments on a home owned by both people ("support" provisions), to award sole use of a home or car owned by both people ("exclusive use" provisions), or to pay for medical costs or property damage caused by the alleged abuser ("restitution" provisions). Some courts might also be able to instruct the alleged abuser to turn over any firearms and ammunition they have ("relinquish firearms" provisions), attend a batterers' treatment program, appear for regular drug tests, or start alcohol or drug abuse counselling. Its issuance is sometimes called a "de facto divorce".[4]

Burden of proof and misuse[edit]

The standard of proof required to obtain a restraining order can vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, but it is generally lower than the standard of beyond a reasonable doubt required in criminal trials. Many US states—such as Oregon and Pennsylvania—use a standard of preponderance of the evidence. Other states use different standards, such as Wisconsin, which require that restraining orders be based on "reasonable grounds".[5]

Judges have some incentives to err on the side of granting restraining orders. If a judge grants a restraining order against someone who might not warrant it, typically the only repercussion is that the defendant might appeal the order. If, however, the judge denies a restraining order and the plaintiff is killed or injured, poor publicity and an enraged community reaction may harm the jurist's career.[4][6]

Colorado's statute inverts the standard court procedures and due process, providing that after the court issues an ex parte order, the defendant must "appear before the court at a specific time and date and . . . show cause, if any, why said temporary civil protection order should not be made permanent".[7] That is, Colorado courts place the burden of proof on the accused to establish his or her innocence, rather than requiring the accuser to prove his or her case. Hawaii similarly requires the defendant to prove his or her own innocence.[8]

The low burden of proof for restraining orders has led to some high-profile cases involving stalkers of celebrities obtaining restraining orders against their targets. For example, in 2005 a New Mexico judge issued a restraining order against New York City-based TV host David Letterman after a woman made claims of abuse and harassment, including allegations that Letterman had spoken to her via coded messages on his TV show. The judge later admitted that he granted the restraining order not on the merits of the case, but because the petitioner had completely filled out the required paperwork.[9]

Some attorneys have criticized the use of restraining orders on the theory that parties to a divorce may file such orders to gain tactical advantages, rather than out of a legitimate fear of harm. Liz Mandarano, an attorney who specializes in family and matrimonial law, speculates that divorce attorneys are incentivized to push for restraining orders because such orders force all communications to go through the parties' lawyers and may prolong the legal struggle.[10] Some attorneys offer to have restraining orders dropped in exchange for financial concessions in such proceedings.

Effectiveness[edit]

Experts disagree on whether restraining orders are effective in preventing further harassment. A 2010 analysis published in the Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law reviewed 15 U.S. studies of restraining order effectiveness, and concluded that restraining orders "can serve a useful role in threat management".[11] However, a 2002 analysis of 32 U.S. studies found that restraining orders are violated an average of 40 percent of the time and are perceived as being "followed by worse events" almost 21 percent of the time, and concluded that "evidence of [restraining orders'] relative efficacy is lacking", and that they may pose some degree of risk.[12] Other studies have found that restraining orders offer little or no assurance against future interpersonal violence.[13][14][15] A large America-wide telephone survey conducted in 1998 found that, of stalking victims who obtained a restraining order, only 30% of these orders kept the stalker away.

Threat management experts are often suspicious of restraining orders, believing they may escalate or enrage stalkers. In his 1997 book The Gift of Fear, American security specialist Gavin de Becker characterized restraining orders as "homework assignments police give to women to prove they're really committed to getting away from their pursuers," and said they "clearly serve police and prosecutors," but "they do not always serve victims". The Independent Women’s Forum decries them as "lulling women into a false sense of security," and in its Family Legal Guide, the American Bar Association warns “a court order might even add to the alleged offender's rage".[16]

Castle Rock v. Gonzales, 545 U.S. 748 (2005), is a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court ruled, 7–2, that a town and its police department could not be sued under for failing to enforce a restraining order, which had led to the murder of a woman's three children by her estranged husband.

Both parties must be informed of the restraining order for it to go into effect. Law enforcement may have trouble serving the order, making the petition unproductive. A study found that some counties had 91 percent of restraining orders non-served.[3] A temporary order of restraint ("ex parte" order) is in effect for two weeks before a court settles the terms of the order, but it is still not in effect until the alleged abuser is served.

Gender of parties[edit]

Restraining orders most commonly protect a woman against a male alleged abuser. A California study found that 72% of restraining orders active in the state at the time protected a woman against an alleged male abuser.[17] The Wisconsin Coalition Against Domestic Violence uses female pronouns to refer to petitioners and male pronouns to refer to abusers due to the fact that most petitioners are women and most alleged abusers are men.[18]