Law of war

The law of war is a component of international law that regulates the conditions for initiating war (jus ad bellum) and the conduct of hostilities (jus in bello). Laws of war define sovereignty and nationhood, states and territories, occupation, and other critical terms of law.

"Laws of War" redirects here. For the Arma 3 expansion, see Arma 3 § Laws of War.

Among other issues, modern laws of war address the declarations of war, acceptance of surrender and the treatment of prisoners of war, military necessity, along with distinction and proportionality; and the prohibition of certain weapons that may cause unnecessary suffering.[1][2]

The law of war is considered distinct from other bodies of law—such as the domestic law of a particular belligerent to a conflict—which may provide additional legal limits to the conduct or justification of war.

The modern law of war is made up from three principal sources:[1]

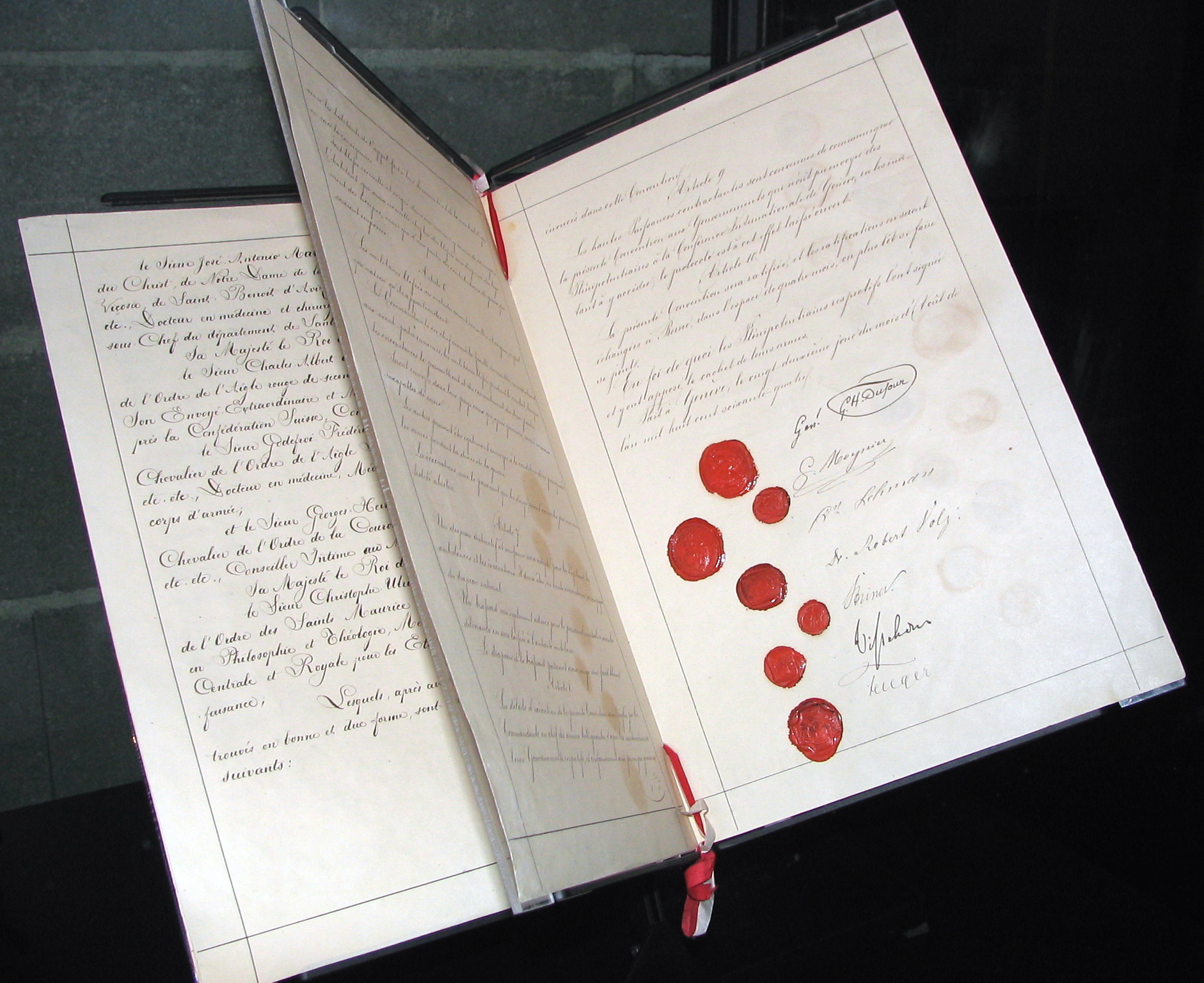

Positive international humanitarian law consists of treaties (international agreements) that directly affect the laws of war by binding consenting nations and achieving widespread consent.

