Storm chasing

Storm chasing is broadly defined as the deliberate pursuit of any severe weather phenomenon, regardless of motive, but most commonly for curiosity, adventure, scientific investigation, or for news or media coverage.[2] A person who chases storms is known as a storm chaser or simply a chaser.

"Stormchaser" redirects here. For other uses, see Storm chaser.While witnessing a tornado is the single biggest objective for most chasers, many chase thunderstorms and delight in viewing cumulonimbus and related cloud structures, watching a barrage of hail and lightning, and seeing what skyscapes unfold. A smaller number of storm chasers attempt to intercept tropical cyclones and waterspouts.[3]

Nature of and motivations for chasing[edit]

Storm chasing is chiefly a recreational endeavor, with chasers usually giving their motives as photographing or video recording a storm, or for various personal reasons.[4] These can include the beauty of the views afforded by the sky and land, the mystery of not knowing precisely what will unfold, the journey to an undetermined destination on the open road, intangible experiences such as feeling one with a much larger and more powerful natural world,[5] the challenge of correctly forecasting and intercepting storms with optimal vantage points,[6] and pure thrill seeking.[7] Pecuniary interests and competition may also be components; in contrast, camaraderie is common.

Although scientific work is sometimes cited as a goal, direct participation in such work is almost always impractical during the actual chase except for chasers collaborating in an organized university or government project.[8] Many chasers also act as storm spotters, reporting their observations of hazardous weather to relevant authorities. These reports greatly benefit real-time warnings with ground truth information, as well as science as a whole by increasing the reliability of severe storm databases used in climatology and other research (which ultimately boosts forecast and warning skill).[9] Additionally, many recreational chasers submit photos and videos to researchers as well as to the U.S. National Weather Service (NWS) for spotter training.[10]

Storm chasers are not generally paid to chase, with the exception of television media crews in certain television market areas, video stringers and photographers (freelancers mostly, but some staff), and researchers such as graduate meteorologists and professors. An increasing number sell storm videos and pictures and manage to make a profit. A few operate "chase tour" services, making storm chasing a recently developed form of niche tourism.[11][12] Financial returns usually are relatively meager given the expenses of chasing, with most chasers spending more than they take in and very few making a living solely from chasing. Chasers are also generally limited by the duration of the season in which severe storms are most likely to develop, usually the local spring and/or summer.

No degree or certification is required to be a storm chaser, and many chases are mounted independently by amateurs and enthusiasts without formal training. Local National Weather Service offices do hold storm spotter training classes, usually early in the spring.[13] Some offices collaborate to produce severe weather workshops oriented toward operational meteorologists.

Storm chasers come from a wide variety of occupational and socioeconomic backgrounds. Though a fair number are professional meteorologists, most storm chasers are from other occupational fields, which may include any number of professions that have little or nothing to do with meteorology. A relatively high proportion possess college degrees and a large number live in the central and southern United States. Many are lovers of nature with interests that also include flora, fauna, geology, volcanoes, aurora, meteors, eclipses, and astronomy.[3]

History[edit]

The first person to gain public recognition as a storm chaser was David Hoadley (born 1938), who began chasing North Dakota storms in 1956, systematically using data from area weather offices and airports. He is widely considered the pioneer storm chaser[3] and was the founder and first editor of Storm Track magazine.

Neil B. Ward (1914–1972) subsequently brought research chasing to the forefront in the 1950s and 1960s, enlisting the help of the Oklahoma Highway Patrol to study storms. His work pioneered modern storm spotting and made institutional chasing a reality.

The first coordinated storm chasing activity sponsored by institutions was undertaken as part of the Alberta Hail Studies project beginning in 1969.[14] Vehicles[15] were outfitted with various meteorological instrumentation and hail-catching apparatus and were directed into suspected hail regions of thunderstorms by a controller at a radar site.[16] The controller communicated with the vehicles by radio.

In 1972, the University of Oklahoma (OU) in cooperation with the National Severe Storms Laboratory (NSSL) began the Tornado Intercept Project, with the first outing taking place on 19 April of that year.[17] This was the first large-scale tornado chasing activity sponsored by an institution. It culminated in a brilliant success in 1973 with the Union City, Oklahoma tornado providing a foundation for tornado and supercell morphology that proved the efficacy of storm chasing field research.[18] The project produced the first legion of veteran storm chasers, with Hoadley's Storm Track magazine bringing the community together in 1977.

Storm chasing then reached popular culture in three major spurts: in 1978 with the broadcast of an episode of the television program In Search of...; in 1985 with a documentary on the PBS series Nova; and in May 1996 with the theatrical release of Twister, a Hollywood blockbuster which provided an action-packed but heavily fictionalized glimpse of the hobby. Further early exposure to storm chasing resulted from notable magazine articles, beginning in the late 1970s in Weatherwise magazine.

