Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy that flourished in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome.[1] The Stoics believed that the practice of virtue is enough to achieve eudaimonia: a well-lived life. The Stoics identified the path to achieving it with a life spent practicing the four virtues in everyday life: wisdom, courage, temperance or moderation, and justice, and living in accordance with nature. It was founded in the ancient Agora of Athens by Zeno of Citium around 300 BC.

Alongside Aristotle's ethics, the Stoic tradition forms one of the major founding approaches to virtue ethics.[2] The Stoics are especially known for teaching that "virtue is the only good" for human beings, and that external things, such as health, wealth, and pleasure, are not good or bad in themselves (adiaphora) but have value as "material for virtue to act upon". Many Stoics—such as Seneca and Epictetus—emphasized that because "virtue is sufficient for happiness", a sage would be emotionally resilient to misfortune. The Stoics also held that certain destructive emotions resulted from errors of judgment, and they believed people should aim to maintain a will (called prohairesis) that is "in accordance with nature". Because of this, the Stoics thought the best indication of an individual's philosophy was not what a person said but how a person behaved.[3] To live a good life, one had to understand the rules of the natural order since they believed everything was rooted in nature.

Stoicism flourished throughout the Roman and Greek world until the 3rd century AD, and among its adherents was Emperor Marcus Aurelius. It experienced a decline after Christianity became the state religion in the 4th century AD. Since then, it has seen revivals, notably in the Renaissance (Neostoicism) and in the contemporary era (modern Stoicism).[4]

History[edit]

