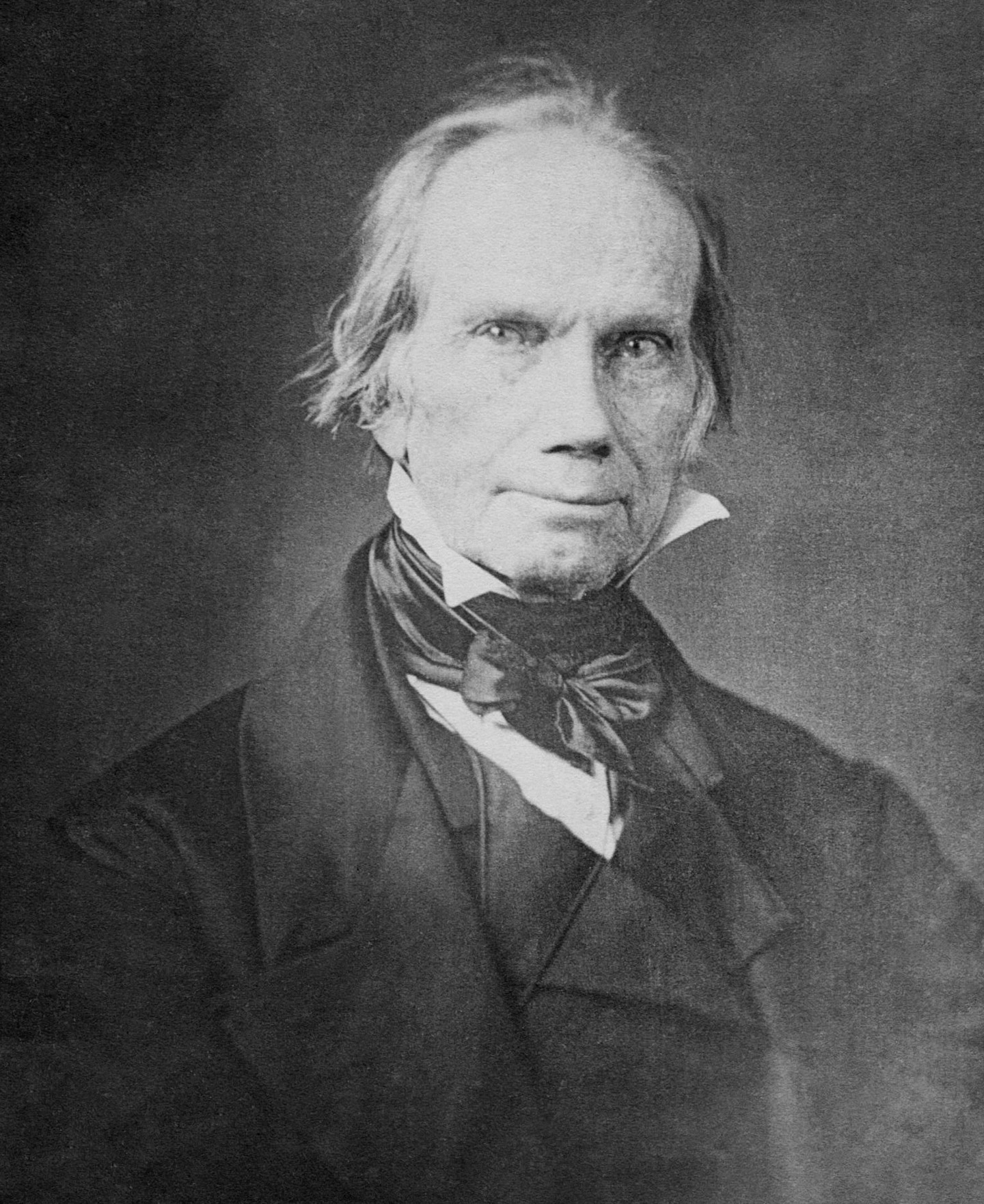

Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777 – June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. He was the seventh House speaker as well as the ninth secretary of state. He unsuccessfully ran for president in the 1824, 1832, and 1844 elections. He helped found both the National Republican Party and the Whig Party. For his role in defusing sectional crises, he earned the appellation of the "Great Compromiser" and was part of the "Great Triumvirate" of Congressmen, alongside fellow Whig Daniel Webster and Democrat John C. Calhoun.

