South Thailand insurgency

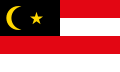

The South Thailand insurgency (Thai: ความไม่สงบในชายแดนภาคใต้ของประเทศไทย; Malay: Pemberontakan di Selatan Thailand) is an ongoing conflict centered in southern Thailand. It originated in 1948[58] as an ethnic and religious separatist insurgency in the historical Malay Patani Region, made up of the three southernmost provinces of Thailand and parts of a fourth, but has become more complex and increasingly violent since the early 2000s from drug cartels,[59][60] oil smuggling networks,[31][61] and sometimes pirate raids.[62][63]

The former Sultanate of Pattani, which included the southern Thai provinces of Pattani (Patani), Yala (Jala), Narathiwat (Menara)—also known as the three Southern Border Provinces (SBP)[64]—as well as neighbouring parts of Songkhla Province (Singgora), and the northeastern part of Malaysia (Kelantan), was conquered by the Kingdom of Siam in 1785 and, except for Kelantan, has been governed by Thailand ever since.

Although low-level separatist violence had occurred in the region for decades, the campaign escalated after 2001, with a recrudescence in 2004, and has occasionally spilled over into other provinces.[65] Incidents blamed on southern insurgents have occurred in Bangkok and Phuket.[66]

In July 2005, Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra assumed wide-ranging emergency powers to deal with the southern violence, but the insurgency escalated further. On 19 September 2006, a military junta ousted Thaksin Shinawatra in a coup. The junta implemented a major policy shift by replacing Thaksin's earlier approach with a campaign to win over the "hearts and minds" of the insurgents.[67] Despite little progress in curbing the violence, the junta declared that security was improving and that peace would come to the region by 2008.[68] By March 2008, however, the death toll surpassed 3,000.[69]

During the Democrat-led government of Abhisit Vejjajiva, Foreign Minister Kasit Piromya noted a "sense of optimism" and said that he was confident of bringing peace to the region in 2010.[70] But by the end of 2010 insurgency-related violence had increased, confounding the government's optimism.[71] Finally in March 2011, the government conceded that violence was increasing and could not be solved in a few months.[72]

Local leaders have persistently demanded at least a level of autonomy from Thailand for the Patani region and some of the separatist insurgent movements have made a series of prior demands before engaging in peace talks and negotiations. However, these groups have been largely sidelined by the Barisan Revolusi Nasional-Koordinasi (BRN-C), the group currently spearheading the insurgency. It sees no reason for negotiations and is against talks with other insurgent groups. The BRN-C has as its immediate aim to make southern Thailand ungovernable and it has largely been successful.[73]

Estimates of the strength of the insurgency vary greatly. In 2004, General Pallop Pinmanee claimed that there were only 500 hardcore jihadists. Other estimates say there as many as 15,000 armed insurgents. Around 2004, some Thai analysts believed that foreign Islamic terrorist groups were infiltrating the area, and that foreign funds and arms were being brought in, though again, such claims were balanced by an equally large body of opinion suggesting this remains a distinctly local conflict.

Over 6,500 people died and almost 12,000 were injured between 2004 and 2015 in a formerly ethnic separatist insurgency, which has currently been taken over by hard-line jihadis and pitted them against both the Thai-speaking Buddhist minority and local Muslims who have a moderate approach or who support the Thai government.[55]

Reactions and explanations[edit]

Official reactions[edit]

The government at first blamed the attacks on "bandits", and many outside observers believe that local clan, commercial or criminal rivalries played a role in the violence.

In 2002, Thaksin stated, "There's no separatism, no ideological terrorists, just common bandits." By 2004, however, he had reversed his position and had come to regard the insurgency as a local front in the global war on terrorism. Martial law was instituted in Pattani, Yala, and Narathiwat in January 2004.[91]

Since the 2006 military coup, the Thai government has taken a more conciliatory approach to the insurgency, avoiding the excessive use of force that typified Thaksin's time in office, and opened negotiations with known separatist groups. Violence, however, has escalated. This likely backs the assertion that there are several groups involved in the violence, few of whom have been placated by the government's change of strategy.[92]

On 3 June 2011, Army Chief Prayut Chan-o-cha stated that the insurgency is orchestrated from abroad and funded via drug and oil smuggling.[93]

Islam[edit]

Although Thailand's southern violence is mostly ethnic-based, anonymous leaflets issued by militant groups often contain jihadist language. Many young militants received training and indoctrination from Islamic teachers, some of which took place within Islamic educational institutions. Many see the southern Thai violence as a form of Islamist militancy and Islamic separatism, testifying to the strength of Malay Muslim beliefs and the determination of local people to resist the (Buddhist) Thai state on religious grounds.[94]

Recently, a religious factor has been brought to discussion due to the rise of the Islamist movement, especially the Salafi movement, which aimed to liberate the Muslim-dominated Malay regions from Thailand.[95]

Political factors[edit]

Thai authorities claim that the insurgency is not caused by a lack of political representation of the Muslim population. By the late 1990s, Muslims were holding unprecedented senior posts in Thai politics. For example, Wan Muhamad Noor Matha, a Malay Muslim from Yala, served as chairman of parliament from 1996 to 2001 under the Democrats and later as interior minister during the first Thaksin government. Thaksin's first government (2001–2005) also saw 14 Muslim members of parliament (MPs) and several Muslim senators. Muslims dominated provincial legislative assemblies in the border provinces, and several southern municipalities had Muslim mayors. Muslims were able to voice their political grievances openly and enjoy a much greater degree of religious freedom.

The Thaksin regime, however, began to dismantle the southern administration organisation, replacing it with a notoriously corrupt police force that immediately began widespread crackdowns. Consultation with local community leaders was also abolished. Discontent over the abuses led to growing violence during 2004 and 2005. Muslim politicians and leaders remained silent out of fear of repression, thus eroding their political legitimacy and support. This cost them dearly. In the 2005 general election, all but one of the eleven incumbent Muslim MPs who stood for election were voted out of office.[96]

Economic factors[edit]

Poverty and economic problems are a key factor behind the insurgency.[97][98]

Although Thailand's economy has grown dramatically in the past several decades, gains in both northern and southern provinces have been relatively limited.[99] Income differences between Buddhist and Muslim households are especially pronounced in the border region.[100]

The percentage of people living below the poverty line also fell, from 40%, 36%, and 33% in 2000 to 18%, 10%, and 23% in 2004 for Pattani, Narathiwat, and Yala, respectively. By 2004, the three provinces had 310,000 people living below the poverty line, compared to 610,000 in 2000. However, 45% of all poor southerners lived in the three border provinces.[101][102]

Muslims in the border provinces generally have lower levels of educational attainment compared to their Buddhist neighbours. 69.80% of the Muslim population in the border provinces have only a primary school education, compared to 49.6% of Buddhists in the same provinces. Only 9.20% of Muslims have completed secondary education (including those who graduated from private Islamic schools), compared to 13.20% of Buddhists. Just 1.70% of the Muslim population have a bachelor's degree, while 9.70% of Buddhists hold undergraduate degrees. Government schools generally enforce a Thai language curriculum to the exclusion of the region's Patani-Malay languages, a policy which produces low literacy rates and contributes to the view of government schools as antagonistic to Malay culture.[103][104] The secular educational system is being undermined by the destruction of schools and the murders of teachers by the insurgent groups.[105]

The lesser educated Muslims also have reduced employment opportunities compared to their Buddhist neighbours. Only 2.4% of all working Muslims in the provinces held government posts, compared with 19.2% of all working Buddhists. Jobs in the Thai public sector are difficult to obtain for those Muslims who never fully accepted the Thai language or the Thai education system. Insurgent attacks on economic targets further reduce employment opportunities for both Muslims and Buddhists in the provinces.

High profile incidents[edit]

Krue Se Mosque Incident[edit]

On 28 April 2004, more than 100 militants carried out terrorist attacks against 10 police outposts across Pattani, Yala, and Songkhla Provinces in south Thailand.[112] Thirty-two gunmen retreated to the 16th-century Krue Se Mosque, regarded by Muslims as the holiest mosque in Pattani.