Various television programs and increased coverage of severe weather by the news media, especially since the initial video revolution in which VHS ownership became widespread by the early 1990s, substantially elevated awareness of and interest in storms and storm chasing. The Internet in particular has contributed to a significant increase in the number of storm chasers since the mid-to-late 1990s. A sharp increase in the general public impulsively wandering about their local area in search of tornadoes similarly is largely attributable to these factors. The 2007–2011 Discovery Channel reality series Storm Chasers produced another surge in activity. Over the years the nature of chasing and the characteristics of chasers shifted.

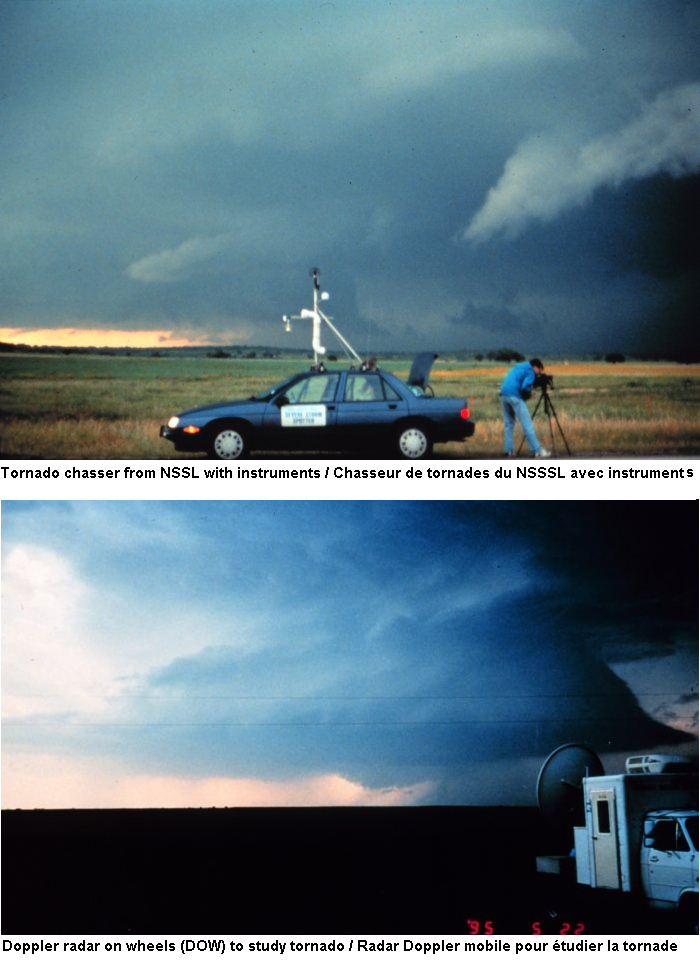

From their advent in the 1970s until the mid-1990s, scientific field projects were occasionally conducted in the Great Plains during the spring.[18] The first of the seminal VORTEX projects occurred in 1994–1995[19] and was soon followed by various field experiments each spring, with another large project, VORTEX2,[20] in 2009–2010.[21] Since the mid-1990s, most storm chasing science, with the notable exception of large field projects, consists of mobile Doppler weather radar intercepts.

Typical storm chase[edit]

Chasing often involves driving thousands of miles in order to witness the relatively short window of time of active severe thunderstorms. It is not uncommon for a chaser to end up empty handed on any particular day. Storm chasers' degrees of involvement, competencies, philosophies, and techniques vary widely, but many chasers spend a significant amount of time forecasting, both before going on the road as well as during the chase, utilizing various sources for weather data. Most storm chasers are not meteorologists, and many chasers expend significant time and effort in learning meteorology and the intricacies of severe convective storm prediction through both study and experience.[22]

Besides the copious driving to, from, and during chases, storm chasing is punctuated with contrasting periods of long waiting and ceaseless action. Downtime can consist of sitting under sun-baked skies for hours, playing pickup sports, evaluating data, or visiting landmarks while awaiting convective initiation. During an inactive pattern, this down time can persist for days. When storms are occurring, there is often little or no time to eat or relieve oneself and finding fuel can cause frustrating delays and detours. Navigating obstacles such as rivers and areas with inadequate road networks is a paramount concern. Only a handful of chasers decide to chase in Dixie Alley, an area of the Southern United States in which trees and road networks heavily obscure the storms and often large tornadoes. The combination of driving and waiting has been likened to "extreme sitting".[23] A "bust" occurs when storms do not fire, sometimes referred to as "severe clear", when storms fire but are missed, when storms fire but are meager, or when storms fire after dusk.

Most chasing is accomplished by driving a motor vehicle of any make or model, whether it be a sedan, van, pickup truck, or SUV, however, a few individuals occasionally fly planes and television stations in some markets use helicopters. Research projects sometimes employ aircraft, as well.

