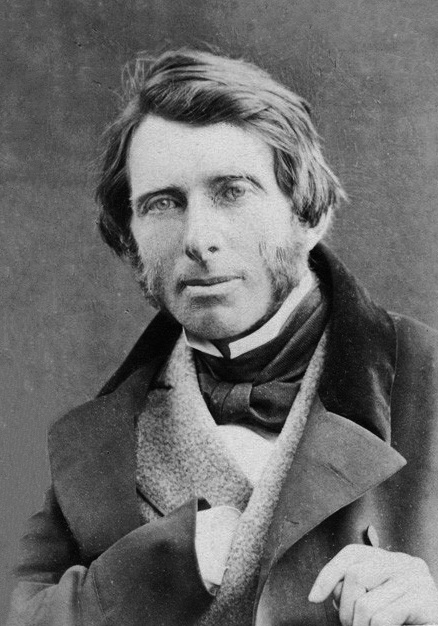

John Ruskin

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 – 20 January 1900) was an English writer, philosopher, art historian, art critic and polymath of the Victorian era. He wrote on subjects as varied as geology, architecture, myth, ornithology, literature, education, botany and political economy.

This article is about the art critic. For the painting by Millais, see John Ruskin (Millais). For the Canadian media personality, see Nardwuar.

John Ruskin

8 February 1819

20 January 1900 (aged 80)

- Modern Painters 5 vols. (1843–1860)

- The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849)

- The Stones of Venice 3 vols. (1851–1853)

- Unto This Last (1860, 1862)

- Fors Clavigera (1871–1884)

- Praeterita 3 vols. (1885–1889)

- Aesthetics

- ethics

- education

- political economy

Ruskin was heavily engaged by the work of Viollet-le-Duc which he taught to all his pupils including William Morris, notably Viollet-le-Duc's Dictionary, which he considered as "the only book of any value on architecture".[1] Ruskin's writing styles and literary forms were equally varied. He wrote essays and treatises, poetry and lectures, travel guides and manuals, letters and even a fairy tale. He also made detailed sketches and paintings of rocks, plants, birds, landscapes, architectural structures and ornamentation. The elaborate style that characterised his earliest writing on art gave way in time to plainer language designed to communicate his ideas more effectively. In all of his writing, he emphasised the connections between nature, art and society.

Ruskin was hugely influential in the latter half of the 19th century and up to the First World War. After a period of relative decline, his reputation has steadily improved since the 1960s with the publication of numerous academic studies of his work. Today, his ideas and concerns are widely recognised as having anticipated interest in environmentalism, sustainability and craft.

Ruskin first came to widespread attention with the first volume of Modern Painters (1843), an extended essay in defence of the work of J. M. W. Turner in which he argued that the principal role of the artist is "truth to nature". From the 1850s, he championed the Pre-Raphaelites, who were influenced by his ideas. His work increasingly focused on social and political issues. Unto This Last (1860, 1862) marked the shift in emphasis. In 1869, Ruskin became the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at the University of Oxford, where he established the Ruskin School of Drawing. In 1871, he began his monthly "letters to the workmen and labourers of Great Britain", published under the title Fors Clavigera (1871–1884). In the course of this complex and deeply personal work, he developed the principles underlying his ideal society. As a result, he founded the Guild of St George, an organisation that endures today.

Early life (1819–1846)[edit]

Genealogy[edit]

Ruskin was the only child of first cousins.[2] His father, John James Ruskin (1785–1864), was a sherry and wine importer,[2] founding partner and de facto business manager of Ruskin, Telford and Domecq (see Allied Domecq). John James was born and brought up in Edinburgh, Scotland, to a mother from Glenluce and a father originally from Hertfordshire.[2][3] His wife, Margaret Cock (1781–1871), was the daughter of a publican in Croydon.[2] She had joined the Ruskin household when she became companion to John James's mother, Catherine.[2]

John James had hoped to practise law, and was articled as a clerk in London.[2] His father, John Thomas Ruskin, described as a grocer (but apparently an ambitious wholesale merchant), was an incompetent businessman. To save the family from bankruptcy, John James, whose prudence and success were in stark contrast to his father, took on all debts, settling the last of them in 1832.[2] John James and Margaret were engaged in 1809, but opposition to the union from John Thomas, and the problem of his debts, delayed the couple's wedding. They finally married, without celebration, in 1818.[4] John James died on 3 March 1864 and is buried in the churchyard of St John the Evangelist, Shirley, Croydon.

Controversies[edit]

Turner's erotic drawings[edit]

Until 2005, biographies of both J. M. W. Turner and Ruskin had claimed that in 1858 Ruskin burned bundles of erotic paintings and drawings by Turner to protect Turner's posthumous reputation. Ruskin's friend Ralph Nicholson Wornum, who was Keeper of the National Gallery, was said to have colluded in the alleged destruction of Turner's works. In 2005, these works, which form part of the Turner Bequest held at Tate Britain, were re-appraised by Turner Curator Ian Warrell, who concluded that Ruskin and Wornum had not destroyed them.[235][236]

Sexuality[edit]

Ruskin's sexuality has been the subject of a great deal of speculation. He was married once, to Effie Gray, whom he met when she was 12 and he was 21, and Gray's family encouraged a match between the two when she had matured. The marriage was annulled after six years owing to non-consummation. Effie, in a letter to her parents, claimed that Ruskin found her "person" repugnant:

The OED credits Ruskin with the first quotation in 152 separate entries. Some include: