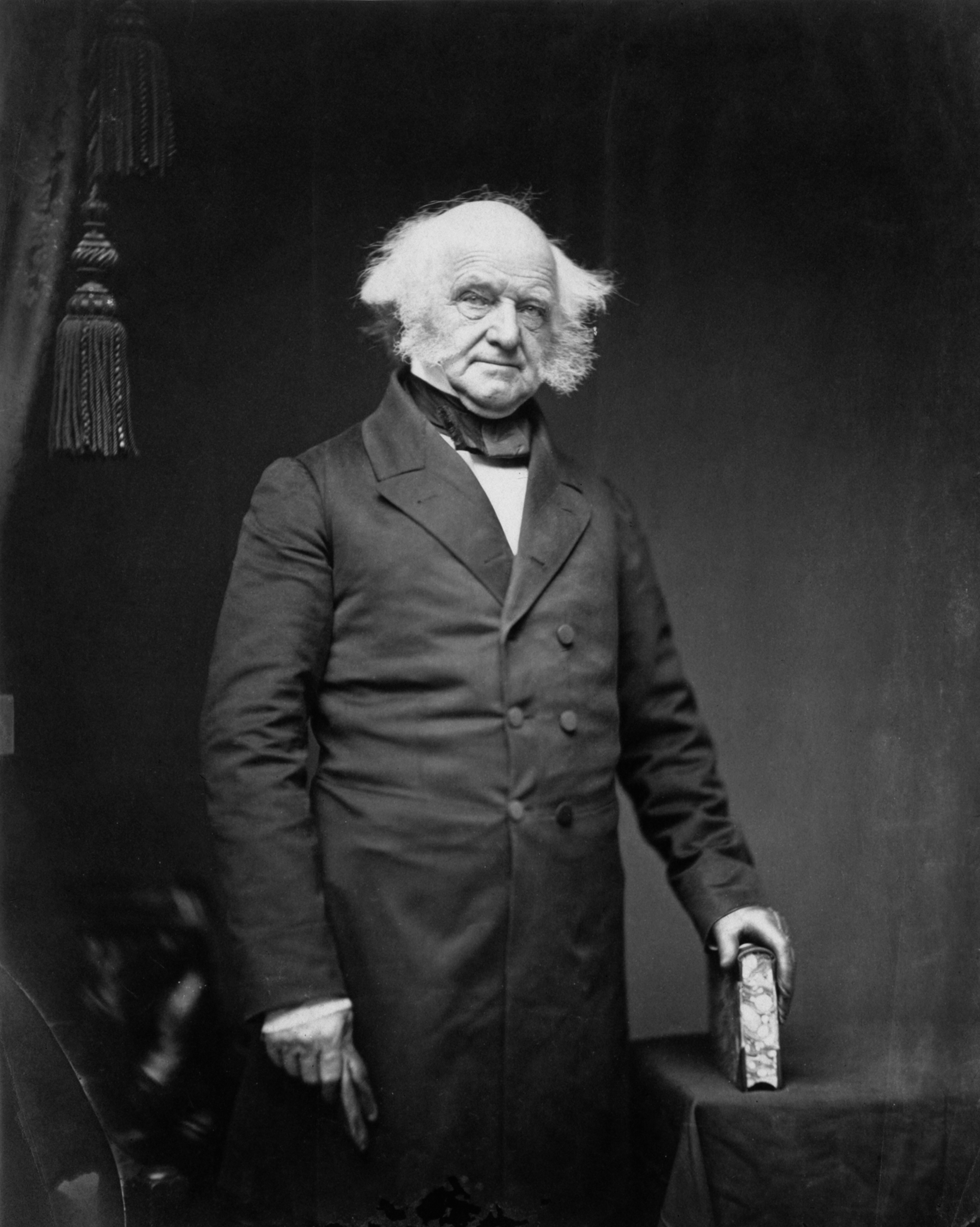

Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren (/væn ˈbjʊərən/ van BURE-ən; Dutch: Maarten van Buren [ˈmaːrtə(n) vɑm ˈbyːrə(n)] ⓘ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer, diplomat, and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party, he served as New York's attorney general and U.S. senator, then briefly as the ninth governor of New York before joining Andrew Jackson's administration as the tenth United States secretary of state, minister to Great Britain, and ultimately the eighth vice president when named Jackson's running mate for the 1832 election. Van Buren won the presidency in 1836 against divided Whig opponents. Van Buren lost re-election in 1840, and failed to win the Democratic nomination in 1844. Later in his life, Van Buren emerged as an elder statesman and an important anti-slavery leader who led the Free Soil Party ticket in the 1848 presidential election.

"Van Buren" redirects here. For other uses, see Van Buren (disambiguation).

Martin Van Buren

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson

Aaron Vail (acting)

Andrew Jackson

Enos T. Throop

- William C. Bouck

- John I. Miller

- Tilly Lynde

James Vanderpoel

July 24, 1862 (aged 79)

Kinderhook, New York, U.S.

- Democratic-Republican (1799–1825)

- Democratic (1825–1848, from 1852)

- Free Soil (1848–1852)

5 ft 6 in (1.68 m)[1]

5, including Abraham II and John

- Abraham Van Buren (father)

- Politician

- lawyer

Van Buren was born in Kinderhook, New York, where most residents were of Dutch descent and spoke Dutch as their primary language; he is the only president to have spoken English as a second language. Trained as a lawyer, he entered politics as a member of the Democratic-Republican Party, won a seat in the New York State Senate, and was elected to the United States Senate in 1821. As the leader of the Bucktails faction, Van Buren emerged as the most influential politician from New York in the 1820s and established a political machine known as the Albany Regency. He ran successfully for governor of New York to support Andrew Jackson's candidacy in the 1828 presidential election but resigned shortly after Jackson was inaugurated so he