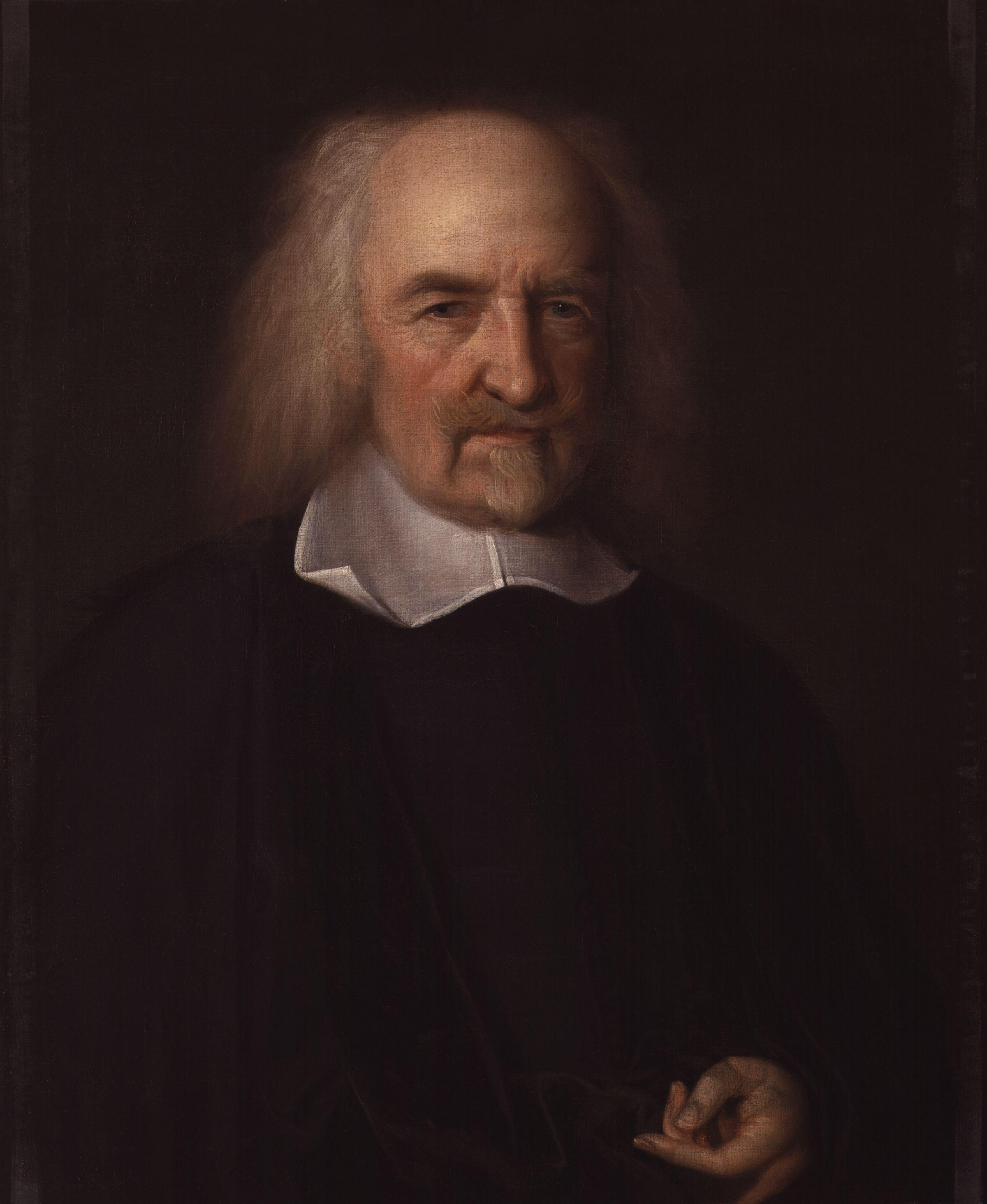

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes (/hɒbz/ HOBZ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book Leviathan, in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory.[4] He is considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy.[5][6]

"Hobbes" redirects here. For other people called Hobbes, see Hobbes (disambiguation).

Thomas Hobbes

4 December 1679 (aged 91)

- De Cive (1647)

- Leviathan (1651)

- De Corpore (1655)

- Behemoth (1681)

Hobbes was born prematurely due to his mother's fear of the Spanish Armada. His early life, overshadowed by his father's departure following a fight, was taken under the care of his wealthy uncle. Hobbes's academic journey began in Westport, leading him to Oxford University, where he was exposed to classical literature and mathematics. He then graduated from the University of Cambridge in 1608. He became a tutor to the Cavendish family, which connected him to intellectual circles and initiated his extensive travels across Europe. These experiences, including meetings with figures like Galileo, shaped his intellectual development.

