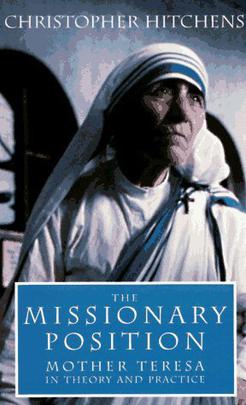

The Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice

The Missionary Position: Mother Teresa in Theory and Practice is a book by the journalist and polemicist Christopher Hitchens published in 1995. It is a critique of the work and philosophy of Mother Teresa, the founder of an international Roman Catholic religious congregation, and it challenges the mainstream media's assessment of her charitable efforts. The book's thesis, as summarized by one critic, was that "Mother Teresa is less interested in helping the poor than in using them as an indefatigable source of wretchedness on which to fuel the expansion of her fundamentalist Roman Catholic beliefs."[1]

Author

English

1995

United Kingdom

128 pages

271/.97 B 20

BX4406.5.Z8 H55 1995

Only 128 pages in length,[1] it was re-issued in paperback and ebook form with a foreword by Thomas Mallon in 2012.[2]

The introduction is devoted to Mother Teresa's acceptance of an award from the government of Haiti, which Hitchens uses to discuss her relationship to the Duvalier regime. From her praise of the country's corrupt first family, he writes, "Other questions arise … all of them touching on matters of saintliness, modesty, humility and devotion to the poor."[15] He adds other examples of Mother Teresa's relationships with powerful people with what he considers dubious reputations. He quickly reviews Mother Teresa's saintly reputation in books devoted to her and describes the process of beatification and canonization under Pope John Paul II. Finally, he disclaims any quarrel with Mother Teresa herself and says he is more concerned with the public view of her: "What follows here is an argument not with a deceiver but with the deceived."[16]

The first section, "A Miracle", discusses the popular view of Mother Teresa and focuses on the 1969 BBC documentary Something Wonderful for God which brought her to the attention of the general public and served as the basis for the book of the same title by Malcolm Muggeridge. Hitchens says that Calcutta's reputation as a place of abject poverty, "a hellhole", is not deserved, but nevertheless provides a sympathetic context for Mother Teresa's work there.[17] He quotes from conversations between Muggeridge and Mother Teresa, providing his own commentary. He quotes Muggeridge's description of "the technically unaccountable light" the BBC team filmed in the interior of the Home of the Dying as "the first authentic photographic miracle".[18] Hitchens contrasts this with the cameraman's statement that what Muggeridge thought was a miracle was the result of them using the latest Kodak low light film.[19]

The second section, "Good Works and Heroic Deeds", has three chapters:

The third section, "Ubiquity", has two chapters:

Reception[edit]

In the London Review of Books, Amit Chaudhuri praised the book: "Hitchens's investigations have been a solitary and courageous endeavour. The book is extremely well-written, with a sanity and sympathy that tempers its irony." He commented that the portrait "is in danger of assuming the one-dimensionality of the Mother Teresa of her admirers", and that he finished the book without much more of an idea of the character and motivations of Mother Teresa.[27] In The New York Times Bruno Maddox wrote: "Like all good pamphlets... it is very short, zealously over-written and rails wild". He called its arguments "rather convincing", made "with consummate style."[1] The Sunday Times said: "A dirty job but someone had to do it. By the end of this elegantly written, brilliantly argued piece of polemic, it is not looking good for Mother Teresa."[28]

Bill Donohue, president of the Catholic League, in a critical review that appeared in 1996 wrote: "If this sounds like nonsense, well, it is."[29] Though he admired Hitchens generally as a writer and "provocateur", Donohue has said that Hitchens was "totally overrated as a scholar ... sloppy in his research".[30] Donohue released a book to coincide with Saint Teresa's canonization, entitled "Unmasking Mother Teresa's Critics". In an interview, Donohue said, "Unlike Hitchens, who wrote a 98-page book with no footnotes, no endnotes, no bibliography, no attribution at all, just 98 pages of unsupported opinion, I have a short book too. But I actually have more footnotes than I have pages in the book. That's because I want people to check my sources."[31]

The New York Review of Books provided a series of contrasting assessments of both Mother Teresa's and Hitchens's views over several months, beginning with a review of The Missionary Position by Murray Kempton who found Hitchens persuasive that Mother Teresa's "love for the poor is curiously detached from every expectation or even desire for the betterment of their mortal lot". His essay matched the tone of Hitchens's prose: "The swindler Charles Keating gave her $1.25 million—most dubiously his own to give—and she rewarded him with the 'personalized crucifix' he doubtless found of sovereign use as an ornamental camouflage for his pirate flag." He condemned her for baptizing those "incapable of informed consent" and for "her service at Madame Duvalier's altar". Kempton saw Hitchens's work as a contrast with his avowed atheism and more representative of a Christian whose protests "resonate with the severities of orthodoxy".[32] In reply, James Martin, S.J., culture editor of the magazine America, acknowledged that Mother Teresa "accepted donations from dictators and other unsavory characters [and] tolerates substandard medical conditions in her hospices." Without mentioning Hitchens, he called Kempton's review "hysterical" and made two points, that she took advantage of high quality medical care for herself most likely at the urging of other members of her order and that the care her order provides is "comfort and solace" for the dying, not "primary health care" as other orders do. Martin closed his remarks by stating that there "would seem to be two choices" regarding those poor people in the developing world who die neglected: "First, to cluck one’s tongue that such a group of people should even exist. Second, to act: to provide comfort and solace to these individuals as they face death. Mr. Kempton chooses the former. Mother Teresa, for all of her faults, chooses the latter."[33]

Literary critic and sinologist Simon Leys wrote that "the attacks which are being directed at Mother Teresa all boil down to one single crime: she endeavors to be a Christian, in the most literal sense of the word". He compared her accepting "the hospitality of crooks, millionaires, and criminals" to Christ's relations with unsavory individuals, said that on his deathbed he would prefer the comfort Mother Teresa's order provides to the services of "a modern social worker". He defended secretly baptizing the dying as "a generous mark of sincere concern and affection". He concluded by comparing journalists' treatment of Mother Teresa to Christ being spat upon.[33]

In reply to Leys, Hitchens noted that in April 1996 Mother Teresa welcomed Princess Diana's divorce after advising the Irish to oppose the right of civil divorce and remarriage in a November 1995 national referendum. He thought this buttressed his case that Mother Teresa preached different gospels to the rich and the poor. He disputed whether Christ ever praised someone like the Duvaliers or accepted funds "stolen from small and humble savers" by the likes of Charles Keating. He identified Leys with religious leaders who "claim that all criticism is abusive, blasphemous, and defamatory by definition".[34] Leys replied in turn, writing that Hitchens' book "contain[ed] a remarkable number of howlers on elementary aspects of Christianity"[35] and accusing Hitchens of "a complete ignorance of the position of the Catholic Church on the issues of marriage, divorce, and remarriage" and a "strong and vehement distaste for Mother Teresa."[36]

In 1999, Charles Taylor of Salon called The Missionary Position "brilliant" and wrote that it "should have laid the myth of Mother Teresa’s saintliness to rest once and for all."[37]