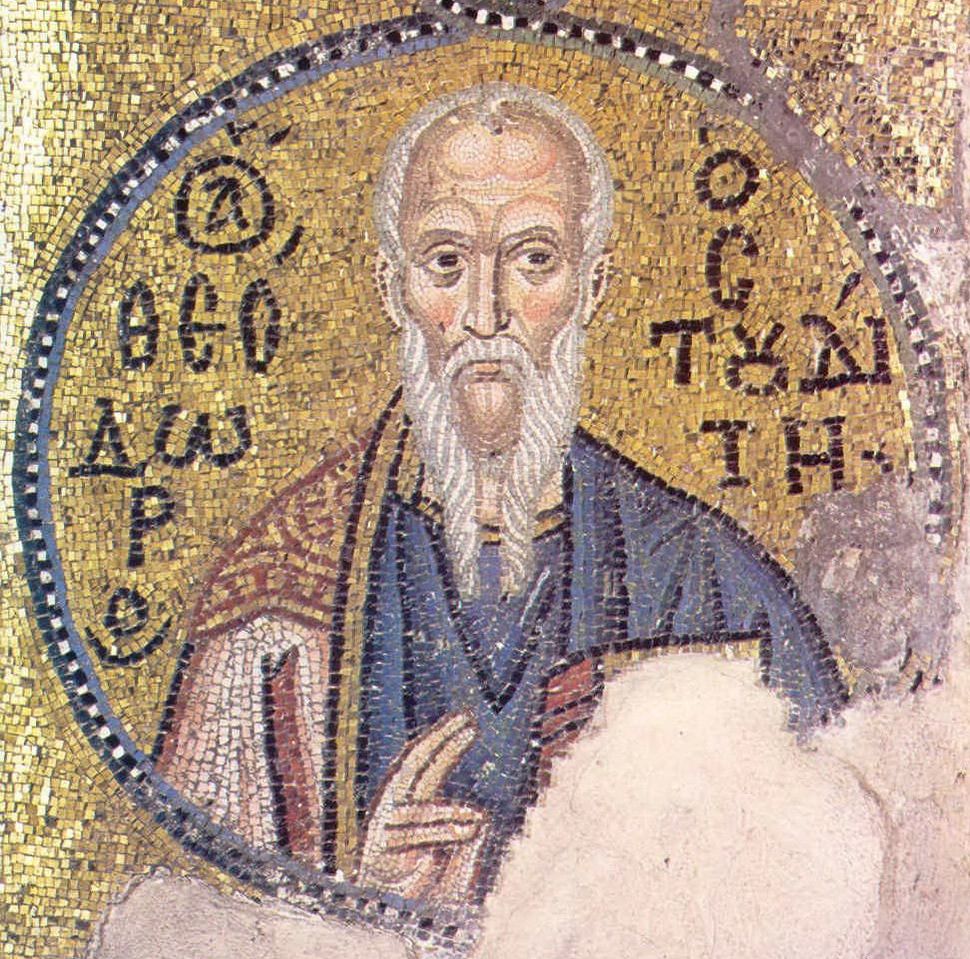

Theodore the Studite

Theodore the Studite (Medieval Greek: Θεόδωρος ὁ Στουδίτης; 759–826), also known as Theodorus Studita and Saint Theodore of Stoudios/Studium, was a Byzantine Greek monk and abbot of the Stoudios Monastery in Constantinople.[1][2] He played a major role in the revivals both of Byzantine monasticism and of classical literary genres in Byzantium. He is known as a zealous opponent of iconoclasm, one of several conflicts that set him at odds with both emperor and patriarch. Throughout his life he maintained letter correspondences with many important political and cultural figures of the Byzantine empire;[3] this included many women, such as the composer and nun Kassia, who was much influenced by his teachings.[4]

Theodore the Studite

759

Constantinople

(modern-day Istanbul, Turkey)

11 November 826 (aged 66/67)

Cape Akritas

(modern-day Tuzla, Istanbul, Turkey)

11 November (East), 12 November (West)

Biography[edit]

Family and childhood[edit]

Theodore was born in Constantinople in 759.[2] He was the oldest son of Photeinos, an important financial official in the palace bureaucracy,[5] and Theoktiste, herself the offspring of a distinguished Constantinopolitan family.[6] The brother of Theoktiste, Theodore's uncle Platon, was an important official in the imperial financial administration.[7] The family therefore controlled a significant portion, if not all, of the imperial financial administration during the reign of Constantine V (r. 741–775).[8] Theodore had two younger brothers (Joseph, later Archbishop of Thessalonica, and Euthymios) and one sister, whose name we do not know.[9]

