Sandro Botticelli

Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi (c. 1445[1] – May 17, 1510), better known as Sandro Botticelli (/ˌbɒtɪˈtʃɛli/ BOT-ih-CHEL-ee, Italian: [ˈsandro bottiˈtʃɛlli]) or simply Botticelli, was an Italian painter of the Early Renaissance. Botticelli's posthumous reputation suffered until the late 19th century, when he was rediscovered by the Pre-Raphaelites who stimulated a reappraisal of his work. Since then, his paintings have been seen to represent the linear grace of late Italian Gothic and some Early Renaissance painting, even though they date from the latter half of the Italian Renaissance period.

"Botticelli" redirects here. For other uses, see Botticelli (disambiguation).

Sandro Botticelli

Italian

Painting

In addition to the mythological subjects for which he is best known today, Botticelli painted a wide range of religious subjects (including dozens of renditions of the Madonna and Child, many in the round tondo shape) and also some portraits. His best-known works are The Birth of Venus and Primavera, both in the Uffizi in Florence, which holds many of Botticelli's works.[5] Botticelli lived all his life in the same neighbourhood of Florence; his only significant times elsewhere were the months he spent painting in Pisa in 1474 and the Sistine Chapel in Rome in 1481–82.[6]

Only one of Botticelli's paintings, the Mystic Nativity (National Gallery, London) is inscribed with a date (1501), but others can be dated with varying degrees of certainty on the basis of archival records, so the development of his style can be traced with some confidence. He was an independent master for all the 1470s, which saw his reputation soar. The 1480s were his most successful decade, the one in which his large mythological paintings were completed along with many of his most famous Madonnas. By the 1490s, his style became more personal and to some extent mannered. His last works show him moving in a direction opposite to that of Leonardo da Vinci (seven years his junior) and the new generation of painters creating the High Renaissance style, and instead returning to a style that many have described as more Gothic or "archaic".

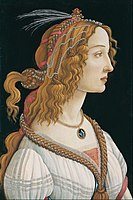

Botticelli painted a number of portraits, although not nearly as many as have been attributed to him. There are a number of idealized portrait-like paintings of women which probably do not represent a specific person (several closely resemble the Venus in his Venus and Mars).[76] Traditional gossip links these to the famous beauty Simonetta Vespucci, who died aged twenty-two in 1476, but this seems unlikely.[77] These figures represent a secular link to his Madonnas.

With one or two exceptions his small independent panel portraits show the sitter no further down the torso than about the bottom of the rib-cage. Women are normally in profile, full or just a little turned, whereas men are normally a "three-quarters" pose, but never quite seen completely frontally. Even when the head is facing more or less straight ahead, the lighting is used to create a difference between the sides of the face. Backgrounds may be plain, or show an open window, usually with nothing but sky visible through it. A few have developed landscape backgrounds. These characteristics were typical of Florentine portraits at the beginning of his career, but old-fashioned by his last years.[78]

Many portraits exist in several versions, probably most mainly by the workshop; there is often uncertainty in their attribution.[79] Often the background changes between versions while the figure remains the same. His male portraits have also often held dubious identifications, most often of various Medicis, for longer than the real evidence supports.[80] Lightbown attributes him only with about eight portraits of individuals, all but three from before about 1475.[81]

Botticelli often slightly exaggerates aspects of the features to increase the likeness.[82] He also painted portraits in other works, as when he inserted a self-portrait and the Medici into his early Adoration of the Magi.[83] Several figures in the Sistine Chapel frescos appear to be portraits, but the subjects are unknown, although fanciful guesses have been made.[84] Large allegorical frescos from a villa show members of the Tornabuoni family together with gods and personifications; probably not all of these survive but ones with portraits of a young man with the Seven Liberal Arts and a young woman with Venus and the Three Graces are now in the Louvre.[85]

Botticelli had a lifelong interest in the great Florentine poet Dante Alighieri, which produced works in several media.[88] He is attributed with an imagined portrait.[89] According to Vasari, he "wrote a commentary on a portion of Dante", which is also referred to dismissively in another story in the Life,[90] but no such text has survived.

Botticelli's attempt to design the illustrations for a printed book was unprecedented for a leading painter, and though it seems to have been something of a flop, this was a role for artists that had an important future.[91] Vasari wrote disapprovingly of the first printed Dante in 1481 with engravings by the goldsmith Baccio Baldini, engraved from drawings by Botticelli: "being of a sophistical turn of mind, he there wrote a commentary on a portion of Dante and illustrated the Inferno which he printed, spending much time over it, and this abstention from work led to serious disorders in his living."[92] Vasari, who lived when printmaking had become far more important than in Botticelli's day, never takes it seriously, perhaps because his own paintings did not sell well in reproduction.

