Treaty of Trianon

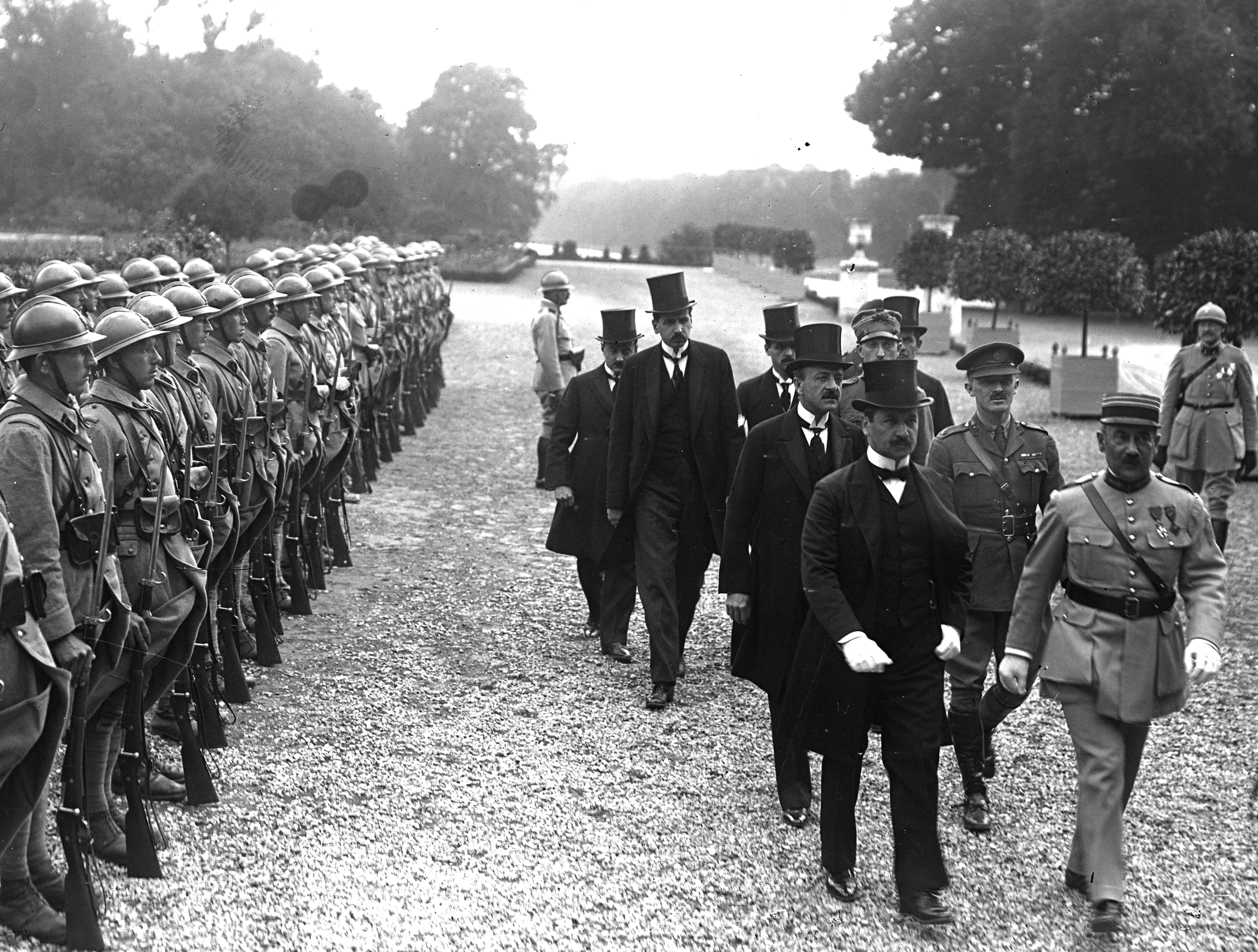

The Treaty of Trianon (French: Traité de Trianon; Hungarian: Trianoni békeszerződés; Italian: Trattato del Trianon; Romanian: Tratatul de la Trianon) often referred to as the Peace Dictate of Trianon[1][2][3][4][5] or Dictate of Trianon[6][7] in Hungary, was prepared at the Paris Peace Conference and was signed in the Grand Trianon château in Versailles on 4 June 1920. It formally ended World War I between most of the Allies of World War I[a] and the Kingdom of Hungary.[8][9][10][11] French diplomats played the major role in designing the treaty, with a view to establishing a French-led coalition of the newly formed states.

Treaty of Peace between the Allied and Associated Powers and Hungary

The treaty regulated the status of the Kingdom of Hungary and defined its borders generally within the ceasefire lines established in November–December 1918 and left Hungary as a landlocked state that included 93,073 square kilometres (35,936 sq mi), 28% of the 325,411 square kilometres (125,642 sq mi) that had constituted the pre-war Kingdom of Hungary (the Hungarian half of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy). The truncated kingdom had a population of 7.6 million, 36% compared to the pre-war kingdom's population of 20.9 million. Though the areas that were allocated to neighbouring countries had a majority of non-Hungarians, in them lived 3.3 million Hungarians – 31% of the Hungarians – who then became minorities.[12][13][14][15] The treaty limited Hungary's army to 35,000 officers and men, and the Austro-Hungarian Navy ceased to exist. These decisions and their consequences have been the cause of deep resentment in Hungary ever since.[16]

The principal beneficiaries were the Kingdom of Romania, the Czechoslovak Republic, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later Yugoslavia), and the First Austrian Republic. One of the main elements of the treaty was the doctrine of "self-determination of peoples", and it was an attempt to give the non-Hungarians their own national states.[17] In addition, Hungary had to pay war reparations to its neighbours.