It has often been assumed that Theodore's family belonged to the iconodule party during the first period of Byzantine Iconoclasm. There is however no evidence to support this, and their high position in the imperial bureaucracy of the time renders any openly iconodule position highly unlikely. Furthermore, when Platon left his office and entered the priesthood in 759, he was ordained by an abbot who, if he was not actively iconoclastic himself, at the very least offered no resistance to the iconoclastic policies of Constantine V. The family as a whole was most likely indifferent to the question of icons during this period.[10]

According to the later hagiographical literature, Theodore received an education befitting his family's station and from the age of seven was instructed by a private tutor, eventually concentrating in particular on theology. It is however not clear that these opportunities were available to even the most well-placed Byzantine families of the eighth century, and it is possible that Theodore was at least partially an autodidact.[11]

Early monastic career[edit]

Following the death of Emperor Leo IV (r. 775–780) in 780, Theodore's uncle Platon, who had lived as a monk in the Symbola Monastery in Bithynia since 759, visited Constantinople, and persuaded the entire family of his sister, Theoktiste, to likewise take monastic vows. Theodore, together with his father and brothers, sailed back to Bithynia with Platon in 781, where they set about transforming the family estate into a religious establishment, which became known as the Sakkudion Monastery. Platon became abbot of the new foundation, and Theodore was his "right hand." The two sought to order the monastery according to the writings of Basil of Caesarea.[12]

During the period of the regency of Eirene, Abbot Platon emerged as a supporter of the Patriarch Tarasios, and was a member of Tarasios's iconodule party at the Second Council of Nicaea, where the veneration of icons was declared orthodox. Shortly thereafter Tarasios himself ordained Theodore as a priest. In 794, Theodore became abbot of the Sakkudion Monastery, while Platon withdrew from the daily operation of the monastery and dedicated himself to silence.[13]

Conflict with Constantine VI[edit]

Also in 794, Emperor Constantine VI (r. 776–797) decided to separate from his first wife, Maria of Amnia, and to marry Maria's kubikularia (Lady-in-waiting), Theodote, a cousin of Theodore the Studite.[14] Although the Patriarch may initially have resisted this development, as a divorce without proof of adultery on the part of the wife could be construed as illegal, he ultimately gave way. The marriage of Constantine and Theodote was celebrated in 795, although not by the patriarch, as was normal, but by a certain Joseph, a priest of Hagia Sophia.[15]

A somewhat obscure chain of events followed (the so-called "Moechian controversy," from the Greek moichos, "adulterer"), in which Theodore initiated a protest against the marriage from the Sakkudion Monastery, and appears to have demanded the excommunication, not only of the priest Joseph, but also of all who had received communion from him, which, as Joseph was a priest of the imperial church, included implicitly the emperor and his court.[16] This demand had no official weight, however, and Constantine appears to have attempted to make peace with Theodore and Platon (who, on account of his marriage, were now his relatives), inviting them to visit him during a sojourn at the imperial baths of Prusa in Bithynia. In the event neither appeared.[17]

As a result, imperial troops were sent to the Sakkudion Monastery, and the community was dispersed. Theodore was flogged, and, together with ten other monks, banished to Thessaloniki, while Platon was imprisoned in Constantinople.[18] The monks arrived in Thessaloniki in March 797, but did not remain for long; in August of the same year Constantine VI was blinded and overthrown, and his mother Irene, the new empress, lifted the exile.[19]

Legacy[edit]

Theodore's revival of the Stoudios monastery had a major effect on the later history of Byzantine monasticism. His disciple, Naukratios, recovered control of the monastery after the end of iconoclasm in 842, and throughout the remainder of the ninth century the Studite abbots continued Theodore's tradition of opposition to patriarchal and imperial authority.[66] Elements of Theodore's Testament were incorporated verbatim in the typika of certain early Athonite monasteries.[67] The most important elements of his reform were its emphases on cenobitic (communal) life, manual labor, and a carefully defined administrative hierarchy.[68]

Theodore also built the Stoudios monastery into a major scholarly center, in particular through its library and scriptorium, which certainly surpassed all other contemporary Byzantine ecclesiastical institutions in this regard.[69] Theodore himself was a pivotal figure in the revival of classical literary forms, in particular iambic verse, in Byzantium, and his criticisms of the iconoclastic epigrams drew a connection between literary skill and orthodox faith.[70] After his death the Stoudios monastery continued to be a vital center for Byzantine hymnography and hagiography, as well as for the copying of manuscripts.[69]

Following the "triumph of Orthodoxy" (i.e. the reintroduction of icons) in 843, Theodore became one of the great heroes of the iconodule opposition. There was no formal process of canonization in Byzantium, but Theodore was soon recognized as a saint. In the Latin West, Theodore’s recognition of papal primacy on the basis of his letters to Pope Paschal I was part of what caused him to be formally canonized by the Catholic Church. His feast day is 11 November in the East and 12 November in the West.[71]

Theodore was an immensely prolific author; among his most important works are: