Rift

In geology, a rift is a linear zone where the lithosphere is being pulled apart[1][2] and is an example of extensional tectonics.[3] Typical rift features are a central linear downfaulted depression, called a graben, or more commonly a half-graben with normal faulting and rift-flank uplifts mainly on one side.[4] Where rifts remain above sea level they form a rift valley, which may be filled by water forming a rift lake. The axis of the rift area may contain volcanic rocks, and active volcanism is a part of many, but not all, active rift systems.

"Chasm" redirects here. For other uses, see Chasm (disambiguation).

Major rifts occur along the central axis of most mid-ocean ridges, where new oceanic crust and lithosphere is created along a divergent boundary between two tectonic plates.

Failed rifts are the result of continental rifting that failed to continue to the point of break-up. Typically the transition from rifting to spreading develops at a triple junction where three converging rifts meet over a hotspot. Two of these evolve to the point of seafloor spreading, while the third ultimately fails, becoming an aulacogen.

Rift development[edit]

Rift initiation[edit]

The formation of rift basins and strain localization reflects rift maturity. At the onset of rifting, the upper part of the lithosphere starts to extend on a series of initially unconnected normal faults, leading to the development of isolated basins.[8] In subaerial rifts, for example, drainage at the onset of rifting is generally internal, with no element of through drainage.

Mature rift stage[edit]

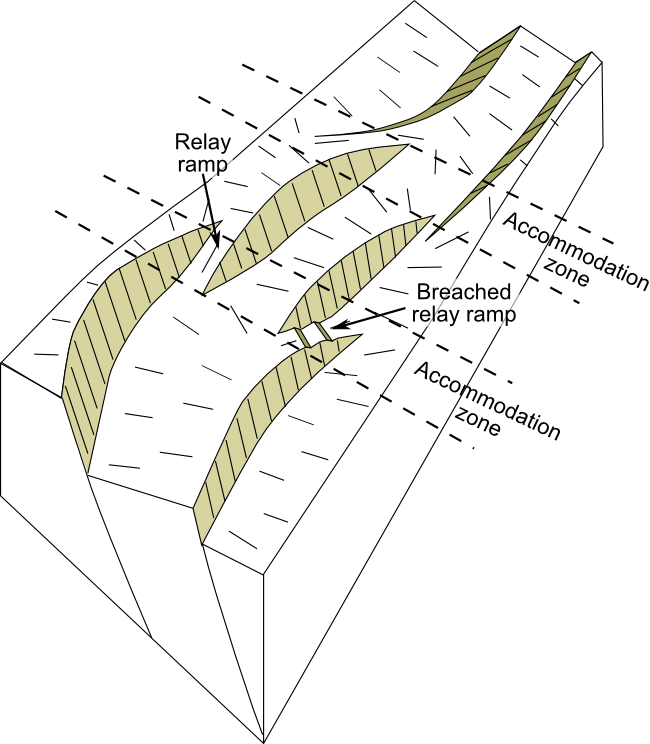

As the rift evolves, some of the individual fault segments grow, eventually becoming linked together to form the larger bounding faults. Subsequent extension becomes concentrated on these faults. The longer faults and wider fault spacing leads to more continuous areas of fault-related subsidence along the rift axis. Significant uplift of the rift shoulders develops at this stage, strongly influencing drainage and sedimentation in the rift basins.[8]

During the climax of lithospheric rifting, as the crust is thinned, the Earth's surface subsides and the Moho becomes correspondingly raised. At the same time, the mantle lithosphere becomes thinned, causing a rise of the top of the asthenosphere. This brings high heat flow from the upwelling asthenosphere into the thinning lithosphere, heating the orogenic lithosphere for dehydration melting, typically causing extreme metamorphism at high thermal gradients of greater than 30 °C. The metamorphic products are high to ultrahigh temperature granulites and their associated migmatite and granites in collisional orogens, with possible emplacement of metamorphic core complexes in continental rift zones but oceanic core complexes in spreading ridges. This leads to a kind of orogeneses in extensional settings, which is referred as to rifting orogeny.[9]

Post-rift subsidence[edit]

Once rifting ceases, the mantle beneath the rift cools and this is accompanied by a broad area of post-rift subsidence. The amount of subsidence is directly related to the amount of thinning during the rifting phase calculated as the beta factor (initial crustal thickness divided by final crustal thickness), but is also affected by the degree to which the rift basin is filled at each stage, due to the greater density of sediments in contrast to water. The simple 'McKenzie model' of rifting, which considers the rifting stage to be instantaneous, provides a good first order estimate of the amount of crustal thinning from observations of the amount of post-rift subsidence.[10][11] This has generally been replaced by the 'flexural cantilever model', which takes into account the geometry of the rift faults and the flexural isostasy of the upper part of the crust.[12]

Multiphase rifting[edit]

Some rifts show a complex and prolonged history of rifting, with several distinct phases. The North Sea rift shows evidence of several separate rift phases from the Permian through to the Earliest Cretaceous,[13] a period of over 100 million years.

Rifting to break-up[edit]

Rifting may lead to continental breakup and formation of oceanic basins. Successful rifting leads to seafloor spreading along a mid-oceanic ridge and a set of conjugate margins separated by an oceanic basin.[14] Rifting may be active, and controlled by mantle convection. It may also be passive, and driven by far-field tectonic forces that stretch the lithosphere. Margin architecture develops due to spatial and temporal relationships between extensional deformation phases. Margin segmentation eventually leads to the formation of rift domains with variations of the Moho topography, including proximal domain with fault-rotated crustal blocks, necking zone with thinning of crustal basement, distal domain with deep sag basins, ocean-continent transition and oceanic domain.[15]

Deformation and magmatism interact during rift evolution. Magma-rich and magma-poor rifted margins may be formed.[15] Magma-rich margins include major volcanic features. Globally, volcanic margins represent the majority of passive continental margins.[16] Magma-starved rifted margins are affected by large-scale faulting and crustal hyperextension.[17] As a consequence, upper mantle peridotites and gabbros are commonly exposed and serpentinized along extensional detachments at the seafloor.