After returning to England from France in 1641, Hobbes witnessed the destruction and brutality of the English Civil War from 1642 to 1651 between Parliamentarians and Royalists, which heavily influenced his advocacy for governance by an absolute sovereign in Leviathan, as the solution to human conflict and societal breakdown. Aside from social contract theory, Leviathan also popularized ideas such as the state of nature ("war of all against all") and laws of nature. His other major works include the trilogy De Cive (1642), De Corpore (1655), and De Homine (1658) as well as the posthumous work Behemoth (1681).

Hobbes contributed to a diverse array of fields, including history, jurisprudence, geometry, optics, theology, classical translations, ethics, as well as philosophy in general, marking him as a polymath. Despite controversies and challenges, including accusations of atheism and contentious debates with contemporaries, Hobbes's work profoundly influenced the understanding of political structure and human nature.

Biography[edit]

Early life[edit]

Thomas Hobbes was born on 5 April 1588 (Old Style), in Westport, now part of Malmesbury in Wiltshire, England. Having been born prematurely when his mother heard of the coming invasion of the Spanish Armada, Hobbes later reported that "my mother gave birth to twins: myself and fear."[7] Hobbes had a brother, Edmund, about two years older, as well as a sister, Anne.

Although Thomas Hobbes's childhood is unknown to a large extent, as is his mother's name,[8] it is known that Hobbes's father, Thomas Sr., was the vicar of both Charlton and Westport. Hobbes's father was uneducated, according to John Aubrey, Hobbes's biographer, and he "disesteemed learning."[9] Thomas Sr. was involved in a fight with the local clergy outside his church, forcing him to leave London. As a result, the family was left in the care of Thomas Sr.'s older brother, Francis, a wealthy glove manufacturer with no family of his own.

Opposition[edit]

John Bramhall[edit]

In 1654 a small treatise, Of Liberty and Necessity, directed at Hobbes, was published by Bishop John Bramhall.[21][41] Bramhall, a strong Arminian, had met and debated with Hobbes and afterwards wrote down his views and sent them privately to be answered in this form by Hobbes. Hobbes duly replied, but not for publication. However, a French acquaintance took a copy of the reply and published it with "an extravagantly laudatory epistle".[21] Bramhall countered in 1655, when he printed everything that had passed between them (under the title of A Defence of the True Liberty of Human Actions from Antecedent or Extrinsic Necessity).[21]

In 1656, Hobbes was ready with The Questions Concerning Liberty, Necessity and Chance, in which he replied "with astonishing force"[21] to the bishop. As perhaps the first clear exposition of the psychological doctrine of determinism, Hobbes's own two pieces were important in the history of the free will controversy. The bishop returned to the charge in 1658 with Castigations of Mr Hobbes's Animadversions, and also included a bulky appendix entitled The Catching of Leviathan the Great Whale.[42]

Religious views[edit]

The religious opinions of Hobbes remain controversial as many positions have been attributed to him and range from atheism to orthodox Christianity. In the Elements of Law, Hobbes provided a cosmological argument for the existence of God, saying that God is "the first cause of all causes".[44]

Hobbes was accused of atheism by several contemporaries; Bramhall accused him of teachings that could lead to atheism. This was an important accusation, and Hobbes himself wrote, in his answer to Bramhall's The Catching of Leviathan, that "atheism, impiety, and the like are words of the greatest defamation possible".[45] Hobbes always defended himself from such accusations.[46] In more recent times also, much has been made of his religious views by scholars such as Richard Tuck and J. G. A. Pocock, but there is still widespread disagreement about the exact significance of Hobbes's unusual views on religion.

As Martinich has pointed out, in Hobbes's time the term "atheist" was often applied to people who believed in God but not in divine providence, or to people who believed in God but also maintained other beliefs that were considered to be inconsistent with such belief or judged incompatible with orthodox Christianity. He says that this "sort of discrepancy has led to many errors in determining who was an atheist in the early modern period".[47] In this extended early modern sense of atheism, Hobbes did take positions that strongly disagreed with church teachings of his time. For example, he argued repeatedly that there are no incorporeal substances, and that all things, including human thoughts, and even God, heaven, and hell are corporeal, matter in motion. He argued that "though Scripture acknowledge spirits, yet doth it nowhere say, that they are incorporeal, meaning thereby without dimensions and quantity".[48] (In this view, Hobbes claimed to be following Tertullian.) Like John Locke, he also stated that true revelation can never disagree with human reason and experience,[49] although he also argued that people should accept revelation and its interpretations for the reason that they should accept the commands of their sovereign, in order to avoid war.

While in Venice on tour, Hobbes made the acquaintance of Fulgenzio Micanzio, a close associate of Paolo Sarpi, who had written against the pretensions of the papacy to temporal power in response to the Interdict of Pope Paul V against Venice, which refused to recognise papal prerogatives. James I had invited both men to England in 1612. Micanzio and Sarpi had argued that God willed human nature, and that human nature indicated the autonomy of the state in temporal affairs. When he returned to England in 1615, William Cavendish maintained correspondence with Micanzio and Sarpi, and Hobbes translated the latter's letters from Italian, which were circulated among the Duke's circle.[9]