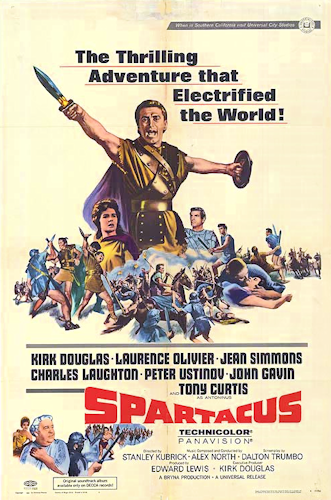

Spartacus (film)

Spartacus is a 1960 American epic historical drama film directed by Stanley Kubrick and starring Kirk Douglas in the title role, a slave who leads a rebellion against Rome and the events of the Third Servile War. Adapted by Dalton Trumbo from Howard Fast's 1951 novel of the same title,[3] the film also stars Laurence Olivier as Roman general and politician Marcus Licinius Crassus, Charles Laughton as Sempronius Gracchus, Peter Ustinov as slave trader Lentulus Batiatus, and John Gavin as Julius Caesar. Jean Simmons played Spartacus' wife Varinia, a fictional character, and Tony Curtis played the fictional slave Antoninus.

Spartacus

Spartacus

1951 novel

by Howard Fast

- October 6, 1960 (DeMille Theatre, New York City)

197 minutes

United States

English

$60 million (initial release)

Douglas, whose company Bryna Productions was producing the film, removed original director Anthony Mann after the first week of shooting. Kubrick, with whom Douglas had made Paths of Glory (1957), was brought on board to take over direction.[4] It was the only film directed by Kubrick where he did not have complete artistic control. Screenwriter Dalton Trumbo was blacklisted at the time as one of the Hollywood Ten. Douglas publicly announced that Trumbo was the screenwriter of Spartacus, and President John F. Kennedy crossed American Legion picket lines to view the film, helping to end blacklisting;[5][6][7] Howard Fast's book had also been blacklisted and he had to self-publish the original edition.

The film won four Academy Awards (Best Supporting Actor for Ustinov, Best Cinematography, Best Art Direction and Best Costume Design) from six nominations. It also received six nominations at the Golden Globes, including Woody Strode‘s only career Golden Globe nomination (for Best Supporting Actor), ultimately winning one (Best Motion Picture – Drama). At the time of the film’s release, it was the biggest moneymaker in Universal Studios' history, which it remained until it was surpassed by Airport (1970).[8]

In 2017, it was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."[9]

Plot[edit]

In the first century BC, the Roman Republic has slid into corruption, its menial work done by slaves. One slave, a Thracian named Spartacus, is so uncooperative in his position in a mining pit that he is sentenced to death by starvation. By chance, he is displayed to Roman businessman Lentulus Batiatus, who – impressed by his ferocity – purchases Spartacus for his gladiatorial school and instructs trainer Marcellus to not overdo his indoctrination, believing the slave "has quality". Amid the abuse, Spartacus forms a quiet relationship with Varinia, a serving woman whom he refuses to rape when she is sent to "entertain" him in his cell. The two are forced to endure numerous humiliations for defying the conditions of servitude.

Batiatus receives a visit from the wealthy Roman senator Marcus Licinius Crassus, who aims to become dictator of Rome. Crassus eventually buys Varinia, and for the amusement of his companions arranges for Spartacus and others to fight to the death. When Spartacus is disarmed, his opponent, an Ethiopian named Draba, spares his life in a burst of defiance and attacks the Roman audience, only to be speared in the back by a guard and killed by Crassus. The next day, with the ludus' atmosphere still tense over this episode, Batiatus sends Varinia away to Crassus' house in Rome. Spartacus kills Marcellus, who was taunting him over his affections, and their fight escalates into a riot. Batiatus flees while the gladiators overwhelm their guards and escape into the countryside.

Spartacus is elected chief of the fugitives and decides to lead them out of Italy and back to their homes. They plunder country estates as they go, collecting enough money to buy sea transport from Rome's foes, the pirates of Cilicia. Many slaves join the group, making it as large as an army. Among the new arrivals is Varinia, who escaped while being delivered to Crassus. Another is Antoninus, a slave entertainer who also fled Crassus' service after finding out Crassus expected Antoninus to become his sex slave. Spartacus feels inadequate because of his lack of education. However, he proves an excellent leader and organizes his diverse followers into a tough and self-sufficient community. Varinia, now his informal wife, becomes pregnant.

