The Duchess of Malfi

The Duchess of Malfi (originally published as The Tragedy of the Dutchesse of Malfy) is a Jacobean revenge tragedy written by English dramatist John Webster in 1612–1613.[1] It was first performed privately at the Blackfriars Theatre, then later to a larger audience at The Globe, in 1613–1614.[2]

For other uses, see The Duchess of Malfi (disambiguation).The Duchess of Malfi

Antonio Bologna

Delio

Daniel de Bosola

The Cardinal

Ferdinand

Castruchio

The Duchess of Malfi

Cariola

Julia

1613 or 1614

Blackfriars Theatre, London

Published in 1623, the play is loosely based on events that occurred between 1508 and 1513 surrounding Giovanna d'Aragona, Duchess of Amalfi (d. 1511), whose father, Enrico d'Aragona, Marquis of Gerace, was an illegitimate son of Ferdinand I of Naples. As in the play, she secretly married Antonio Beccadelli di Bologna after the death of her first husband Alfonso I Piccolomini, Duke of Amalfi.

The play begins as a love story, when the Duchess marries beneath her class, and ends as a nightmarish tragedy as her two brothers undertake their revenge, destroying themselves in the process. Jacobean drama continued the trend of stage violence and horror set by Elizabethan tragedy, under the influence of Seneca.[3] The complexity of some of the play's characters, particularly Bosola and the Duchess, and Webster's poetic language, have led many critics to consider The Duchess of Malfi among the greatest tragedies of English renaissance drama.

There are also minor roles including courtiers, servants, officers, a mistress, the Duchess's children, executioners, etc.

Synopsis[edit]

The play is set in the court of Malfi (Amalfi), Italy, from 1504 to 1510. The recently widowed Duchess falls in love with Antonio, a lowly steward. Her brothers, Ferdinand and the Cardinal, forbid her from remarrying, seeking to defend their inheritance and desperate to avoid a degrading association with a social inferior. Suspicious of her, they hire Bosola to spy on her. She elopes with Antonio and bears him three children secretly. Bosola eventually discovers that the Duchess is pregnant but does not know who the father is.

Ferdinand, shown by now to be a depraved lunatic, threatens and disowns the Duchess. In an attempt to escape, she and Antonio concoct a story that Antonio has swindled her out of her fortune and must flee into exile. The Duchess takes Bosola into her confidence, unaware that he is Ferdinand's spy, and arranges for him to deliver her jewellery to Antonio at his hiding-place in Ancona. She will join them later, while pretending to make a pilgrimage to a nearby town. The Cardinal hears of the plan, instructs Bosola to banish the two lovers, and sends soldiers to capture them. Antonio escapes with their eldest son, but the Duchess, her maid, and her two younger children are returned to Malfi and die at the hands of Bosola's executioners, who are under Ferdinand's orders. This experience leads Bosola to turn against the brothers, and he decides to take up the cause of "revenge for the Duchess of Malfi" (5.2).

The Cardinal confesses his part in the killing of the Duchess to his mistress, Julia, then murders her with a poisoned Bible. Bosola overhears the Cardinal plotting to kill him, so he visits the darkened chapel to kill the Cardinal at his prayers. Instead, he mistakenly kills Antonio, who has just returned to Malfi to attempt a reconciliation with the Cardinal. Bosola then stabs the Cardinal, who dies. In the brawl that follows, Ferdinand and Bosola stab each other to death.

Antonio's elder son by the Duchess appears in the final scene and takes his place as the heir to the Malfi fortune. The son's decision is in spite of his father's explicit wish that he "fly the court of princes", a corrupt and increasingly deadly environment.

The conclusion is controversial for some readers because they find reason to believe the inheriting son is not the rightful heir of the Duchess. The play briefly mentions a son who is the product of her first marriage and would therefore have a stronger claim to the duchy.[4] Other scholars believe the mention of a prior son is just a careless error in the text.

Sources[edit]

Webster's principal source was in William Painter's The Palace of Pleasure (1567), which was a translation of François de Belleforest's French adaptation of Matteo Bandello's Novelle (1554). Bandello had known Antonio Beccadelli di Bologna in Milan before his assassination. He recounted the story of Antonio's secret marriage to Giovanna after the death of her first husband, stating that it brought down the wrath of her two brothers, one of whom, Luigi d'Aragona, was a powerful cardinal under Pope Julius II. Bandello says that the brothers arranged the kidnapping of the Duchess, her maid, and two of her three children by Antonio, all of whom were then murdered. Antonio, unaware of their fate, escaped to Milan with his oldest son, where he was later assassinated by a gang led by one Daniele Bozzolo.[5]

Webster's play follows this story fairly faithfully, but departs from the source material by depicting Bozzolo as a conflicted figure who repents, kills Antonio by mistake, then turns on the brothers killing them both.[6] In fact the brothers were never accused of the crime in their lifetimes and died of natural causes.

Theatrical devices[edit]

The play makes use of various theatrical devices,[12] some of them derived from Senecan Tragedy which includes violence and bloodshed on the stage. Act III, Scene IV is a mime scene, in which a song is sung in honour of the Cardinal, who gives up his robes and invests himself with the attire of a soldier, and then performs the act of banishing the Duchess. The whole scene is commented upon by two pilgrims, who condemn the harsh behaviour of the Cardinal towards the Duchess. That the scene is set against the backdrop of the Shrine of Our Lady of Loretto, a religious place, adds to its sharp distinction between good and evil, justice and injustice.

Act V, Scene iii, features an important theatrical device, echo, which seems to emanate from the grave of the Duchess, in her voice. In its totality, it reads: "Deadly accent. A thing of sorrow. That suits it best. Ay, wife's voice. Be mindful of thy safety. O fly your fate. Thou art a dead thing. Never see her more." The echo repeats the last words of what Antonio and Delio speak, but is selective. It adds to the sense of the inevitability of Antonio's death, while highlighting the role of fate.

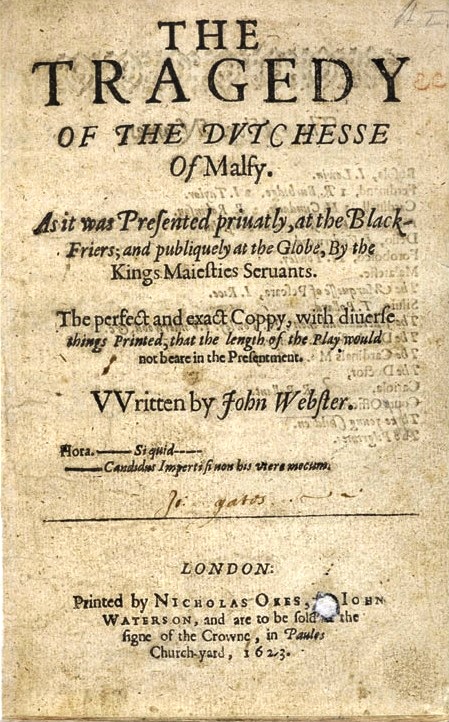

The 1623 quarto[edit]

The Duchess of Malfi was first performed between 1613 and 1614 by the King's Men, an acting group to which Shakespeare belonged. The printer was Nicholas Okes and the publisher was John Waterson. However, the play was not printed in quarto (a smaller, less expensive edition than the larger folio) until 1623. The title page of this particular edition tells us that the play was printed privately. The title page also informs readers that the play text includes numerous passages that were cut for performance. The 1623 quarto is the only substantive version of the play in circulation today, and modern editions and productions are based on it. Notable is that, on the title page of the 1623 quarto, a clear distinction is drawn between the play in performance and the play as a text to be read. [14]