The Sandman (comic book)

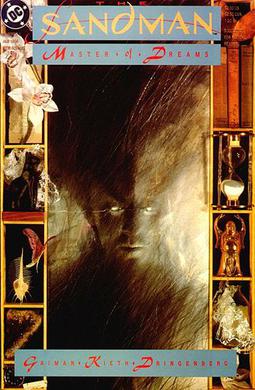

The Sandman is a comic book written by Neil Gaiman and published by DC Comics. Its artists include Sam Kieth, Mike Dringenberg, Jill Thompson, Shawn McManus, Marc Hempel, Bryan Talbot, and Michael Zulli, with lettering by Todd Klein and covers by Dave McKean. The original series ran for 75 issues from January 1989 to March 1996. Beginning with issue No. 47, it was placed under DC's Vertigo imprint, and following Vertigo's retirement in 2020, reprints have been published under DC's Black Label imprint.

For other uses, see Sandman (disambiguation).The Sandman

- DC Comics (1989–1993)

- Vertigo (1993–2020)

- DC Black Label (2020–present)

Monthly

- The Sandman (January 1989–March 1996)

- The Sandman: The Dream Hunters (1999)

- The Sandman: Overture (October 2013–November 2015)

- The Sandman (75)

- The Sandman: The Dream Hunters (4)

- The Sandman: Overture (6)

- The Sandman

Sam Kieth

Mike Dringenberg

Chris Bachalo

Michael Zulli

Kelley Jones

Charles Vess

Colleen Doran

Matt Wagner

Stan Woch

Bryan Talbot

Shawn McManus

Duncan Eagleson

John Watkiss

Jill Thompson

P. Craig Russell

Alec Stevens

Mike Allred

Shea Anton Pensa

Gary Amaro

Marc Hempel

Glyn Dillon

Dean Ormston

Teddy Kristiansen

Richard Case

Jon J Muth

The Sandman: The Dream Hunters

P. Craig Russell

The Sandman: Overture

J. H. Williams III

- The Sandman

Mike Dringenberg

Malcolm Jones III

Steve Parkhouse

Charles Vess

P. Craig Russell

George Pratt

Dick Giordano

Stan Woch

Shawn McManus

Vince Locke

John Watkiss

Alec Stevens

Mark Buckingham

Mike Allred

Steve Leialoha

Tony Harris

Marc Hempel

D'Israeli

Glyn Dillon

Teddy Kristiansen

Richard Case

Michael Zulli

Jon J Muth

The Sandman: The Dream Hunters

P. Craig Russell

The Sandman: Overture

J. H. Williams III

- Robbie Busch

Steve Oliff

Danny Vozzo

Lovern Kindzierski / Digital Chameleon

Jon J Muth

Sherilyn van Valkenburgh

The titular main character of The Sandman is Dream, also known as Morpheus and other names, who is one of the seven Endless. The other Endless are Destiny, Death, Desire, Despair, Delirium (formerly Delight), and Destruction (also known as 'The Prodigal'). The series is famous for Gaiman's trademark use of anthropomorphic personification of various metaphysical entities, while also blending mythology and history in its horror setting within the DC Universe.[2] The Sandman is a story about stories and how Morpheus, the Lord of Dreams, is captured and subsequently learns that sometimes change is inevitable.[3] The Sandman was Vertigo's flagship title, and is available as a series of ten trade paperbacks, a recolored five-volume Absolute hardcover edition with slipcase, a three-volume omnibus edition, a black-and-white Annotated edition; it is also available for digital download.

Critically acclaimed, The Sandman was among the first graphic novels to appear on The New York Times Best Seller list, along with Maus, Watchmen, and The Dark Knight Returns. It was one of six graphic novels to make Entertainment Weekly's "100 best reads from 1983 to 2008", ranking at No. 46.[4] Norman Mailer described the series as "a comic strip for intellectuals".[5] The series has exerted considerable influence over the fantasy genre and graphic novel medium since its publication and is often regarded as one of the greatest graphic novels of all time.

Various film and television versions of Sandman have been developed. In 2013, Warner Bros. announced that a film adaptation starring Joseph Gordon-Levitt was in production, but Gordon-Levitt dropped out in 2016. In July 2020, September 2021 and September 2022, three full-cast audio dramas were released exclusively through Audible starring James McAvoy, which were narrated by Gaiman and dramatized and directed by Dirk Maggs. In August 2022, Netflix released a television adaptation starring Tom Sturridge.

