Zengid dynasty

The Zengid or Zangid dynasty (Arabic: الدولة الزنكية romanized: al-Dawla al-Zinkia) was an Atabegate of the Seljuk Empire created in 1127.[3] It formed a Turkoman dynasty of Sunni Muslim faith,[4] which ruled parts of the Levant and Upper Mesopotamia, and eventually seized control of Egypt in 1169.[5][6] In 1174 the Zengid state extended from Tripoli to Hamadan and from Yemen to Sivas.[7][8] Imad ad-Din Zengi was the first ruler of the dynasty.

Zengid Stateالدولة الزنكية

Atabegate of the Seljuk Empire (1127-1194)

Emirate (1194-1250)

Oghuz Turkic

Arabic (numismatics)[2]

Imad ad-Din Zengi (first)

Mahmud Al-Malik Al-Zahir (last reported)

1127

1250

The Zengid Atabegate became famous in the Islamic world for its successes against the Crusaders, and for being the Atabegate from which Saladin originated.[9] Following the demise of the Seljuk dynasty in 1194, the Zengids persisted for several decades as one of the "Seljuq successor-states" until 1250.[10]

The area including Syria, Jazira and Iraq saw an "explosion of figural art" from the 12th to 13th centuries, particularly in the areas of decorative art and illustrated manuscripts.[83][84] This occurred despite religious condemnations against the depiction of living creatures, on the grounds that "it implies a likeness to the creative activity of God".[83]

The origins of this new pictorial tradition are uncertain, but Arabic illustrated manuscripts such as the Maqamat al-Hariri shared many characteristics with Christian Syriac illustrated manuscripts, such as Syriac Gospels (British Library, Add. 7170).[85] This synthesis seems to point to a common pictorial tradition that existed since circa 1180 CE in the region, which was highly influenced by Byzantine art.[85][86]

The manuscript Kitâb al-Diryâq (Arabic: كتاب الدرياق, romanized: Kitāb al-diryāq, "The Book of Theriac"), or Book of anditodes of pseudo-Galen, is a medieval manuscript allegedly based on the writings of Galen ("pseudo-Galen"). It describes the use of Theriac, an ancient medicinal compound initially used as a cure for the bites of poisonous snakes. Two editions are extant, adorned with beautiful miniatures revealing of the social context at the time of their publication.[87] The earliest manuscript was published in 1198-1199 CE in Mosul or the Jazira region, and is now in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (MS. Arabe 2964).[87][88]

The Kitab al-Aghani was created in 1218-1219 in Mosul at the time of the Zengid atabegate of Badr al-Din Lu'lu' (40 years old at the time), and has several frontispieces richly illustrated with court scenes.[26]

The Zengids are known for numerous constructions from Syria to northern Iraq. The Citadel of Aleppo was fortified by the Zengids during the Crusades. Imad ad-Din Zengi, followed by his son Nur ad-Din (ruled 1147–1174), unified Aleppo and Damascus and held back the Crusaders from their repeated assaults on the cities. In addition to his many works in both Aleppo and Damascus, Nur ad-Din rebuilt the Aleppo city walls and fortified the citadel. Arab sources report that he also made several other improvements, such as a high, brick-walled entrance ramp, a palace, and a racecourse likely covered with grass. Nur ad-Din additionally restored or rebuilt the two mosques and donated an elaborate wooden mihrab (prayer niche) to the Mosque of Abraham. Several famous crusaders were imprisoned in the citadel, among them Count of Edessa, Joscelin II, who died there, Raynald of Châtillon, and the King of Jerusalem, Baldwin II, who was held for two years.[93]

The Nur al-Din Madrasa is a funerary madrasa in Damascus, Syria. It was built in 1167 by Nūr ad-Dīn Zangī, atabeg of Syria, who is buried there. The complex includes a mosque, a madrasa, and the mausoleum of the founder. It was the first such complex to be built in Damascus.[94][95] The Nur al-Din Bimaristan is a large Muslim medieval bimaristan ("hospital") in Damascus, Syria. It was built and named after the Nur ad-Din Zangi in 1154.[96]

