1844 United States presidential election

The 1844 United States presidential election was the 15th quadrennial presidential election, held from Friday, November 1 to Wednesday, December 4, 1844. Democrat James K. Polk narrowly defeated Whig Henry Clay in a close contest turning on the controversial issues of slavery and the annexation of the Republic of Texas. This is the only election in which both major party nominees served as Speaker of the House at one point, and the first in which neither candidate held elective office at the time.

275 electoral votes of the Electoral College

138 electoral votes needed to win

President John Tyler's pursuit of Texas annexation divided both major parties. Annexation would geographically expand American slavery. It also risked war with Mexico while the United States engaged in sensitive possession and boundary negotiations with the Great Britain, which controlled Canada, over Oregon. Texas annexation thus posed both domestic and foreign policy risks. Both major parties had wings in the North and the South, but the possibility of the expansion of slavery threatened a sectional split in each party. Expelled by the Whig Party after vetoing key Whig legislation and lacking a firm political base, Tyler hoped to use the annexation of Texas to win the presidency as an independent or at least to have decisive, pro-Texas influence over the election.

The early leader for the Democratic nomination was former President Martin Van Buren, but his opposition to the annexation of Texas damaged his candidacy. Opposition from former President Andrew Jackson and most Southern delegations, plus a nomination rule change specifically aimed to block him, prevented Van Buren from winning the necessary two-thirds vote of delegates to the 1844 Democratic National Convention. The convention instead chose James K. Polk, former Governor of Tennessee and Speaker. He was the first successful dark horse for the presidency. Polk ran on a platform embracing popular commitment to expansion, often referred to as Manifest Destiny. Tyler dropped out of the race and endorsed Polk. The Whigs nominated Henry Clay, a famous, long-time party leader who was the early favorite but who conspicuously waffled on Texas annexation. Though a Southerner from Kentucky and a slave owner, Clay chose to focus on the risks of annexation while claiming not to oppose it personally. His awkward, repeated attempts to adjust and finesse his position on Texas confused and alienated voters, contrasting negatively with Polk's consistent clarity.

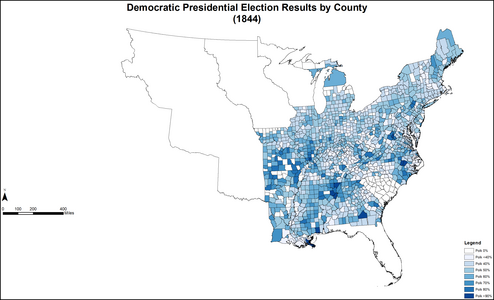

Polk successfully linked the dispute with Britain over Oregon with the Texas issue. The Democratic nominee thus united anti-slavery Northern expansionists, who demanded Oregon, with pro-slavery Southern expansionists who demanded Texas. In the national popular vote, Polk beat Clay by fewer than 40,000 votes, a margin of 1.4%. James G. Birney of the anti-slavery Liberty Party won 2.3% of the vote. As President, Polk completed American annexation of Texas, which was the proximate cause of the Mexican–American War.

Background[edit]

Gag rule and Texas annexation controversies[edit]

Whigs and Democrats embarked upon their campaigns during the climax of the congressional gag rule controversies in 1844, which prompted Southern congressmen to suppress northern petitions to end the slave trade in the District of Columbia.[3][4] Anti-annexation petitions to Congress sent from northern anti-slavery forces, including state legislatures, were similarly suppressed.[5][6] Intra-party sectional compromises and maneuvering on slavery politics during these divisive debates placed significant strain on the northern and southern wings that comprised each political organization.[7] The question as to whether the institution of slavery and its aristocratic principles of social authority were compatible with democratic republicanism was becoming "a permanent issue in national politics".[8][9]

In 1836, a portion of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas declared its independence to form the Republic of Texas. Texans, mostly American immigrants from the Deep South, many of whom owned slaves, sought to bring their republic into the Union as a state. At first, the subject of annexing Texas to the United States was shunned by both major American political parties.[10] Although they recognized Texas sovereignty, Presidents Andrew Jackson (1829–1837) and Martin Van Buren (1837–1841) declined to pursue annexation.[11][12] The prospect of bringing another slave state into the Union was fraught with problems.[13] Both major parties – the Democrats and Whigs – viewed Texas statehood as something "not worth a foreign war [with Mexico]" or the "sectional combat" that annexation would provoke in the United States.[14][15]

Tyler–Texas treaty[edit]

The incumbent President John Tyler, formerly vice-president, had assumed the presidency upon the death of William Henry Harrison in 1841. Tyler, a Whig in name only,[16] emerged as a states' rights advocate committed to slavery expansion in defiance of Whig principles.[17][18] After he vetoed the Whig domestic legislative agenda, he was expelled from his own party on September 13, 1841.[19][20] Politically isolated, but unencumbered by party restraints,[21] Tyler aligned himself with a small faction of Texas annexationists[22] in a bid for election to a full term in 1844.[23][24][25]

Tyler became convinced that Great Britain was encouraging a Texas–Mexico rapprochement that might lead to slave emancipation in the Texas republic.[26][27] Accordingly, he directed Secretary of State Abel P. Upshur of Virginia to initiate, then relentlessly pursue, secret annexation talks[28][29] with Texas minister to the United States Isaac Van Zandt, beginning on October 16, 1843.[30]

Tyler submitted his Texas-U.S. treaty for annexation to the U.S. Senate, delivered April 22, 1844, where a two-thirds majority was required for ratification.[31][32] The newly appointed Secretary of State John C. Calhoun of South Carolina (assuming his post March 29, 1844)[33] included a document known as the Packenham Letter with the Tyler bill that was calculated to inject a sense of crisis in Southern Democrats of the Deep South.[34] In it, he characterized slavery as a social blessing and the acquisition of Texas as an emergency measure necessary to safeguard the "peculiar institution" in the United States.[35][36] In doing so, Tyler and Calhoun sought to unite the South in a crusade that would present the North with an ultimatum: support Texas annexation or lose the South.[37] Anti-slavery Whigs considered Texas annexation particularly egregious, since Mexico had outlawed slavery in Coahuila y Tejas in 1829, before Texas independence had been declared.

The 1844 presidential campaigns evolved within the context of this struggle over Texas annexation, which was tied to the question of slavery expansion and national security.[38][39] All candidates in the 1844 presidential election had to declare a position on this explosive issue.[40][41]