The treaty was dictated by the Allies rather than negotiated, and the Hungarians had no option but to accept its terms.[17] The Hungarian delegation signed the treaty under protest, and agitation for its revision began immediately.[13][18]

The current boundaries of Hungary are for the most part the same as those defined by the Treaty of Trianon, with minor modifications until 1924 regarding the Hungarian-Austrian border and the transfer of three villages to Czechoslovakia in 1947.[19][20]

After World War I, despite the "self-determination of peoples" idea of the Allied Powers, only one plebiscite was permitted (later known as the Sopron plebiscite) to settle disputed borders on the former territory of the Kingdom of Hungary,[21] settling a smaller territorial dispute between the First Austrian Republic and the Kingdom of Hungary, because some months earlier, the Rongyos Gárda launched a series of attacks to oust the Austrian forces that entered the area. During the Sopron plebiscite in late 1921, the polling stations were supervised by British, French, and Italian army officers of the Allied Powers.[22]

The Hungarian government terminated its union with Austria on 31 October 1918, officially dissolving the Austro-Hungarian dual monarchy. The de facto temporary borders of independent Hungary were defined by the ceasefire lines in November–December 1918. Compared with the pre-war Kingdom of Hungary, these temporary borders did not include:

The territories of Banat, Bačka and Baranja (which included most of the pre-war Hungarian counties of Baranya, Bács-Bodrog, Torontál, and Temes) came under military control by the Kingdom of Serbia and political control by local South Slavs. The Great People's Assembly of Serbs, Bunjevci and other Slavs in Banat, Bačka and Baranja declared union of this region with Serbia on 25 November 1918. The ceasefire line had the character of a temporary international border until the treaty. The central parts of Banat were later assigned to Romania, respecting the wishes of Romanians from this area, which, on 1 December 1918, were present in the National Assembly of Romanians in Alba Iulia, which voted for union with the Kingdom of Romania.