The Divine Comedy consists of 100 cantos and the printed text left space for one engraving for each canto. However, only 19 illustrations were engraved, and most copies of the book have only the first two or three. The first two, and sometimes three, are usually printed on the book page, while the later ones are printed on separate sheets that are pasted into place. This suggests that the production of the engravings lagged behind the printing, and the later illustrations were pasted into the stock of printed and bound books, and perhaps sold to those who had already bought the book. Unfortunately Baldini was neither very experienced nor talented as an engraver, and was unable to express the delicacy of Botticelli's style in his plates.[93] Two religious engravings are also generally accepted to be after designs by Botticelli.[94]

Botticelli later began a luxury manuscript illustrated Dante on parchment, most of which was taken only as far as the underdrawings, and only a few pages are fully illuminated. This manuscript has 93 surviving pages (32 x 47 cm), now divided between the Vatican Library (8 sheets) and Berlin (83), and represents the bulk of Botticelli's surviving drawings.[95]

Once again, the project was never completed, even at the drawing stage, but some of the early cantos appear to have been at least drawn but are now missing. The pages that survive have always been greatly admired, and much discussed, as the project raises many questions. The general consensus is that most of the drawings are late; the main scribe can be identified as Niccolò Mangona, who worked in Florence between 1482 and 1503, whose work presumably preceded that of Dante. Botticelli then appears to have worked on the drawings over a long period, as stylistic development can be seen, and matched to his paintings. Although other patrons have been proposed (inevitably including Medicis, in particular the younger Lorenzo, or il Magnifico), some scholars think that Botticelli made the manuscript for himself.[96]

There are hints that Botticelli may have worked on illustrations for printed pamphlets by Savonarola, almost all destroyed after his fall.[97]

Other media[edit]

Vasari mentions that Botticelli produced very fine drawings, which were sought out by artists after his death.[125] Apart from the Dante illustrations, only a small number of these survive, none of which can be connected with surviving paintings, or at least not their final compositions, although they appear to be preparatory drawings rather than independent works. Some may be connected with the work in other media that we know Botticelli did. Three vestments survive with embroidered designs by him, and he developed a new technique for decorating banners for religious and secular processions, apparently in some kind of appliqué technique (called commesso).[126]

Personal life[edit]

Finances[edit]

According to Vasari's perhaps unreliable account, Botticelli "earned a great deal of money, but wasted it all through carelessness and lack of management".[122] He continued to live in the family house all his life, also having his studio there. On his father's death in 1482 it was inherited by his brother Giovanni, who had a large family. By the end of his life it was owned by his nephews. From the 1490s he had a modest country villa and farm at Bellosguardo (now swallowed up by the city), which was leased with his brother Simone.[132]

Sexuality[edit]

Botticelli never married, and apparently expressed a strong dislike of the idea of marriage. An anecdote records that his patron Tommaso Soderini, who died in 1485, suggested he marry, to which Botticelli replied that a few days before he had dreamed that he had married, woke up "struck with grief", and for the rest of the night walked the streets to avoid the dream resuming if he slept again. The story concludes cryptically that Soderini understood "that he was not fit ground for planting vines".[133]

He might have had a close relationship with Simonetta Vespucci (1453–1476), who has been claimed, especially by John Ruskin, to be portrayed in several of his works and to have served as the inspiration for many of the female figures in the artist's paintings. It is possible that he was at least platonically in love with Simonetta, given his request to have himself buried at the foot of her tomb in the Ognissanti – the church of the Vespucci – in Florence, although this was also Botticelli's church, where he had been baptized. When he died in 1510, his remains were placed as he requested.[134][135]

In 1938, Jacques Mesnil discovered a summary of a charge in the Florentine Archives for November 16, 1502, which read simply "Botticelli keeps a boy", an accusation of sodomy (homosexuality). No prosecution was brought. The painter would then have been about fifty-eight. Mesnil dismissed it as a customary slander by which partisans and adversaries of Savonarola abused each other. Opinion remains divided on whether this is evidence of homosexuality or not.[136] Many have backed Mesnil.[137] Art historian Scott Nethersole has suggested that a quarter of Florentine men were the subject of similar accusations, which "seems to have been a standard way of getting at people"[138] but others have cautioned against hasty dismissal of the charge.[139] Mesnil nevertheless concluded "woman was not the only object of his love".[140]

