Samurai

Samurai (侍、さむらい) were the hereditary military nobility[1][2][3][4] and officer caste of medieval and early-modern Japan from the late 12th century until their abolition in the late 1870s during the Meiji era. They were the well-paid retainers of the daimyo, the great feudal landholders. They had high prestige and special privileges.[5]

For other uses, see Samurai (disambiguation).

Following the passing of a law in 1629, samurai on official duty were required to practice daishō (wear two swords).[6] Samurai were granted kiri-sute gomen: the right to kill anyone of a lower class in certain situations. Some important samurai and other figures in Japanese history wanted others to believe all of them engaged combatants using bushido codes of martial virtues and followed various cultural ideals about how a samurai should act.[7]

Although they had predecessors in earlier military and administrative officers, the samurai truly emerged during the Kamakura shogunate, ruling from c.1185 to 1333. They became the ruling political class, with significant power but also significant responsibility. During the 13th century, the samurai proved themselves as adept warriors against the invading Mongols. During the peaceful Edo period, 1603 to 1868, they became the stewards and chamberlains of the daimyo estates, gaining managerial experience and education.

In the 1870s, samurai families comprised 5% of the population. As modern militaries emerged in the 19th century, the samurai were rendered increasingly obsolete and very expensive to maintain compared to the average conscript soldier. The Meiji Restoration ended their feudal roles, and they moved into professional and entrepreneurial roles. Their memory and weaponry remain prominent in Japanese popular culture.

Terminology

In Japanese, historical warriors are usually referred to as bushi (武士, [bɯ.ɕi]), meaning 'warrior', or buke (武家), meaning 'military family'. According to translator William Scott Wilson: "In Chinese, the character 侍 was originally a verb meaning 'to wait upon', 'accompany persons' in the upper ranks of society, and this is also true of the original term in Japanese, saburau. In both countries the terms were nominalized to mean 'those who serve in close attendance to the nobility', the Japanese term saburai being the nominal form of the verb." According to Wilson, an early reference to the word saburai appears in the Kokin Wakashū, the first imperial anthology of poems, completed in the early 900s.[8]

In modern usage, bushi is often used as a synonym for samurai;[9][10][11] however, historical sources make it clear that bushi and samurai were distinct concepts, with the former referring to soldiers or warriors and the latter referring instead to a kind of hereditary nobility.[12][13] The word samurai is now closely associated with the middle and upper echelons of the warrior class. These warriors were usually associated with a clan and their lord, and were trained as officers in military tactics and grand strategy. While these samurai numbered less than 10% of then Japan's population,[14] their teachings can still be found today in both everyday life and in modern Japanese martial arts.

Philosophy

Religious influences

The philosophies of Confucianism,[62] Buddhism and Zen, and to a lesser extent Shinto, influenced the samurai culture. Zen meditation became an important teaching because it offered a process to calm one's mind. The Buddhist concept of reincarnation and rebirth led samurai to abandon torture and needless killing, while some samurai even gave up violence altogether and became Buddhist monks after coming to believe that their killings were fruitless. Some were killed as they came to terms with these conclusions in the battlefield. The most defining role that Confucianism played in samurai philosophy was to stress the importance of the lord-retainer relationship—the loyalty that a samurai was required to show his lord.

Literature on the subject of bushido such as Hagakure ("Hidden in Leaves") by Yamamoto Tsunetomo and Gorin no Sho ("Book of the Five Rings") by Miyamoto Musashi, both written in the Edo period, contributed to the development of bushidō and Zen philosophy.

According to Robert Sharf, "The notion that Zen is somehow related to Japanese culture in general, and bushidō in particular, is familiar to Western students of Zen through the writings of D. T. Suzuki, no doubt the single most important figure in the spread of Zen in the West."[87] In a 16th-century account of Japan sent to Father Ignatius Loyola at Rome, drawn from the statements of Anger (Han-Siro's western name), Xavier describes the importance of honor to the Japanese (Letter preserved at College of Coimbra):

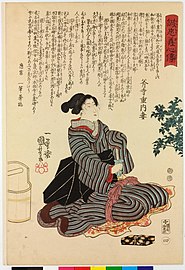

Maintaining the household was the main duty of women of the samurai class. This was especially crucial during early feudal Japan, when warrior husbands were often traveling abroad or engaged in clan battles. The wife, or okugatasama (meaning: one who remains in the home), was left to manage all household affairs, care for the children, and perhaps even defend the home forcibly. For this reason, many women of the samurai class were trained in wielding a polearm called a naginata or a special knife called the kaiken in an art called tantojutsu (lit. the skill of the knife), which they could use to protect their household, family, and honor if the need arose. There were women who actively engaged in battles alongside male samurai in Japan, although most of these female warriors were not formal samurai.[117]

A samurai's daughter's greatest duty was political marriage. These women married members of enemy clans of their families to form a diplomatic relationship. These alliances were stages for many intrigues, wars and tragedies throughout Japanese history. A woman could divorce her husband if he did not treat her well and also if he was a traitor to his wife's family. A famous case was that of Oda Tokuhime (daughter of Oda Nobunaga); irritated by the antics of her mother-in-law, Lady Tsukiyama (the wife of Tokugawa Ieyasu), she was able to get Lady Tsukiyama arrested on suspicion of communicating with the Takeda clan (then a great enemy of Nobunaga and the Oda clan). Ieyasu also arrested his own son, Matsudaira Nobuyasu, who was Tokuhime's husband, because Nobuyasu was close to his mother Lady Tsukiyama. To assuage his ally Nobunaga, Ieyasu had Lady Tsukiyama executed in 1579 and that same year ordered his son to commit seppuku to prevent him from seeking revenge for the death of his mother.