After the Romanian Army advanced beyond this cease-fire line, the Entente powers asked Hungary (Vix Note) to acknowledge the new Romanian territorial gains by a new line set along the Tisza river. Unable to reject these terms and unwilling to accept them, the leaders of the Hungarian Democratic Republic resigned and the Communists seized power. In spite of the country being under Allied blockade, the Hungarian Soviet Republic was formed and the Hungarian Red Army was rapidly set up. This army was initially successful against the Czechoslovak Legions, due to covert food[117] and arms aid from Italy.[118] This made it possible for Hungary to reach nearly the former Galician (Polish) border, thus separating the Czechoslovak and Romanian troops from each other.

After a Hungarian-Czechoslovak cease-fire signed on 1 July 1919, the Hungarian Red Army left parts of Slovakia by 4 July, as the Entente powers promised to invite a Hungarian delegation to the Versailles Peace Conference. In the end, this particular invitation was not issued. Béla Kun, leader of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, then turned the Hungarian Red Army on the Romanian Army and attacked at the Tisza river on 20 July 1919. After fierce fighting that lasted some five days, the Hungarian Red Army collapsed. The Royal Romanian Army marched into Budapest on 4 August 1919.

The Hungarian state was restored by the Entente powers, helping Admiral Horthy into power in November 1919. On 1 December 1919, the Hungarian delegation was officially invited to the Versailles Peace Conference; however, the newly defined borders of Hungary were nearly concluded without the presence of the Hungarians.[119] During prior negotiations, the Hungarian party, along with the Austrian, advocated the American principle of self-determination: that the population of disputed territories should decide by free plebiscite to which country they wished to belong.[119][120] This view did not prevail for long, as it was disregarded by the decisive French and British delegates.[121] According to some opinions, the Allies drafted the outline of the new frontiers[122] with little or no regard to the historical, cultural, ethnic, geographic, economic and strategic aspects of the region.[119][122][123] The Allies assigned territories that were mostly populated by non-Hungarian ethnicities to successor states, but also allowed these states to absorb sizeable territories that were mainly inhabited by Hungarian-speaking populations. For instance, Romania gained all of Transylvania, which was home to 2,800,000 Romanians, but also contained a significant minority of 1,600,000 Hungarians and about 250,000 Germans.[124] The intent of the Allies was principally to strengthen these successor states at the expense of Hungary. Although the countries that were the main beneficiaries of the treaty partially noted the issues, the Hungarian delegates tried to draw attention to them. Their views were disregarded by the Allied representatives.

Some predominantly Hungarian settlements, consisting of more than two million people, were situated in a typically 20–50 km (12–31 mi) wide strip along the new borders in foreign territory. More concentrated groups were found in Czechoslovakia (parts of southern Slovakia), Yugoslavia (parts of northern Délvidék), and Romania (parts of Transylvania).

The final borders of Hungary were defined by the Treaty of Trianon signed on 4 June 1920. Beside exclusion of the previously mentioned territories, they did not include:

By the Treaty of Trianon, the cities of Pécs, Mohács, Baja and Szigetvár, which were under Serb-Croat-Slovene administration after November 1918, were assigned to Hungary. An arbitration committee in 1920 assigned small northern parts of the former Árva and Szepes counties of the Kingdom of Hungary with Polish majority population to Poland. After 1918, Hungary did not have access to the sea, which pre-war Hungary formerly had directly through the Rijeka coastline and indirectly through Croatia-Slavonia.

Representatives of small nations living in the former Austria-Hungary and active in the Congress of Oppressed Nations regarded the treaty of Trianon for being an act of historical righteousness[126] because a better future for their nations was "to be founded and durably assured on the firm basis of world democracy, real and sovereign government by the people, and a universal alliance of the nations vested with the authority of arbitration" while at the same time making a call for putting an end to "the existing unbearable domination of one nation over the other" and making it possible "for nations to organize their relations to each other on the basis of equal rights and free conventions". Furthermore, they believed the treaty would help toward a new era of dependence on international law, the fraternity of nations, equal rights, and human liberty as well as aid civilisation in the effort to free humanity from international violence.[127]