Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree

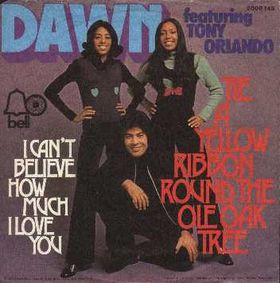

"Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree" is a song recorded by Tony Orlando and Dawn. It was written by Irwin Levine and L. Russell Brown and produced by Hank Medress and Dave Appell, with Motown/Stax backing vocalist Telma Hopkins, Joyce Vincent Wilson and her sister Pamela Vincent on backing vocals.[1] It was a worldwide hit for the group in 1973.

"Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree"

"I Can't Believe How Much I Love You"

February 19, 1973

January 1973

3:20

The single reached the top 10 in ten countries, in eight of which it topped the charts. It reached number one on both the US and UK charts for four weeks in April 1973, number one on the Australian chart for seven weeks from May to July 1973 and number one on the New Zealand chart for ten weeks from June to August 1973. It was the top-selling single in 1973 in both the US and UK.

In 2008, Billboard ranked the song as the 37th biggest song of all time in its issue celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Hot 100.[1] For the 60th anniversary in 2018, the song still ranked in the top 50, at number 46.[2] This song is the origin of the yellow color of the Liberal Party of Cory Aquino, the party that ousted the Marcos dictatorship in the People Power Revolution of 1986.[3]

Synopsis[edit]

The song is told from the point of view of someone who has "done his time" in prison: "Now I've got to know what is and isn't mine" and is uncertain whether his sweetheart will welcome him home: "I'm really still in prison and my love, she holds the key".

He writes to his love, asking her to tie a yellow ribbon around the "ole oak tree" in front of the house (which the bus will pass by) if she wants him to return to her life; if he does not see such a ribbon, he will remain on the bus (taking that to mean he is unwelcome) and understand her reasons ("put the blame on me"). He is afraid to look himself, fearful of not seeing anything, and asks the bus driver to check,

To his amazement, the entire bus cheers the response – there are 100 yellow ribbons around the tree, a sign he is more than welcome.

Origins of the song[edit]

The origin of the idea of a yellow ribbon as remembrance may have been the 19th-century practice that some women allegedly had of wearing a yellow ribbon in their hair to signify their devotion to a husband or sweetheart serving in the U.S. Cavalry. The song "'Round Her Neck She Wears a Yeller Ribbon", tracing back centuries but copyrighted by George A. Norton in 1917, and later inspiring the John Wayne movie She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, is a reference to this.[4][5] The symbol of a yellow ribbon became widely known in civilian life in the 1970s as a reminder that an absent loved one, either in the military or in jail, would be welcomed home on their return.

During the Vietnam War, in October 1971, newspaper columnist Pete Hamill wrote a piece for the New York Post called "Going Home".[6] In it, he told a variant of the story, in which college students on a bus trip to the beaches of Fort Lauderdale make friends with an ex-convict who is watching for a yellow handkerchief on a roadside oak in Brunswick, Georgia. Hamill claimed to have heard this story in oral tradition. In June 1972, nine months later, Reader's Digest reprinted "Going Home". According to L. Russell Brown, he read Hamill's story in the Reader's Digest, and suggested to his songwriting partner Irwin Levine that they write a song based on it.[7] Levine and Brown then registered for copyright the song which they called "Tie a Yellow Ribbon 'Round the Ole Oak Tree". At the time, the writers said they heard the story while serving in the military. Pete Hamill was not convinced and filed suit for infringement. Hamill dropped his suit after folklorists working for Levine and Brown turned up archival versions of the story that had been collected before "Going Home" had been written.[4]

In 1991, Brown said the song was based on a story he had read about a soldier headed home from the Civil War who wrote his beloved that if he was still welcome, she should tie a handkerchief around a certain tree. He said the handkerchief was not particularly romantic, so he and Mr. Levine changed it to a yellow ribbon.[8]

Levine and Brown first offered the song to Ringo Starr, but Al Steckler of Apple Records told them that they should be ashamed of the song and described it as "ridiculous".[7]

The 2008 film The Yellow Handkerchief, conceived as a remake of the original Japanese film, uses a plot based on the Pete Hamill story.[9]

Association with the Iranian Hostage Crisis[edit]

On November 4, 1979, amid the turmoil in Iran following the flight of the Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi to exile in Egypt, a group of students stormed the U.S. embassy in Tehran.[36] seizing more than 60 American hostages. Over the 444 days of the crisis, the song became a national inspiration in America, encouraging Americans to use yellow ribbons as a way to keep the hostages in their hearts and to maintain pressure on President Jimmy Carter to negotiate for their release.[37] With negotiations lagging, Carter ordered a military rescue of the hostage on April 24, 1980, which failed when two helicopters collided; eight U.S. soldiers died in the collision.[38]

The crisis was not resolved until after the 1980 United States Presidential Election; on November 10, 1980, six days after Ronald Reagan won the election, negotiations resumed under U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Warren Christopher, with an agreement signed on January 19, 1981.[39] By that time, the yellow ribbon was ubiquitous across America. Twenty minutes after Reagan's inauguration, the hostages were flown to West Germany by way of Algeria. Five days after their release, Super Bowl XV was played at the Louisiana Superdome, adorned with a massive yellow bow.[40]

Association with the 2014 Hong Kong Protests[edit]

During the 2014 Hong Kong Protests the song was performed by pro-democracy protestors and sympathetic street musicians as a reference to the yellow ribbons that had become a popular symbol of the movement on site (tied to street railings or trees) and on social media.[42] Journalists covering the event described use of the tune as a protest song.[43]