The Renaissance art historian, James Saslow, has noted that: "His [Botticelli's] homo-erotic sensibility surfaces mainly in religious works where he imbued such nude young saints as Sebastian with the same androgynous grace and implicit physicality as Donatello's David".[141]

After his death, Botticelli's reputation was eclipsed longer and more thoroughly than that of any other major European artist. His paintings remained in the churches and villas for which they had been created,[142] and his frescos in the Sistine Chapel were upstaged by those of Michelangelo.[143]

There are a few mentions of paintings and their location in sources from the decades after his death. Vasari's Life is relatively short and, especially in the first edition of 1550, rather disapproving. According to the Ettlingers "he is clearly ill at ease with Sandro and did not know how to fit him into his evolutionary scheme of the history of art running from Cimabue to Michelangelo".[144] Nonetheless, this is the main source of information about his life, even though Vasari twice mixes him up with Francesco Botticini, another Florentine painter of the day. Vasari saw Botticelli as a firm partisan of the anti-Medici faction influenced by Savonarola, while Vasari himself relied heavily on the patronage of the returned Medicis of his own day. Vasari also saw him as an artist who had abandoned his talent in his last years, which offended his high idea of the artistic vocation. He devotes a good part of his text to rather alarming anecdotes of practical jokes by Botticelli.[145] Vasari was born the year after Botticelli's death, but would have known many Florentines with memories of him.

In 1621 a picture-buying agent of Ferdinando Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua bought him a painting said to be a Botticelli out of historical interest "as from the hand of an artist by whom Your Highness has nothing, and who was the master of Leonardo da Vinci".[146] That mistake is perhaps understandable, as although Leonardo was only some six years younger than Botticelli, his style could seem to a Baroque judge to be a generation more advanced.

The Birth of Venus was displayed in the Uffizi from 1815, but is little mentioned in travellers' accounts of the gallery over the next two decades. The Berlin gallery bought the Bardi Altarpiece in 1829, but the National Gallery, London only bought a Madonna (now regarded as by his workshop) in 1855.[143]

The English collector William Young Ottley bought Botticelli's The Mystical Nativity in Italy, bringing it to London in 1799. But when he tried to sell it in 1811, no buyer could be found.[143] After Ottley's death, its next purchaser, William Fuller Maitland of Stansted, allowed it to be exhibited in a major art exhibition held in Manchester in 1857, the Art Treasures Exhibition,[147] where among many other art works it was viewed by more than a million people. His only large painting with a mythological subject ever to be sold on the open market is the Venus and Mars, bought at Christie's by the National Gallery for a rather modest £1,050 in 1874.[148] The rare 21st-century auction results include in 2013 the Rockefeller Madonna, sold at Christie's for US$10.4 million, and in 2021 the Portrait of a Young Man Holding a Roundel, sold at Sotheby's for US$92.2 million.[149]

The first nineteenth-century art historian to be enthusiastic about Botticelli's Sistine frescoes was Alexis-François Rio; Anna Brownell Jameson and Charles Eastlake were alerted to Botticelli as well, and works by his hand began to appear in German collections. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood incorporated elements of his work into their own.[150]

Walter Pater created a literary picture of Botticelli, who was then taken up by the Aesthetic movement. The first monograph on the artist was published in 1893, the same year as Aby Warburg's seminal dissertation on the mythologies; then, between 1900 and 1920 more books were written on Botticelli than on any other painter.[151] Herbert Horne's monograph in English from 1908 is still recognised as of exceptional quality and thoroughness,[152] "one of the most stupendous achievements in Renaissance studies".[153]

Botticelli appears as a character, sometimes a main one, in numerous fictional depictions of 15th-century Florence in various media. He was portrayed by Sebastian de Souza in the second season of the TV series Medici: Masters of Florence.[154]

The main belt asteroid 29361 Botticelli discovered on 9 February 1996, is named after him.[155]

![Giuliano de' Medici, who was assassinated in the Pazzi conspiracy. Several versions, all perhaps posthumous.[86]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/98/Giuliano_de%27_Medici_by_Sandro_Botticelli.jpeg/134px-Giuliano_de%27_Medici_by_Sandro_Botticelli.jpeg)

![Portrait of a Young Man c. 1480-1485.[87]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/45/Sandro_Botticelli_070.jpg/149px-Sandro_Botticelli_070.jpg)