Traits valued in women of the samurai class were humility, obedience, self-control, strength, and loyalty. Ideally, a samurai wife would be skilled at managing property, keeping records, dealing with financial matters, educating the children (and perhaps servants as well), and caring for elderly parents or in-laws that may be living under her roof. Confucian law, which helped define personal relationships and the code of ethics of the warrior class, required that a woman show subservience to her husband, filial piety to her parents, and care to the children. Too much love and affection was also said to indulge and spoil the youngsters. Thus, a woman was also to exercise discipline.

Though women of wealthier samurai families enjoyed perks of their elevated position in society, such as avoiding the physical labor that those of lower classes often engaged in, they were still viewed as far beneath men. Women were prohibited from engaging in any political affairs and were usually not the heads of their household. This does not mean that women in the samurai class were always powerless. Powerful women both wisely and unwisely wielded power at various occasions. Throughout history, several women of the samurai class have acquired political power and influence, even though they have not received these privileges de jure.

After Ashikaga Yoshimasa, 8th shōgun of the Muromachi shogunate, lost interest in politics, his wife Hino Tomiko largely ruled in his place. Nene, wife of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, was known to overrule her husband's decisions at times, and Yodo-dono, his concubine, became the de facto master of Osaka castle and the Toyotomi clan after Hideyoshi's death. Tachibana Ginchiyo was chosen to lead the Tachibana clan after her father's death. Yamauchi Chiyo, wife of Yamauchi Kazutoyo, has long been considered the ideal samurai wife. According to legend, she made her kimono out of a quilted patchwork of bits of old cloth and saved pennies to buy her husband a magnificent horse, on which he rode to many victories. The fact that Chiyo (though she is better known as "Wife of Yamauchi Kazutoyo") is held in such high esteem for her economic sense is illuminating in the light of the fact that she never produced an heir and the Yamauchi clan was succeeded by Kazutoyo's younger brother. The source of power for women may have been that samurai left their finances to their wives. Several women ascended the Chrysanthemum Throne as a female imperial ruler (女性 天皇, josei tennō)

As the Tokugawa period progressed more value became placed on education, and the education of females beginning at a young age became important to families and society as a whole. Marriage criteria began to weigh intelligence and education as desirable attributes in a wife, right along with physical attractiveness. Though many of the texts written for women during the Tokugawa period only pertained to how a woman could become a successful wife and household manager, there were those that undertook the challenge of learning to read, and also tackled philosophical and literary classics. Nearly all women of the samurai class were literate by the end of the Tokugawa period.

As far back as the seventh century Japanese warriors wore a form of lamellar armor, which evolved into the armor worn by the samurai.[131] The first types of Japanese armor identified as samurai armor were known as ō-yoroi and dō-maru. These early samurai armors were made from small individual scales known as kozane. The kozane were made from either iron or leather and were bound together into small strips, and the strips were coated with lacquer to protect the kozane from water. A series of strips of kozane were then laced together with silk or leather lace and formed into a complete chest armor (dou or dō).[131] A complete set of the yoroi weighed 66 lbs.[132]

In the 16th century a new type of armor started to become popular after the advent of firearms, new fighting tactics by increasing the scale of battles and the need for additional protection and high productivity. The kozane dou, which was made of small individual scales, was replaced by itazane, which had larger iron plate or platy leather joined. Itazane can also be said to replace a row of individual kozanes with a single steel plate or platy leather. This new armor, which used itazane, was referred to as tosei-gusoku (gusoku), or modern armor.[55][133][134]

The gusoku armour added features and pieces of armor for the face, thigh, and back. The back piece had multiple uses, such as for a flag bearing.[135] The style of gusoku, like the plate armour, in which the front and back dou are made from a single iron plate with a raised center and a V-shaped bottom, was specifically called nanban dou gusoku (Western style gusoku).[55] Various other components of armor protected the samurai's body. The helmet (kabuto) was an important part of the samurai's armor. It was paired with a shikoro and fukigaeshi for protection of the head and neck.[136]

The garment worn under all of the armor and clothing was called the fundoshi, also known as a loincloth.[137] Samurai armor changed and developed as the methods of samurai warfare changed over the centuries.[138] The last known use of samurai armor occurring in 1877 during the Satsuma Rebellion.[139] As the last samurai rebellion was crushed, Japan modernized its defenses and turned to a national conscription army that used uniforms.[140]

Myth and reality

Most samurai were bound by a code of honor and were expected to set an example for those below them. A notable part of their code is seppuku (切腹, seppuku) or hara kiri, which allowed a disgraced samurai to regain his honor by passing into death, where samurai were still beholden to social rules. While there are many romanticized characterizations of samurai behavior such as the writing of Bushido: The Soul of Japan in 1899, studies of kobudō and traditional budō indicate that the samurai were as practical on the battlefield as were any other warriors.[157]

Some writers take issue with the very mention of the term bushido when not used to describe an individual samurai's usage of the word because of how broad and changed the meaning of it has become over time.[158]

Despite the rampant romanticism of the 20th century, samurai could be disloyal and treacherous (e.g., Akechi Mitsuhide), cowardly, brave, or overly loyal (e.g., Kusunoki Masashige). Samurai were usually loyal to their immediate superiors, who in turn allied themselves with higher lords. These loyalties to the higher lords often shifted; for example, the high lords allied under Toyotomi Hideyoshi were served by loyal samurai, but the feudal lords under them could shift their support to Tokugawa, taking their samurai with them. There were, however, also notable instances where samurai would be disloyal to their lord (daimyō), when loyalty to the emperor was seen to have supremacy.[159]