Geographical, seasonal, and diurnal activity[edit]

Storm chasers are most active in the spring and early summer, particularly May and June, across the Great Plains of the United States (extending into Canada) in an area colloquially known as Tornado Alley, with many hundred individuals active on some days during this period. This coincides with the most consistent tornado days[24] in the most desirable topography of the Great Plains. Not only are the most intense supercells common here, but due to the moisture profile of the atmosphere the storms tend to be more visible than locations farther east where there are also frequent severe thunderstorms. There is a tendency for chases earlier in the year to be farther south, shifting farther north with the jet stream as the season progresses. Storms occurring later in the year tend to be more isolated and slower moving, both of which are also desirable to chasers.[22]

Chasers may operate whenever significant thunderstorm activity is occurring, whatever the date. This most commonly includes more sporadic activity occurring in warmer months of the year bounding the spring maximum, such as the active month of April and to a lesser extent March. The focus in the summer months is the Central or Northern Plains states and the Prairie Provinces, the Upper Midwest, or on to just east of the Colorado Front Range. An annually inconsistent and substantially smaller peak of severe thunderstorm and tornado activity also arises in the transitional months of autumn, particularly October and November. This follows a pattern somewhat the reverse of the spring pattern with the focus beginning in the north then dropping south and with an overall eastward shift. In the area with the most consistent significant tornado activity, the Southern Plains, the tornado season is intense but is relatively brief whereas central to northern and eastern areas experience less intense and consistent activity that is diffused over a longer span of the year.[3]

Advancing technology since the mid-2000s led to chasers more commonly targeting less amenable areas (i.e. hilly or forested) that were previously eschewed when continuous wide visibility was critical. These advancements, particularly in-vehicle weather data such as radar, also led to an increase in chasing after nightfall. Most chasing remains during daylight hours with active storm intercepting peaking from mid-late afternoon through early-to-mid evening. This is dictated by a chaser's schedule (availability to chase) and by when storms form, which usually is around peak heating during the mid-to-late afternoon but on some days occurs in early afternoon or even in the morning. An additional advantage of later season storms is that days are considerably longer than in early spring. Morning or early afternoon storms tend to be associated with stronger wind shear and thus most often happen earlier in the spring season or later during the fall season.

Some organized chasing efforts have also begun in the Top End of the Northern Territory and in southeastern Australia,[25][26] with the biggest successes in November and December. A handful of individuals are also known to be chasing in other countries, including the United Kingdom, Israel, Italy, Spain, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Finland, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Poland, Bulgaria, Slovenia, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Estonia, Argentina, South Africa, Bangladesh, and New Zealand; although many people trek to the Great Plains of North America from these and other countries around the world (especially from the UK). The number of chasers and number countries where chasers are active expanded at an accelerating pace in Europe from the 1990s–2010s.

Ethics[edit]

A growing number of experienced storm chasers advocate the adoption of a code of ethics in storm chasing featuring safety, courtesy, and objectivity as the backbone.[28][55] Storm chasing is a highly visible recreational activity (which is also associated with science) that is vulnerable to sensationalist media promotion.[56] Veteran storm chasers Chuck Doswell and Roger Edwards deemed reckless storm chasers as "yahoos".[57] Doswell and Edwards believe poor chasing ethics at TV news stations add to the growth of "yahoo" storm chasing.[58] A large lawsuit[59] was filed against the parent company of The Weather Channel in March 2019 for allegedly keeping on contract storm chaser drivers with a demonstrated pattern of reckless driving which ultimately led to a fatal collision (killing themselves and a storm spotter in the other vehicle) when running a stop sign in Texas in 2017.[60] Edwards and Rich Thompson, among others, also expressed concern about pernicious effects of media profiteering[61] with Matt Crowther, among others, agreeing in principle but viewing sales as not inherently corrupting.[62] Self-policing is seen as the means to mold the hobby. There is occasional discussion among chasers that at some point government regulation may be imposed due to increasing numbers of chasers and because of poor behavior by some individuals; however, many chasers do not expect this eventuality and almost all oppose regulations—as do some formal studies of dangerous leisure activities which also advocate deliberative self-policing.[63]

As there is for storm chaser conduct, there is concern about chaser responsibility. Since some chasers are trained in first aid and even first responder procedures, it is not uncommon for tornado chasers to be first on a scene and tending to storm victims or treating injuries at the site of a disaster in advance of emergency personnel and other outside aid.[64]

Aside from questions concerning their ethical values and conduct, many have been accredited for giving back to the community in several ways. Just before the Joplin tornado, Storm Chaser[65] Jeff Piotrowski provided advanced warning to Officer Brewer of Joplin local law enforcement, prompting them to activate the emergency sirens. Though lives were lost, many who survived accredited their survival to the siren.[66] After a storm has passed storm chasers are often the first to arrive on the scene to help assist in the aftermath. An unexpected and yet increasingly more common result of storm chasers is the data they provide to storm research from their videos, social video posts and documentation of storms they encounter. After the El Reno tornado in 2013, portals were created for chasers to submit their information to help in the research of the deadly storm.[67] The El Reno Tornado Environment Display (TED) was created to show a synchronized view of the submitted video footage overlaying radar images of the storm with various chasers' positions.[68]