The Roman Senate becomes increasingly alarmed as Spartacus defeats every army sent against him. Crassus' opponent Gracchus knows that his rival will try to use the crisis as a justification for seizing control of the Roman army. To try to prevent this, Gracchus channels as much military power as possible into the hands of his own protégé, the young senator Julius Caesar. Although Caesar lacks Crassus' contempt for the lower classes of Rome, he mistakes the man's rigid outlook for a patrician. Thus, when Gracchus reveals that he has bribed the Cilicians to get Spartacus out of Italy and rid Rome of the slave army, Caesar regards such tactics as beneath him and goes over to Crassus.

Crassus uses a bribe of his own to make the pirates abandon Spartacus and has the Roman army secretly force the rebels away from the coastline towards Rome. Amid panic that Spartacus means to sack the city, the Senate gives Crassus absolute power. Now surrounded by Roman legions, Spartacus persuades his men to die fighting. Just by rebelling and proving themselves human, he says that they have struck a blow against slavery. In the ensuing battle, most of the slave army is massacred. The Romans try to locate the rebel leader for special punishment by offering a pardon (and return to enslavement) if the men will identify Spartacus. Every surviving man responds by shouting "I'm Spartacus!". Crassus has them all sentenced to death by crucifixion along the Via Appia, where the revolt began.

Meanwhile, after finding Varinia and Spartacus' newborn son, Crassus takes them prisoner. He is disturbed by the idea that Spartacus can command more love and loyalty than he can, and hopes to compensate by making Varinia as devoted to him as she was to her former husband. When she rejects him, he furiously seeks out Spartacus (whom he recognizes from having watched him at Batiatus' school) and forces him to fight Antoninus to the death. The survivor is to be crucified, along with all the other slaves. Spartacus kills Antoninus to spare him this terrible fate. The incident leaves Crassus worried about Spartacus' potential to live in legend as a martyr. In other matters, he is also worried about Caesar, who he senses will someday eclipse him.

Gracchus, having seen Rome fall into tyranny, commits suicide. Before doing so, he bribes his friend Batiatus to rescue Spartacus' family from Crassus and carry them away to freedom. On the way out of Rome, the group passes under Spartacus' cross. Varinia comforts him in his dying moments by showing him his son, who will grow up free and knowing who his father was.

Reception[edit]

Box office[edit]

Spartacus was a commercial success upon its release and became the highest-grossing film of 1960. In its first year from 304 dates (including 116 in 25 countries outside the US and Canada), it had grossed $17 million,[48] including nearly $1.5 million from over half a million admission in over a year at the DeMille Theatre.[49] By January 1963, the film had earned theatrical rentals of $14 million in the United States and Canada.[67] The 1967 re-release increased its North American rentals to $14.6 million.[68]

"I'm Spartacus!"[edit]

In the climactic scene, recaptured slaves are asked to identify Spartacus in exchange for leniency. Spartacus tries to identify himself, but his attempt is thwarted when each of his comrades proclaims himself to be Spartacus, thus sharing his fate. The documentary Trumbo[16] suggests that this scene was meant to dramatize the solidarity of those accused of being Communist sympathizers during the McCarthy era, who refused to implicate others, thus were blacklisted.[84]

This scene is the basis for an in-joke in Kubrick's next film, Lolita (1962), where Humbert asks Clare Quilty, "Are you Quilty?" to which he replies, "No, I'm Spartacus. Have you come to free the slaves or something?"[85] Many subsequent films, television shows, and advertisements have referenced or parodied the iconic scene. One of these is the film Monty Python's Life of Brian (1979), which reverses the situation by depicting an entire group undergoing crucifixion all claiming to be Brian, who, it has just been announced, is eligible for release ("I'm Brian." "No, I'm Brian." "I'm Brian and so's my wife.")[85] Further examples have been documented[85] in David Hughes' The Complete Kubrick[86] and Jon Solomon's The Ancient World in Cinema.[87]

The audio of the scene was also played at the start of each The Wall Live (2010–2013) tour show as an introduction to the song "In the Flesh?".[88]

In an episode of the U.S. version of The Office, Michael Scott inadvertently reveals he does not understand the point of the "I am Spartacus!" moment. He says, "I've seen that movie half a dozen times, and I still don't know who the real Spartacus is" which he says is what makes the film a "classic whodunit."[89]

The scene is referenced in the Starz television series, Spartacus: War of the Damned (2013), where many of Spartacus' lieutenants claim to be him while raiding separate areas of the Italian countryside. However, the purpose behind the line is different in this case, as Spartacus and his comrades are attempting to confuse their Roman adversaries about the rebel leader's whereabouts.[90]

In the film That Thing You Do! (1996), drummer Guy Patterson (Tom Everett Scott) uses the catch phrase (as "I am Spartacus") numerous times to identify himself. He later spontaneously names his signature jazz solo "I am Spartacus" in the studio and then jams to it with Del Paxton (Bill Cobbs).[91] The jazz drum solo was composed by Tom Hanks, the film's director.