could accept appointment as Jackson's secretary of state. In the cabinet, Van Buren was a key Jackson advisor and built the organizational structure for the coalescing Democratic Party. He ultimately resigned to help resolve the Petticoat affair and briefly served as ambassador to Great Britain. At Jackson's behest, the 1832 Democratic National Convention nominated Van Buren for vice president, and he took office after the Democratic ticket won the 1832 presidential election.

With Jackson's strong support and the organizational strength of the Democratic Party, Van Buren successfully ran for president in the 1836 presidential election. However, his popularity soon eroded because of his response to the Panic of 1837, which centered on his Independent Treasury system, a plan under which the federal government of the United States would store its funds in vaults rather than in banks; more conservative Democrats and Whigs in Congress ultimately delayed his plan from being implemented until 1840. His presidency was further marred by the costly Second Seminole War and his refusal to admit Texas to the Union as a slave state. In 1840, Van Buren lost his re-election bid to William Henry Harrison. While Van Buren is praised for anti-slavery stances, in historical rankings, historians and political scientists often rank Van Buren as an average or below-average U.S. president, due to his handling of the Panic of 1837.

Van Buren was initially the leading candidate for the Democratic Party's nomination again in 1844, but his continued opposition to the annexation of Texas angered Southern Democrats, leading to the nomination of James K. Polk. Growing opposed to slavery, Van Buren was the newly formed Free Soil Party's presidential nominee in 1848, and his candidacy helped Whig nominee Zachary Taylor defeat Democrat Lewis Cass. Worried about sectional tensions, Van Buren returned to the Democratic Party after 1848 but was disappointed with the pro-southern presidencies of Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan. During the American Civil War, Van Buren was a War Democrat who supported the policies of President Abraham Lincoln, a Republican. He died of asthma at his home in Kinderhook in 1862, aged 79.

