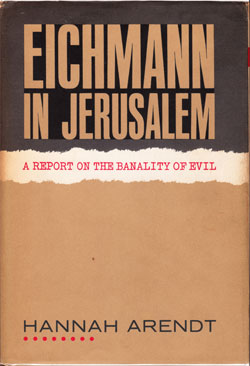

Eichmann in Jerusalem

Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil is a 1963 book by the philosopher and political thinker Hannah Arendt. Arendt, a Jew who fled Germany during Adolf Hitler's rise to power, reported on the trial of Adolf Eichmann, one of the major organizers of the Holocaust, for The New Yorker. A revised and enlarged edition was published in 1964.

Author

Arendt takes Eichmann's court testimony and the historical evidence available, and she makes several observations about him:

Arendt suggests that this most strikingly discredits the idea that the Nazi criminals were manifestly psychopathic and different from "normal" people. From this document, many concluded that situations such as the Holocaust can make even the most ordinary of people commit horrendous crimes with the proper incentives, but Arendt adamantly disagreed with this interpretation, as Eichmann was voluntarily following the Führerprinzip. Arendt said that moral choice remains even under totalitarianism, and that this choice has political consequences even when the chooser is politically powerless:

Arendt mentions, as a case in point, Denmark:

On Eichmann's personality, Arendt concludes:

Arendt ended the book by writing:

Beyond her discussion of Eichmann himself, Arendt discusses several additional aspects of the trial, its context, and the Holocaust.

Banality of evil[edit]

Arendt's book introduced the expression and concept of the banality of evil.[15] Her thesis is that Eichmann was actually not a fanatic or a sociopath, but instead an average and mundane person who relied on clichéd defenses rather than thinking for himself,[16] was motivated by professional promotion rather than ideology, and believed in success which he considered the chief standard of "good society".[17] Banality, in this sense, does not mean that Eichmann's actions were in any way ordinary, but that his actions were motivated by a sort of complacency which was wholly unexceptional.[18]

Many mid-20th century pundits were favorable to the concept,[19][20] which has been called "one of the most memorable phrases of 20th-century intellectual life,"[21] and it features in many contemporary debates about morality and justice,[16][22] as well as in the workings of truth and reconciliation commissions.[23] Others see the popularization of the concept as a valuable warrant against walking negligently into horror, as the evil of banality, in which failure to interrogate received wisdom results in individual and systemic weakness and decline.[24]