The Great Mosque of al-Nuri, Mosul was also built by Nur ad-Din Zangi in 1172–1173, shortly before his death.[97][98]

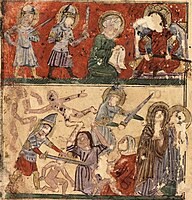

Christianity in the Middle East continued to suffer a general decline within a context of Arabization and Islamization, as well as the conflict of the Crusades.[100] Still, Syriac Christianity remained active under the Zengids, and even went through a phase of "Syriac Renaissance" in which discriminatory rules against Christians were lifted, especially after the death of the conservative Nur al-Din Zengi in 1174.[100] Several important Christian manuscripts were created in Mosul during the late Zengid period, especially under the atabagate of Badr al-Din Lu'lu' (1211-1234), and later during his independent reign (1234-1259).[101] One of them, the Jacobite-Syrian Lectionary of the Gospels, was created at the Mar Mattai Monastery 20 kilometers northeast of the city of Mosul, c.1220 (Vatican Library, Ms. Syr. 559).[102] This Gospel, with its depiction of many military figures in armour, is considered as a useful reference of the military technologies of classical Islam during the period.[103] Another such gospel is Ms. Additional 7170, British Library, also created circa 1220 in the Mosul region.[101]

![A Qur'an in the name of Zengid ruler Qutb ad-Din Muhammad (1197–1219). (Khalili QUR 497)[89]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/99/Khalili_Collection_Islamic_Art_qur_0497_fol_1b-2a.jpg/160px-Khalili_Collection_Islamic_Art_qur_0497_fol_1b-2a.jpg)

![Kitâb al-Diryâq, 1198-1199, folio 24. Royal court detail, ruler in Turkic dress, wearing the sharbush hat.[90]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1a/Kitab_al-Dariyaq%2C_folio_24_%28royal_court_detail%29.jpg/160px-Kitab_al-Dariyaq%2C_folio_24_%28royal_court_detail%29.jpg)

![Figures in Turkic dress, with aqbiya turkiyya coat, tiraz armbands, boots and sharbush hat. Kitāb al-Diryāq, Jazira, 1198-1199 CE.[91]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/73/Kitab_al-Diryaq_BNF_View_11_%28detail%29.jpg/160px-Kitab_al-Diryaq_BNF_View_11_%28detail%29.jpg)

![Warrior wearing the sharbush, a three-quarters length robe, and boots. De Materia Medica of Dioscorides, Iraq, 1224. Harvard Art Museums.[92]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b2/Warrior_with_the_Plant_Kestron%2C_De_Materia_Medica_of_Dioscorides%2C_Iraq_1224._Harvard_Art_Museums.jpg/108px-Warrior_with_the_Plant_Kestron%2C_De_Materia_Medica_of_Dioscorides%2C_Iraq_1224._Harvard_Art_Museums.jpg)

![Zengid Ain Diwar Bridge. Built under Qutb al-Din Mawdud, from 1146 to 1163 CE. Cizre.[99]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0a/Remains_of_the_Tigris_bridge_near_Ayn_D%C4%ABw%C4%81r_viewed_from_downriver_a_few_years_before_the_outbreak_of_the_First_World_War%2C_at_a_time_when_the_Tigris_was_in_flood_%28The_Gertrude_Bell_Archive%2C_Newcastle_University%29.jpg/160px-thumbnail.jpg)

![Miniature of a Syriac gospel from around Mosul, c. 1220 (BL Ms. 7170). Badr al-Din Lu'lu' was tolerant of Christian religion.[101]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/53/Ms._Additional_7170%2C_British_Library_156v_Christ_resurrected_%28fine%29.jpg/160px-Ms._Additional_7170%2C_British_Library_156v_Christ_resurrected_%28fine%29.jpg)