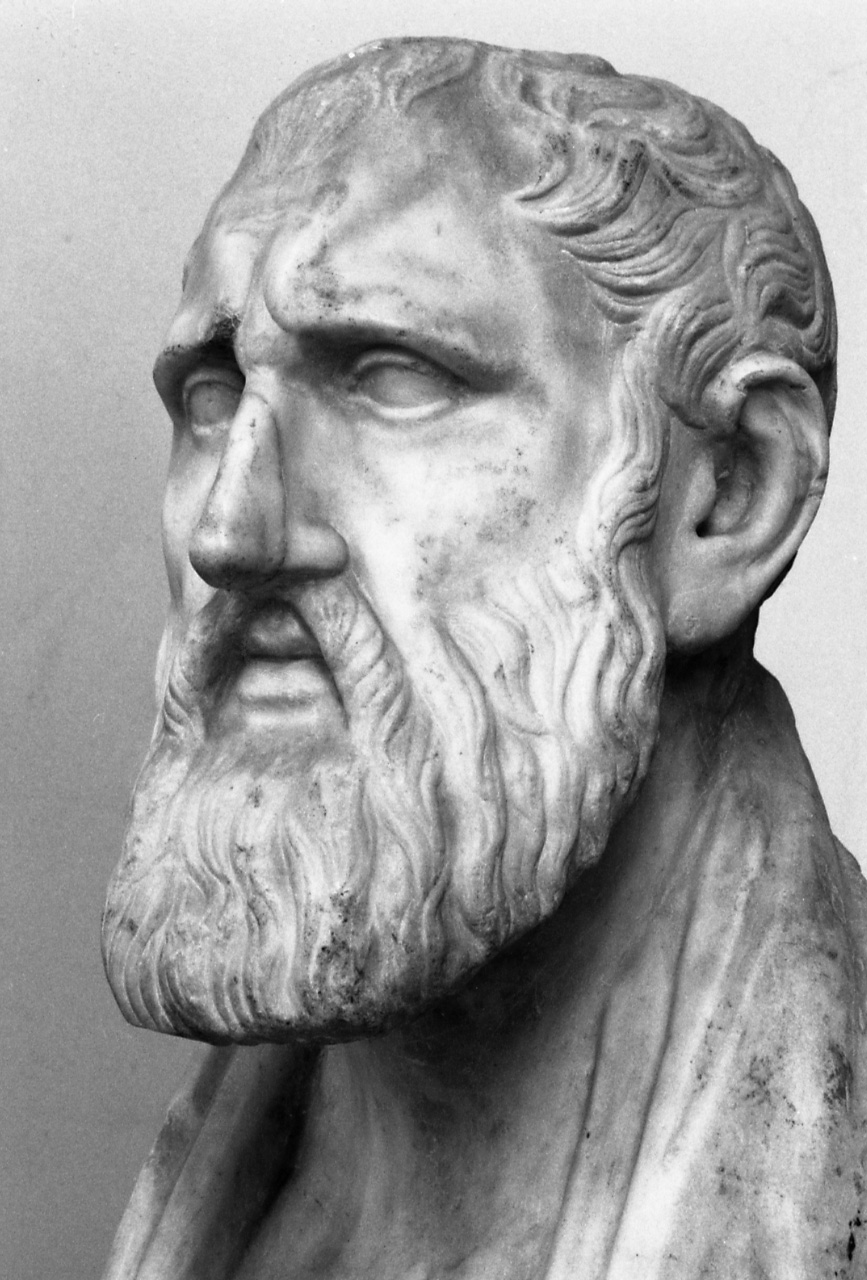

The name Stoicism derives from the Stoa Poikile (Ancient Greek: ἡ ποικίλη στοά), or "painted porch", a colonnade decorated with mythic and historical battle scenes on the north side of the Agora in Athens where Zeno of Citium and his followers gathered to discuss their ideas, near the end of the 4th century BC.[5] Unlike the Epicureans, Zeno chose to teach his philosophy in a public space. Stoicism was originally known as Zenonism. However, this name was soon dropped, likely because the Stoics did not consider their founders to be perfectly wise and to avoid the risk of the philosophy becoming a cult of personality.[6]

Zeno's ideas developed from those of the Cynics (brought to him by Crates of Thebes), whose founding father, Antisthenes, had been a disciple of Socrates. Zeno's most influential successor was Chrysippus, who followed Cleanthes as leader of the school, and was responsible for molding what is now called Stoicism.[7] Stoicism became the foremost popular philosophy among the educated elite in the Hellenistic world and the Roman Empire[8] to the point where, in the words of Gilbert Murray, "nearly all the successors of Alexander [...] professed themselves Stoics".[9] Later Roman Stoics focused on promoting a life in harmony within the universe within which we are active participants.

Scholars[10] usually divide the history of Stoicism into three phases: the Early Stoa, from Zeno's founding to Antipater, the Middle Stoa, including Panaetius and Posidonius, and the Late Stoa, including Musonius Rufus, Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius. No complete works survived from the first two phases of Stoicism. Only Roman texts from the Late Stoa survived.[11]

Legacy[edit]

Neoplatonism[edit]

Plotinus criticized both Aristotle's Categories and those of the Stoics. His student Porphyry, however, defended Aristotle's scheme. He justified this by arguing that they be interpreted strictly as expressions, rather than as metaphysical realities. The approach can be justified, at least in part, by Aristotle's own words in The Categories. Boethius' acceptance of Porphyry's interpretation led to their being accepted by Scholastic philosophy.

Christianity[edit]

The Fathers of the Church regarded Stoicism as a "pagan philosophy";[53][54] nonetheless, early Christian writers employed some of the central philosophical concepts of Stoicism. Examples include the terms "logos", "virtue", "Spirit", and "conscience".[30] But the parallels go well beyond the sharing and borrowing of terminology. Both Stoicism and Christianity assert an inner freedom in the face of the external world, a belief in human kinship with Nature or God, a sense of the innate depravity—or "persistent evil"—of humankind,[30] and the futility and temporary nature of worldly possessions and attachments. Both encourage Ascesis with respect to the passions and inferior emotions, such as lust, and envy, so that the higher possibilities of one's humanity can be awakened and developed. Stoic influence can also be seen in the works of Ambrose of Milan, Marcus Minucius Felix, and Tertullian.[55]

Modern[edit]

The modern usage is a "person who represses feelings or endures patiently".[56] The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy's entry on Stoicism notes, "the sense of the English adjective 'stoical' is not utterly misleading with regard to its philosophical origins".[57]

The revival of Stoicism in the 20th century can be traced to the publication of Problems in Stoicism[58][59] by A. A. Long in 1971, and also as part of the late 20th century surge of interest in virtue ethics. Contemporary Stoicism draws from the late 20th and early 21st century spike in publications of scholarly works on ancient Stoicism. Beyond that, the current Stoicist movement traces its roots to the work of Albert Ellis, who developed rational emotive behavior therapy,[60] as well as Aaron T. Beck, who is regarded by many as the father to early versions of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).