For other people named Henry Clay, see Henry Clay (disambiguation).

Henry Clay

Langdon Cheves

Joseph H. Hawkins

2nd district (1813–1814)

5th district (1811–1813)

April 12, 1777

Hanover County, Virginia, U.S.

June 29, 1852 (aged 75)

Washington, D.C., U.S.

Democratic-Republican (1797–1825)

National Republican (1825–1833)

Whig (1833–1852)

Clay was born in Virginia, in 1777, and began his legal career in Lexington, Kentucky, in 1797. As a member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Clay won election to the Kentucky state legislature in 1803 and to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1810. He was chosen as Speaker of the House in early 1811 and, along with President James Madison, led the United States into the War of 1812 against Great Britain. In 1814, he helped negotiate the Treaty of Ghent, which brought an end to the War of 1812, and then after the war, Clay returned to his position as Speaker of the House and developed the American System, which called for federal infrastructure investments, support for the national bank, and high protective tariff rates. In 1820 he helped bring an end to a sectional crisis over slavery by leading the passage of the Missouri Compromise. Clay finished with the fourth-most electoral votes in the multi-candidate 1824-1825 presidential election and used his position as speaker to help John Quincy Adams win the contingent election held to select the president. President Adams then appointed Clay to the prestigious position of secretary of state; as a result, critics alleged that the two had agreed to a "corrupt bargain". Despite receiving support from Clay and other National Republicans, Adams was defeated by Democrat Andrew Jackson in the 1828 presidential election. Clay won election to the Senate in 1831 and ran as the National Republican nominee in the 1832 presidential election, but he was defeated decisively by President Jackson. After the 1832 election, Clay helped bring an end to the nullification crisis by leading passage of the Tariff of 1833. During Jackson's second term, opponents of the president including Clay, Webster, and William Henry Harrison created the Whig Party, and through the years, Clay became a leading congressional Whig.

Clay sought the presidency in the 1840 election but was passed over at the Whig National Convention by Harrison. When Harrison died and his vice president ascended to office, Clay clashed with Harrison's successor, John Tyler, who broke with Clay and other congressional Whigs after taking office upon Harrison's death in 1841. Clay resigned from the Senate in 1842 and won the 1844 Whig presidential nomination, but he was narrowly defeated in the general election by Democrat James K. Polk, who made the annexation of the Republic of Texas his top issue. Clay strongly criticized the subsequent Mexican–American War and sought the Whig presidential nomination in 1848 but was passed over in favor of General Zachary Taylor who went on to win the election. After returning to the Senate in 1849, Clay played a key role in passing the Compromise of 1850, which postponed a crisis over the status of slavery in the territories. Clay was one of the most important and influential political figures of his era.[1]

Early life[edit]

Henry Clay was born on April 12, 1777, at the Clay homestead in Hanover County, Virginia.[2] He was the seventh of nine children born to the Reverend John Clay and Elizabeth (née Hudson) Clay.[3] Almost all of Henry's older siblings died before adulthood.[4] His father, a Baptist minister nicknamed "Sir John", died in 1781, leaving Henry and his brothers two slaves each; he also left his wife 18 slaves and 464 acres (188 ha) of land.[5] Clay was of entirely English descent;[6] his ancestor, John Clay, settled in Virginia in 1613.[7] The Clay family became a well-known political family including three other US senators, numerous state politicians, and Clay's cousin Cassius Clay, a prominent anti-slavery activist active in the mid-19th century.[8]

