Ubaid period

The Ubaid period (c. 5500–3700 BC)[1] is a prehistoric period of Mesopotamia. The name derives from Tell al-'Ubaid where the earliest large excavation of Ubaid period material was conducted initially in 1919 by Henry Hall and later by Leonard Woolley.[2]

In South Mesopotamia the period is the earliest known period on the alluvial plain although it is likely earlier periods exist obscured under the alluvium.[3] In the south it has a very long duration between about 5500 and 3800 BC when it is replaced by the Uruk period.[1]

In Northern Mesopotamia the period runs only between about 5300 and 4300 BC.[1] It is preceded by the Halaf period and the Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period and succeeded by the Late Chalcolithic period.

History of research[edit]

The term "Ubaid period" was coined at a conference in Baghdad in 1930, where at the same time the Jemdet Nasr and Uruk periods were defined.[4]

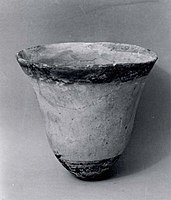

Ubaid culture is characterized by large unwalled village settlements, multi-roomed rectangular mud-brick houses and the appearance of the first temples of public architecture in Mesopotamia, with a growth of a two tier settlement hierarchy of centralized large sites of more than 10 hectares surrounded by smaller village sites of less than 1 hectare. Domestic equipment included a distinctive fine quality buff or greenish colored pottery decorated with geometric designs in brown or black paint. Tools such as sickles were often made of hard fired clay in the south, while in the north stone and sometimes metal were used. Villages thus contained specialised craftspeople, potters, weavers and metalworkers, although the bulk of the population were agricultural labourers, farmers and seasonal pastoralists.

During the Ubaid Period (5000–4000 BC), the movement towards urbanization began. "Agriculture and animal husbandry [domestication] were widely practiced in sedentary communities".[34] There were also tribes that practiced domesticating animals as far north as Turkey, and as far south as the Zagros Mountains.[34] The Ubaid period in the south was associated with intensive irrigated hydraulic agriculture, and the use of the plough, both introduced from the north, possibly through the earlier Choga Mami, Hadji Muhammed and Samarra cultures.

The Ubaid period as a whole, based upon the analysis of grave goods, was one of increasingly polarized social stratification and decreasing egalitarianism. Bogucki describes this as a phase of "Trans-egalitarian" competitive households, in which some fall behind as a result of downward social mobility. Morton Fried and Elman Service have hypothesised that Ubaid culture saw the rise of an elite class of hereditary chieftains, perhaps heads of kin groups linked in some way to the administration of the temple shrines and their granaries, responsible for mediating intra-group conflict and maintaining social order. It would seem that various collective methods, perhaps instances of what Thorkild Jacobsen called primitive democracy, in which disputes were previously resolved through a council of one's peers, were no longer sufficient for the needs of the local community.

Ubaid culture originated in the south, but still has clear connections to earlier cultures in the region of middle Iraq. The appearance of the Ubaid folk has sometimes been linked to the so-called Sumerian problem, related to the origins of Sumerian civilisation. Whatever the ethnic origins of this group, this culture saw for the first time a clear tripartite social division between intensive subsistence peasant farmers, with crops and animals coming from the north, tent-dwelling nomadic pastoralists dependent upon their herds, and hunter-fisher folk of the Arabian littoral, living in reed huts.

Stein and Özbal describe the Near East oecumene that resulted from Ubaid expansion, contrasting it to the colonial expansionism of the later Uruk period. "A contextual analysis comparing different regions shows that the Ubaid expansion took place largely through the peaceful spread of an ideology, leading to the formation of numerous new indigenous identities that appropriated and transformed superficial elements of Ubaid material culture into locally distinct expressions."[35]

The earliest evidence for sailing has been found in Kuwait indicating that sailing was known by the Ubaid 3 period.[9]

There is some evidence of warfare during the Ubaid period although it is extremely rare. The "Burnt Village" at Tell Sabi Abyad could be suggestive of destruction during war but it could also have been due to other causes, such as wildfire or accident. Ritual burning is also possible since the bodies inside were already dead by the time they were burned. A mass grave at Tepe Gawra contained 24 bodies apparently buried without any funeral rituals, possibly indicating it was a mass grave from violence. Copper weapons were also present in the form of arrow heads and sling bullets, although these could have been used for other purpose; two clay pots recovered from the era have decorations showing arrows used for the purpose of hunting. A copper axe head was made in the late Ubaid period, which could have been a tool or a weapon.[36]

![Stamp seal with Master of Animals motif; c. 4000 BC; Tell Tello; Louvre Museum AO 15388[37][38][39]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b6/Stamp_seal_with_Master_of_Animals_motif%2C_Tello%2C_ancient_Girsu%2C_End_of_Ubaid_period%2C_Louvre_Museum_AO14165_%28detail%29.jpg/193px-Stamp_seal_with_Master_of_Animals_motif%2C_Tello%2C_ancient_Girsu%2C_End_of_Ubaid_period%2C_Louvre_Museum_AO14165_%28detail%29.jpg)