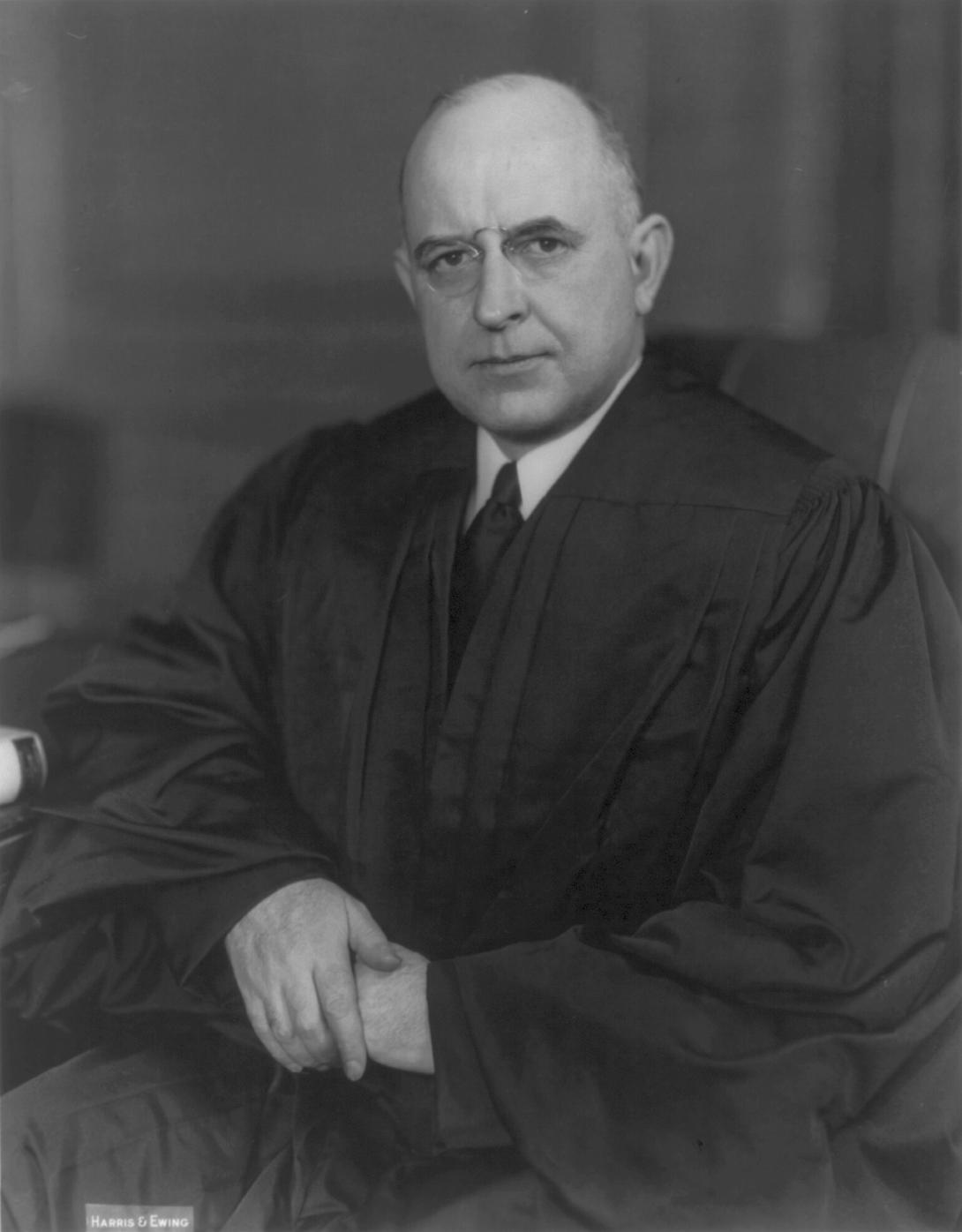

Stanley Forman Reed

Stanley Forman Reed (December 31, 1884 – April 2, 1980) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1938 to 1957.[2][3] He also served as U.S. Solicitor General from 1935 to 1938.

"Stanley F. Reed" redirects here. Not to be confused with Stanley Foster Reed.

Stanley Forman Reed

Franklin D. Roosevelt

December 31, 1884

Minerva, Kentucky, U.S.

April 2, 1980 (aged 95)

Huntington, New York, U.S.

2

Born in Mason County, Kentucky, Reed established a legal practice in Maysville, Kentucky, and won election to the Kentucky House of Representatives. He attended law school but did not graduate, making him the latest-serving Supreme Court Justice who did not graduate from law school. After serving in the United States Army during World War I, Reed emerged as a prominent corporate attorney and took positions with the Federal Farm Board and the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. He took office as Solicitor General in 1935, and defended the constitutionality of several New Deal policies.

After the retirement of Associate Justice George Sutherland, President Franklin D. Roosevelt successfully nominated Reed to the Supreme Court. Reed served until his retirement in 1957, and was succeeded by Charles Evans Whittaker. Reed wrote the majority opinion in cases such as Smith v. Allwright, Gorin v. United States, and Adamson v. California. He authored dissenting opinions in cases such as Illinois ex rel. McCollum v. Board of Education.

Early life and education[edit]

Reed was born in the small town of Minerva in Mason County, Kentucky on December 31, 1884, the son of wealthy physician John Reed and Frances (Forman) Reed. The Reeds and Formans traced their history to the earliest colonial period in America, and these family heritages were impressed upon young Stanley at an early age.[4][5][6][7] At the age of 10, Reed moved with his family to Maysville, Kentucky where his father practiced medicine. The family resided downtown in a prominent home known as Phillips' Folly.

Reed attended Kentucky Wesleyan College and received a B.A. degree in 1902. He then attended Yale University as an undergraduate, and obtained a second B.A. in 1906. He studied law at the University of Virginia (where he was a member of St. Elmo Hall) and Columbia University, but did not obtain a law degree.[4][5][6] Reed married the former Winifred Elgin in May 1908. The couple had two sons, John A. and Stanley Jr., who both became attorneys.[6][7] In 1909 he traveled to France and studied at the Sorbonne as an auditeur bénévole.[4][5][6][7][a]

Legacy[edit]

An extensive collection of Reed's personal and official papers, including his Supreme Court files, is archived at the University of Kentucky in Lexington, where they are open for research.