The British raided Clay's home shortly after the death of his father, leaving the family in a precarious economic position.[9] However, the widow Elizabeth Clay married Captain Henry Watkins, a successful planter and cousin to John Clay.[10] Elizabeth would have seven more children with Watkins, bearing a total of sixteen children.[11] Watkins became a kind and supportive stepfather and Clay had a very good relationship with him.[12] After his mother's remarriage, the young Clay remained in Hanover County, where he learned how to read and write.[10] In 1791, Watkins moved the family to Kentucky, joining his brother in the pursuit of fertile new lands in the West. However, Clay did not follow, as Watkins secured his temporary employment in a Richmond emporium, with the promise that Clay would receive the next available clerkship at the Virginia Court of Chancery.[13]

After Clay had worked at the Richmond emporium for a year, he obtained a clerkship that had become available at the Virginia Court of Chancery. Clay adapted well to his new role, and his handwriting earned him the attention of College of William & Mary professor George Wythe, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, mentor of Thomas Jefferson, and judge on Virginia's High Court of Chancery.[14] Hampered by a crippled hand, Wythe chose Clay as his secretary and amanuensis, a role in which Clay would remain for four years.[15] Wythe had a powerful effect on Clay's worldview, with Clay embracing Wythe's belief that the example of the United States could help spread human freedom around the world.[16] Wythe subsequently arranged a position for Clay with Virginia attorney general Robert Brooke, with the understanding that Brooke would finish Clay's legal studies.[17] After completing his studies under Brooke, Clay was admitted to the Virginia Bar in 1797.[18]

Speaker of the House[edit]

Election and leadership[edit]

The 1810–1811 elections produced many young, anti-British members of Congress who, like Clay, supported going to war with Great Britain. Buoyed by the support of fellow war hawks, Clay was elected Speaker of the House for the 12th Congress.[59] At 34, he was the youngest person to become speaker, a distinction he held until 1839, when 30-year-old Robert M. T. Hunter took office.[60] He was also the first of only two new members elected speaker to date,[b] the other being William Pennington in 1860.[61]

Between 1810 and 1824, Clay was elected to seven terms in the House.[62] His tenure was interrupted from 1814 to 1815 when he was a commissioner to peace talks with the British in Ghent, United Netherlands to end the War of 1812, and from 1821 to 1823, when he left Congress to rebuild his family's fortune in the aftermath of the Panic of 1819.[63] Elected speaker six times, Clay's cumulative tenure in office of 10 years, 196 days, is the second-longest, surpassed only by Sam Rayburn.[64]

As speaker, Clay wielded considerable power in making committee appointments, and like many of his predecessors he assigned his allies to important committees. Clay was exceptional in his ability to control the legislative agenda through well-placed allies and the establishment of new committees and departed from precedent by frequently taking part in floor debates.[65] Yet he also gained a reputation for personal courteousness and fairness in his rulings and committee appointments.[66] Clay's drive to increase the power of the office of speaker was aided by President James Madison, who deferred to Congress in most matters.[67] John Randolph, a member of the Democratic-Republican Party but also a member of the "tertium quids" group that opposed many federal initiatives, emerged as a prominent opponent of Speaker Clay.[68] While Randolph frequently attempted to obstruct Clay's initiatives, Clay became a master of parliamentary maneuvers that enabled him to advance his agenda even over the attempted obstruction by Randolph and others.[69][c]

Legacy[edit]

Historical reputation[edit]

Clay's Whig Party collapsed four years after his death, but Clay cast a long shadow over the generation of political leaders that presided over the Civil War. Mississippi Senator Henry S. Foote stated his opinion that "had there been one such man in the Congress of the United States as Henry Clay in 1860–1861 there would, I feel sure, have been no civil war".[259][260] Clay's protege and fellow Kentuckian, John J. Crittenden, attempted to keep the Union together with the formation of the Constitutional Union Party and the proposed Crittenden Compromise. Though Crittenden's efforts were unsuccessful, Kentucky remained in the Union during the Civil War, reflecting in part Clay's continuing influence.[261] Abraham Lincoln was a great admirer of Clay, saying he was "my ideal of a great man." Lincoln wholeheartedly supported Clay's economic programs and, prior to the Civil War, held similar stances about slavery and the Union.[262] Some historians have argued that a Clay victory in the 1844 election would have prevented both the Mexican-American War and the American Civil War.[263]