General Pallop Pinmanee, commander of the "Southern Peace Enhancement Center" and deputy director of the Internal Security Operations Command, was the senior army officer on the scene. After a tense seven-hour stand-off, Pallop ordered an all-out assault on the mosque. All of the gunmen were killed. He later insisted, "I had no choice. I was afraid that as time passed the crowd would be sympathetic to the insurgents, to the point of trying to rescue them".[113]

It was later revealed that Pallop's order to storm the mosque contravened a direct order by Defense Minister Chavalit Yongchaiyudh to seek a peaceful resolution to the stand-off no matter how long it took.[114] Pallop was immediately ordered out of the area, and later tendered his resignation as commander of the Southern Peace Enhancement Center. The forward command of the Internal Security Operations Command (ISOC), which Pallop headed, was also dissolved. A government investigative commission found that the security forces had over-reacted. The Asian Centre for Human Rights questioned the independence and impartiality of the investigative commission. On 3 May 2004 during a senate hearing, Senator Kraisak Choonhavan noted that most of those killed at Krue Se Mosque had been shot in the head and there were signs that ropes had been tied around their wrists, suggesting they had been executed after being captured.

The incident resulted in a personal conflict between Pallop and Defense Minister Chavalit, who was also director of the ISOC.[115] Pallop later demanded that the defence minister cease any involvement in the management of the southern insurgency.[116]

Reconciliation and negotiation[edit]

Negotiation attempts[edit]

Attempts to negotiate with insurgents were hampered by the anonymity of the insurgency's leaders.

In May 2004, Wan Kadir Che Man, exiled leader of Bersatu and for years one of the key symbolic figures in the guerrilla movement, stated that he would be willing to negotiate with the government to end the southern violence. He also hinted that Bersatu would be willing to soften its previous demands for an independent state.[128][129]

The government initially welcomed the request to negotiate. However, the government response was severely criticised as being "knee-jerk" and "just looking to score cheap political points."[129] But when it became apparent that, despite his softened demand for limited autonomy, Wan Kadir Che Man had no influence over the violence, the negotiations were cancelled.[129] The government then began a policy of not attempting to officially negotiate with the insurgents.[130]

After being appointed army commander in 2005, General Sonthi Boonyaratglin expressed confidence that he could resolve the insurgency. He claimed that he would take a "new and effective" approach to a crisis and that "The Army is informed [of who the insurgents are] and will carry out their duties."[131]

On 1 September 2006, a day after 22 commercial banks were simultaneously bombed in Yala Province, Sonthi announced that he would break with the government's no-negotiation policy. However, he noted that "We still don't know who is the real head of the militants we are fighting with."[132] In a press conference the next day, he attacked the government for criticising him for trying to negotiate with the anonymous insurgents, and demanded that the government "Free the military and let it do the job."[133] His confrontation with the government made his call for negotiation extremely popular with the media.[130] Afterwards, insurgents bombed six department stores in Hat Yai city, which until then had been free of insurgent activities. The identity of the insurgents was not revealed. Sonthi was granted an extraordinary increase in executive powers to combat unrest in the far south.[134] By 19 September 2006 (after Sonthi overthrew the Thai government), the army admitted that it was still unsure whom to negotiate with.[135]

National Reconciliation Commission[edit]

In March 2005, respected former Prime Minister Anand Panyarachun was appointed chairman of a National Reconciliation Commission, tasked with overseeing the restoration of peace to the south. A fierce critic of the Thaksin-government, Anand frequently criticised the handling of southern unrest, and in particular the State of Emergency Decree. He has been quoted to have said, "The authorities have worked inefficiently. They have arrested innocent people instead of the real culprits, leading to mistrust among locals. So, giving them broader power may lead to increased violence and eventually a real crisis".[136]

Anand submitted the NRC's recommendations on 5 June 2006.[137] Among them were

Note: Some of these websites may be censored for internet access from within Thailand