Post-presidency (1841–1862)[edit]

Election of 1844[edit]

On the expiration of his term, Van Buren returned to his estate of Lindenwald in Kinderhook.[204] He continued to closely watch political developments, including the battle between the Whig alliance of the Great Triumvirate and President John Tyler, who took office after Harrison's death in April 1841.[205] Though undecided on another presidential run, Van Buren made several moves calculated to maintain his support, including a trip to the Southern United States and the Western United States during which he met with Jackson, former Speaker of the House James K. Polk, and others.[206] President Tyler, James Buchanan, Levi Woodbury, and others loomed as potential challengers for the 1844 Democratic nomination, but it was Calhoun who posed the most formidable obstacle.[207]

Van Buren remained silent on major public issues like the debate over the Tariff of 1842, hoping to arrange for the appearance of a draft movement for his presidential candidacy.[208] Tyler made the annexation of Texas his chief foreign policy goal, and many Democrats, particularly in the South, were anxious to quickly complete it.[209] After an explosion on the USS Princeton killed Secretary of State Abel P. Upshur in February 1844, Tyler brought Calhoun into his cabinet to direct foreign affairs.[210] Like Tyler, Calhoun pursued the annexation of Texas to upend the presidential race and to extend slavery into new territories.[211]

Shortly after taking office, Calhoun negotiated an annexation treaty between the United States and Texas.[212] Van Buren had hoped he would not have to take a public stand on annexation, but as the Texas question came to dominate U.S. politics, he decided to make his views on the issue public.[213] Though he believed that his public acceptance of annexation would likely help him win the 1844 Democratic nomination, Van Buren thought that annexation would inevitably lead to an unjust war with Mexico.[214] In a public letter published shortly after Henry Clay also announced his opposition to the annexation treaty, Van Buren articulated his views on the Texas question.[215]

Van Buren's opposition to immediate annexation cost him the support of many pro-slavery Democrats.[216] In the weeks before the 1844 Democratic National Convention, Van Buren's supporters anticipated that he would win a majority of the delegates on the first presidential ballot, but would not be able to win the support of the required two-thirds of delegates.[217] Van Buren's supporters attempted to prevent the adoption of the two-thirds rule, but several Northern delegates joined with Southern delegates in implementing the two-thirds rule for the 1844 convention.[218] Van Buren won 146 of the 266 votes on the first presidential ballot, with only 12 of his votes coming from Southern states.[209]

Senator Lewis Cass won much of the remaining vote, and he gradually picked up support on subsequent ballots until the convention adjourned for the day.[219] When the convention reconvened and held another ballot, James K. Polk, who shared many of Van Buren's views but favored immediate annexation, won 44 votes.[220] On the ninth ballot, Van Buren's supporters withdrew his name from consideration, and Polk won the nomination.[221] Although angered that his opponents had denied him the nomination, Van Buren endorsed Polk in the interest of party unity.[222] He also convinced Silas Wright to run for Governor of New York so that the popular Wright could help boost Polk in the state.[223] Wright narrowly defeated Whig nominee Millard Fillmore in the 1844 gubernatorial election, and Wright's victory in the state helped Polk narrowly defeat Henry Clay in the 1844 presidential election.[224]

After taking office, Polk used George Bancroft as an intermediary to offer Van Buren the ambassadorship to London. Van Buren declined, partly because he was upset with Polk over the treatment the Van Buren delegates had received at the 1844 convention, and partly because he was content in his retirement.[225] Polk also consulted Van Buren in the formation of his cabinet, but offended Van Buren by offering to appoint a New Yorker only to the lesser post of Secretary of War, rather than as Secretary of State or Secretary of the Treasury.[226] Other patronage decisions also angered Van Buren and Wright, and they became permanently alienated from the Polk administration.[227]

Legacy[edit]

Historical reputation[edit]

Van Buren's most lasting achievement was as a political organizer who built the Democratic Party and guided it to dominance in the Second Party System,[257] and historians have come to regard Van Buren as integral to the development of the American political system.[30] According to historian Robert V. Remini: