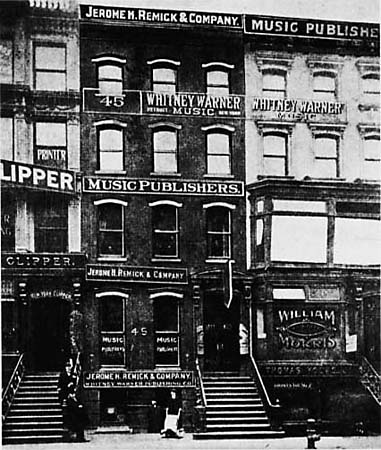

Tin Pan Alley was a collection of music publishers and songwriters in New York City that dominated the popular music of the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Originally, it referred to a specific location on West 28th Street, between Fifth and Sixth Avenues in the Flower District[2] of Manhattan, as commemorated by a plaque on 28th Street between Broadway and Sixth.[3][4][5][6] Several buildings on Tin Pan Alley are protected as New York City designated landmarks, and the section of 28th Street from Fifth to Sixth Avenue is also officially co-named Tin Pan Alley.

The start of Tin Pan Alley is usually dated to about 1885, when a number of music publishers set up shop in the same district of Manhattan. The end of Tin Pan Alley is less clear cut. Some date it to the start of the Great Depression in the 1930s when the phonograph, radio, and motion pictures supplanted sheet music as the driving force of American popular music, while others consider Tin Pan Alley to have continued into the 1950s when earlier styles of music were upstaged by the rise of rock & roll, which was centered on the Brill Building. Brill Building songwriter Neil Sedaka described his employer as being a natural outgrowth of Tin Pan Alley, in that the older songwriters were still employed in Tin Pan Alley firms while younger songwriters such as Sedaka found work at the Brill Building.[7]

Origin of song publishing in New York City[edit]

In the mid-19th century, copyright control of melodies was not as strict, and publishers would often print their own versions of the songs popular at the time. With stronger copyright protection laws late in the century, songwriters, composers, lyricists, and publishers started working together for their mutual financial benefit. Songwriters would literally bang on the doors of Tin Pan Alley businesses to get new material.

The commercial center of the popular music publishing industry changed during the course of the 19th century, starting in Boston and moving to Philadelphia, Chicago and Cincinnati before settling in New York City under the influence of new and vigorous publishers which concentrated on vocal music. The two most enterprising New York publishers were Willis Woodard and T.B. Harms, the first companies to specialize in popular songs rather than hymns or classical music.[10] Naturally, these firms were located in the entertainment district, which, at the time, was centered on Union Square. Witmark was the first publishing house to move to West 28th Street as the entertainment district gradually shifted uptown, and by the late 1890s most publishers had followed their lead.[8]

The biggest music houses established themselves in New York City, but small local publishers – often connected with commercial printers or music stores – continued to flourish throughout the country, and there were important regional music publishing centers in Chicago, New Orleans, St. Louis, and Boston. When a tune became a significant local hit, rights to it were usually purchased from the local publisher by one of the big New York firms.

Contributions to World War II[edit]

During the Second World War, Tin Pan Alley and the federal government teamed up to produce a war song that would inspire the American public to support the fight against the Axis, something they both "seemed to believe ... was vital to the war effort".[25] The Office of War Information was in charge of this project, and believed that Tin Pan Alley contained "a reservoir of talent and competence capable of influencing people's feelings and opinions" that it "might be capable of even greater influence during wartime than that of George M. Cohan's 'Over There' during World War I."[25] In the United States, the song "Over There" has been said to be the most popular and resonant patriotic song associated with World War I.[25] Due to the large fan base of Tin Pan Alley, the government believed that this sector of the music business would be far-reaching in spreading patriotic sentiments.[25]

In the United States Congress, congressmen quarreled over a proposal to exempt musicians and other entertainers from the draft in order to remain in the country to boost morale.[25] Stateside, these artists and performers were continuously using available media to promote the war effort and to demonstrate a commitment to victory.[26] However, the proposal was contested by those who strongly believed that only those who provided more substantial contributions to the war effort should benefit from any draft legislation.[25]

As the war progressed, those in charge of writing the would-be national war song began to understand that the interest of the public lay elsewhere. Since the music would take up such a large amount of airtime, it was imperative that the writing be consistent with the war message that the radio was carrying throughout the nation. In her book, God Bless America: Tin Pan Alley Goes to War, Kathleen E. R. Smith writes that "escapism seemed to be a high priority for music listeners", leading "the composers of Tin Pan Alley [to struggle] to write a war song that would appeal both to civilians and the armed forces".[25] By the end of the war, no such song had been produced that could rival hits like "Over There" from World War I.[25]

Whether or not the number of songs circulated from Tin Pan Alley between 1939 and 1945 was greater than during the First World War is still debated. In his book The Songs That Fought the War: Popular Music and the Home Front, John Bush Jones cites Jeffrey C. Livingstone as claiming that Tin Pan Alley released more songs during World War I than it did in World War II.[27] Jones, on the other hand, argues that "there is also strong documentary evidence that the output of American war-related songs during World War II was most probably unsurpassed in any other war".[27]

Impact[edit]

Landmark designation and co-naming[edit]

In 2019, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission took up the question of preserving five buildings on the north side of the street as a Tin Pan Alley Historic District.[32] The agency designated five buildings (47–55 West 28th Street) individual landmarks on December 10, 2019,[22][33][34] after a concerted effort by the "Save Tin Pan Alley" initiative of the 29th Street Neighborhood Association.[35] Following successful protection of these landmarks, project director George Calderaro and other proponents formed the Tin Pan Alley American Popular Music Project.[36]

On April 2, 2022, 28th Street between Broadway and 6th Avenue was officially co-named "Tin Pan Alley" by the City of New York.[36][37]