Themes and genre[edit]

The Sandman comic book series falls within the dark fantasy genre, albeit in a more contemporary and modern setting. Critic Marc Buxton described the book as a "masterful tale that created a movement of mature dark fantasy" which was largely unseen in previous fantasy works before it.[57] The comic book also falls into the genres of urban fantasy, epic fantasy, historical drama, and superhero. It is written as a metaphysical examination of the elements of fiction,[58] which Neil Gaiman accomplished through the artistic use of unique anthropomorphic personifications, mythology, legends, historical figures and occult culture, making up most of the major and minor characters as well as the plot device and even the settings of the story.[58] In its earliest story arcs, the Sandman mythos existed primarily in the DC Universe, and as such numerous DC characters made some appearances or were mentioned. Later, the series would reference the DCU less often, while continuing to exist in the same universe.[59]

Critic Hilary Goldstein described the comic book as "about the concept of dreams more so than the act of dreaming".[59] In the early issues, responsibility and rebirth were the primary themes of the story.[60] As Dream finally liberates himself from his occultist captors, he returns to his kingdom which had fallen on hard times due to his absence, while also facing his other siblings, who each have their own reaction to his return. The story is structured not as a series of unconnected events nor as an incoherent dream, but by having each panel have a specific purpose in the flow of the story.[59] Dreams became the core of every story arc written in the series, and the protagonist's journey became more distinct and deliberate. Many Vertigo books since, such as Transmetropolitan and Y: The Last Man, have adopted this kind of format in their writing, creating a traditional prose only seen in the imprint.[59]

Adaptations into other media[edit]

Film[edit]

Throughout the late 1990s, a film adaptation of the comic was periodically planned by Warner Bros., parent company of DC Comics. Roger Avary was originally attached to direct after the success of Pulp Fiction, collaborating with Pirates of the Caribbean screenwriters Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio in 1996 on a revision of their first script draft, which merged the "Preludes and Nocturnes" storyline with that of "The Doll's House". Avary intended the film to be in part visually inspired by animator Jan Švankmajer's work. Avary was fired after disagreements over the creative direction with executive producer Jon Peters, best known for the 1989 film Batman and the abandoned project Superman Lives. It was due to their meeting on the Sandman film project that Avary and Gaiman collaborated one year later on the script for Beowulf. The project carried on through several more writers and scripts. A later draft by William Farmer, reviewed at Ain't It Cool News,[90] was met with scorn from fans. Gaiman called the last screenplay that Warner Bros. would send him "not only the worst Sandman script I've ever seen, but quite easily the worst script I've ever read".[91] Gaiman has said that his dissatisfaction with how his characters were being treated had dissuaded him from writing any more stories involving the Endless, although he has since written Endless Nights and Sandman Overture.

By 2001, the project had become stranded in development hell. In a Q&A panel at Comic-Con 2007, Gaiman remarked, "I'd rather see no Sandman movie made than a bad Sandman movie. But I feel like the time for a Sandman movie is coming soon. We need someone who has the same obsession with the source material as Peter Jackson had with Lord of the Rings or Sam Raimi had with Spider-Man."[92] That same year, he stated that he could imagine Terry Gilliam as a director for the adaptation: "I would always give anything to Terry Gilliam, forever, so if Terry Gilliam ever wants to do Sandman then as far as I'm concerned Terry Gilliam should do Sandman."[93] In 2013, DC President Diane Nelson said that a Sandman film would be as rich as the Harry Potter universe.[94] David S. Goyer announced in an interview in early December that he would be producing an adaptation of the graphic novel, alongside Joseph Gordon-Levitt and Neil Gaiman. Jack Thorne was hired to write the script.[95] On October 16, 2014, Gaiman clarified that while the film was not announced with the DC slate by Warner Bros., it would instead be distributed by Vertigo and announced with those slate of films.[96] Goyer told Deadline Hollywood in an interview that the studio was very happy with the film's script.[97] According to Deadline Hollywood, the film was to be distributed by New Line Cinema.[98] In October 2015, Goyer revealed that a new screenwriter was being brought on board to revise the script by Jack Thorne and stated that he believed the film would go into production the following year.[99] In March 2016, The Hollywood Reporter revealed that Eric Heisserer was hired to rewrite the film's script.[100] The next day, Gordon-Levitt announced that he had dropped out due to disagreements with the studio over the creative direction of the film.[101] On November 9, 2016, i09 reported that Heisserer had turned in his draft of the script but left the film, stating that the film should be an HBO series instead.[102]

Death