Status epilepticus

Status epilepticus (SE), or status seizure, is a medical condition consisting of a single seizure lasting more than 5 minutes, or 2 or more seizures within a 5-minute period without the person returning to normal between them.[3][1] Previous definitions used a 30-minute time limit.[2] The seizures can be of the tonic–clonic type, with a regular pattern of contraction and extension of the arms and legs, or of types that do not involve contractions, such as absence seizures or complex partial seizures.[1] Status epilepticus is a life-threatening medical emergency, particularly if treatment is delayed.[1]

Status epilepticus

Regular pattern of contraction and extension of the arms and legs, movement of one part of the body, unresponsive[1]

>5 minutes[1]

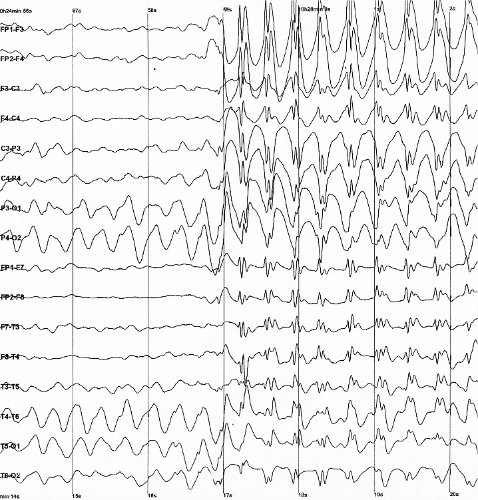

Blood sugar, imaging of the head, blood tests, electroencephalogram[1]

Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, movement disorders, meningitis, delirium[1]

Benzodiazepines, fosphenytoin, phenytoin,[1] paraldehyde (rarely used)

~20% thirty-day risk of death[1]

40 per 100,000 people per year[2]

Status epilepticus may occur in those with a history of epilepsy as well as those with an underlying problem of the brain.[2] These underlying brain problems may include trauma, infections, or strokes, among others.[2][4] Diagnosis often involves checking the blood sugar, imaging of the head, a number of blood tests, and an electroencephalogram.[1] Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures may present similarly to status epilepticus.[1] Other conditions that may also appear to be status epilepticus include low blood sugar, movement disorders, meningitis, and delirium, among others.[1] Status epilepticus can also appear when tuberculous meningitis becomes very severe.

Benzodiazepines are the preferred initial treatment, after which typically phenytoin is given.[1] Possible benzodiazepines include intravenous lorazepam as well as intramuscular injections of midazolam.[5] A number of other medications may be used if these are not effective, such as phenobarbital, propofol, or ketamine.[1] After initial treatment with benzodiazepines, typical antiseizure drugs should be given, including valproic acid (valproate), fosphenytoin, levetiracetam, or a similar substance(s).[6] While empirically based treatments exist, few head-to-head clinical trials exist, so the best approach remains undetermined.[6] This said, "consensus-based" best practices are offered by the Neurocritical Care Society.[6] Intubation may be required to help maintain the person's airway.[1] Between 10% and 30% of people who have status epilepticus die within 30 days.[1] The underlying cause, the person's age, and the length of the seizure are important factors in the outcome.[2] Status epilepticus occurs in up to 40 per 100,000 people per year.[2] Those with status epilepticus make up about 1% of people who visit the emergency department.[1]

Only 25% of people who experience seizures or status epilepticus have epilepsy.[13] The following is a list of possible causes:

Diagnosis[edit]

Diagnostic criteria vary, though most practitioners diagnose as status epilepticus for: one continuous, unremitting seizure lasting longer than five minutes,[14] or recurrent seizures without regaining consciousness between seizures for greater than five minutes.[1] Previous definitions used a 30-minute time limit.[2]

Nonconvulsive status epilepticus is believed to be under-diagnosed.[15]

New-onset refractory status epilepticus (NORSE) is defined as status epilepticus that does not respond to an anticonvulsant and lacks an obvious cause after two days of investigation.[16][17]

Prognosis[edit]

While sources vary, about 16 to 20% of first-time SE patients die;[6] with other sources indicating between 10 and 30% of such patients die within 30 days.[1] Further, 10-50% of first-time SE patients experience lifelong disabilities.[6] In the 30% mortality figure, the great majority of these people have an underlying brain condition causing their status seizure such as brain tumor, brain infection, brain trauma, or stroke. People with diagnosed epilepsy who have a status seizure also have an increased risk of death if their condition is not stabilized quickly, their medication and sleep regimen adapted and adhered to, and stress and other stimulant (seizure trigger) levels controlled. However, with optimal neurological care, adherence to the medication regimen, and a good prognosis (no other underlying uncontrolled brain or other organic disease), the person—even people who have been diagnosed with epilepsy—in otherwise good health can survive with minimal or no brain damage, and can decrease risk of death and even avoid future seizures.[13]

Prognosis of refractory status epilepticus

A different prognosis method was developed for refractory status epilepticus (RSE). Prognosis studies have shown that there is no clear structure of the symptoms; since they range from gastrointestinal to flu-like symptoms, which are considered to be mild and only represent 10%, while the remaining majority of 90% of the clinical cases were unknown. It was found that it takes a period of 1 to 14 days for the patient to reach the prodromal stage in which the episode is yet to come for the first time. It was found that the frequency of those initial seizures starts from a short and inconsistent seizures that lasts for a few hours and may extend to few days. It can simply strike to hundreds of seizures per day, which is the stage that needed an urgent medical intervene in which the patient expected to be in the intensive care unit (ICU) as soon as possible. Typically focal seizures are the most common among those cases.[33]

Epidemiology[edit]

In the United States, about 40 cases of SE occur annually per 100,000 people.[2] This includes about 10–20% of all first seizures.[34]

Prevalence

It was found that status epilepticus is more prevalent among African Americans than Caucasian Americans by threefold in North London, and that Asian children have recorded a relatively higher susceptibility of developing the more severe form of febrile seizures. These ethnic distribution rates indicate the genetic contribution to the susceptibility of status epilepticus. Also, studies have shown that status epilepticus is more common in males.[34]

Aetiology

Many studies have found out that age is the most related factor to the etiology of status epilepticus, since 52% of febrile seizures was found in children, while for adults acute cerebralvascular cases was more common, side by side with hypoxia and other metabolic causes.[34]

Research[edit]

Allopregnanolone is being studied in a clinical trial by the Mayo Clinic to treat super-resistant status epilepticus.[35]