The opposite of positive laws of war is customary laws of war,[1] many of which were explored at the Nuremberg War Trials. These laws define both the permissive rights of states as well as prohibitions on their conduct when dealing with irregular forces and non-signatories.

The Treaty of Armistice and Regularization of War signed on November 25 and 26, 1820 between the president of the Republic of Colombia, Simón Bolívar and the Chief of the Military Forces of the Spanish Kingdom, Pablo Morillo, is the precursor of the International Humanitarian Law.[7] The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed and ratified by the United States and Mexico in 1848, articulates rules for any future wars, including protection of civilians and treatment of prisoners of war.[8] The Lieber Code, promulgated by the Union during the American Civil War, was critical in the development of the laws of land warfare.[9]

Historian Geoffrey Best called the period from 1856 to 1909 the law of war's "epoch of highest repute."[10] The defining aspect of this period was the establishment, by states, of a positive legal or legislative foundation (i.e., written) superseding a regime based primarily on religion, chivalry, and customs.[11] It is during this "modern" era that the international conference became the forum for debate and agreement between states and the "multilateral treaty" served as the positive mechanism for codification.

The Nuremberg War Trial judgment on "The Law Relating to War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity"[12] held, under the guidelines Nuremberg Principles, that treaties like the Hague Convention of 1907, having been widely accepted by "all civilised nations" for about half a century, were by then part of the customary laws of war and binding on all parties whether the party was a signatory to the specific treaty or not.

Interpretations of international humanitarian law change over time and this also affects the laws of war. For example, Carla Del Ponte, the chief prosecutor for the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia pointed out in 2001 that although there is no specific treaty ban on the use of depleted uranium projectiles, there is a developing scientific debate and concern expressed regarding the effect of the use of such projectiles and it is possible that, in future, there may be a consensus view in international legal circles that use of such projectiles violates general principles of the law applicable to use of weapons in armed conflict.[13] This is because in the future it may be the consensus view that depleted uranium projectiles breach one or more of the following treaties: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Charter of the United Nations, the Genocide Convention, the United Nations Convention Against Torture, the Geneva Conventions including Protocol I, the Convention on Conventional Weapons of 1980, the Chemical Weapons Convention, and the Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material.[14]

It has often been commented that creating laws for something as inherently lawless as war seems like a lesson in absurdity. But based on the adherence to what amounted to customary international humanitarian law by warring parties through the ages, it was believed by many, especially after the eighteenth century, that codifying laws of war would be beneficial.[15]

Some of the central principles underlying laws of war are:

To this end, laws of war are intended to mitigate the hardships of war by:

The idea that there is a right to war concerns, on the one hand, the jus ad bellum, the right to make war or to enter war, assuming a motive such as to defend oneself from a threat or danger, presupposes a declaration of war that warns the adversary: war is a loyal act, and on the other hand, jus in bello, the law of war, the way of making war, which involves behaving as soldiers invested with a mission for which all violence is not allowed. In any case, the very idea of a right to war is based on an idea of war that can be defined as an armed conflict, limited in space, limited in time, and by its objectives. War begins with a declaration (of war), ends with a treaty (of peace) or surrender agreement, an act of sharing, etc.[16]

Applicability to states and individuals[edit]

The law of war is binding not only upon states as such but also upon individuals and, in particular, the members of their armed forces. Parties are bound by the laws of war to the extent that such compliance does not interfere with achieving legitimate military goals. For example, they are obliged to make every effort to avoid damaging people and property not involved in combat or the war effort, but they are not guilty of a war crime if a bomb mistakenly or incidentally hits a residential area.

By the same token, combatants that intentionally use protected people or property as human shields or camouflage are guilty of violations of the laws of war and are responsible for damage to those that should be protected.[26]

Remedies for violations[edit]

During conflict, punishment for violating the laws of war may consist of a specific, deliberate and limited violation of the laws of war in reprisal.

After a conflict ends, persons who have committed or ordered any breach of the laws of war, especially atrocities, may be held individually accountable for war crimes. Also, nations that signed the Geneva Conventions are required to search for, try and punish, anyone who had committed or ordered certain "grave breaches" of the laws of war. (Third Geneva Convention, Article 129 and Article 130.)

Combatants who break specific provisions of the laws of war are termed unlawful combatants. Unlawful combatants who have been captured may lose the status and protections that would otherwise be afforded to them as prisoners of war, but only after a "competent tribunal" has determined that they are not eligible for POW status (e.g., Third Geneva Convention, Article 5.) At that point, an unlawful combatant may be interrogated, tried, imprisoned, and even executed for their violation of the laws of war pursuant to the domestic law of their captor, but they are still entitled to certain additional protections, including that they be "treated with humanity and, in case of trial, shall not be deprived of the rights of fair and regular trial." (Fourth Geneva Convention Article 5.)