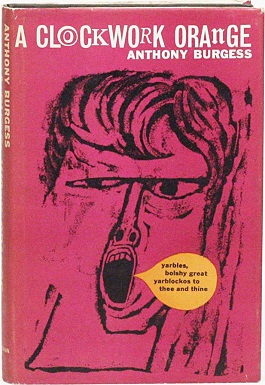

A Clockwork Orange (novel)

A Clockwork Orange is a dystopian satirical black comedy novella by English writer Anthony Burgess, published in 1962. It is set in a near-future society that has a youth subculture of extreme violence. The teenage protagonist, Alex, narrates his violent exploits and his experiences with state authorities intent on reforming him.[1] The book is partially written in a Russian-influenced argot called "Nadsat", which takes its name from the Russian suffix that is equivalent to '-teen' in English.[2] According to Burgess, the novel was a jeu d'esprit written in just three weeks.[3]

Author

Barry Trengove

United Kingdom

English

1962 (William Heinemann, UK)

192 pages (hardback edition)

176 pages (paperback edition)

In 2005, A Clockwork Orange was included on Time magazine's list of the 100 best English-language novels written since 1923,[4] and it was named by Modern Library and its readers as one of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century.[5] The original manuscript of the book has been kept at McMaster University's William Ready Division of Archives and Research Collections in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada since the institution purchased the documents in 1971.[6]

It is considered one of the most influential dystopian books.

In 2022, the novel was included on the "Big Jubilee Read" list of 70 books by Commonwealth authors selected to celebrate the Platinum Jubilee of Elizabeth II.[7]

Plot summary[edit]

Part 1: Alex's world[edit]

Alex is a 15-year-old gang leader living in a near-future dystopian city. His friends ("droogs" in the novel's Anglo-Russian slang, "Nadsat") and fellow gang members are Dim, a slow-witted bruiser, who is the gang's muscle; Georgie, an ambitious second-in-command; and Pete, who mostly plays along as the droogs indulge their taste for "ultra-violence" (random, violent mayhem). Characterised as a sociopath and hardened juvenile delinquent, Alex is also intelligent, quick-witted, and enjoys classical music; he is particularly fond of Beethoven, whom he calls "Lovely Ludwig Van".

The droogs sit in their favourite hangout, the Korova Milk Bar, drinking "milk-plus" (milk laced with the customer's drug of choice) to prepare for a night of ultra-violence. They assault a scholar walking home from the public library; rob a shop, leaving the owner and his wife bloodied and unconscious; beat up a beggar; then scuffle with a rival gang. Joyriding through the countryside in a stolen car, they break into an isolated cottage and terrorise the young couple living there, beating the husband and gang-raping his wife. The husband is a writer working on a manuscript entitled A Clockwork Orange, and Alex contemptuously reads out a paragraph that states the novel's main theme before shredding the manuscript. At the Korova, Alex strikes Dim for his crude response to a woman's singing of an operatic passage, and strains within the gang become apparent. At home in his parents' flat, Alex plays classical music at top volume, which he describes as giving him orgasmic bliss before falling asleep.

Alex feigns illness to his parents to stay out of school the next day. Following an unexpected visit from P.R. Deltoid, his "post-corrective adviser", Alex visits a record store, where he meets two pre-teen girls. He invites them back to the flat, where he drugs and rapes them. That night after a nap, Alex finds his droogs in a mutinous mood, waiting downstairs in the torn-up and graffitied lobby. Georgie challenges Alex for leadership of the gang, demanding that they focus on higher-value targets in their robberies. Alex quells the rebellion by slashing Dim's hand and fighting with Georgie, then soothes the gang by agreeing to Georgie's plan to rob the home of a wealthy elderly woman. Alex breaks in and knocks the woman unconscious, but when he hears sirens and opens the door to flee, Dim strikes him as revenge for the earlier fight. The gang abandons Alex on the front step to be arrested by the police; while in custody, he learns that the woman has died from her injuries.

Omission of the final chapter in the US[edit]

The book has three parts, each with seven chapters. Burgess has stated that the total of 21 chapters was an intentional nod to the age of 21 being recognised as a milestone in human maturation.[8] The 21st chapter was omitted from the editions published in the United States prior to 1986.[9] In the introduction to the updated American text (these newer editions include the missing 21st chapter), Burgess explains that when he first brought the book to an American publisher, he was told that US audiences would never go for the final chapter, in which Alex sees the error of his ways, decides he has lost his taste for violence and resolves to turn his life around.

At the American publisher's insistence, Burgess allowed its editors to cut the redeeming final chapter from the US version, so that the tale would end on a darker note, with Alex becoming his old, ultraviolent self again – an ending which the publisher insisted would be "more realistic" and appealing to a US audience. The film adaptation, directed by Stanley Kubrick, is based on the American edition of the book, and is considered to be "badly flawed" by Burgess. Kubrick called Chapter 21 "an extra chapter" and claimed that he had not read the original version until he had virtually finished the screenplay and that he had never given serious consideration to using it.[10] In Kubrick's opinion – as in the opinion of other readers, including the original American editor – the final chapter was unconvincing and inconsistent with the book.[8] Kubrick's stance was unusual when compared to the standard Hollywood practice of producing films with the familiar tropes of resolving moral messages and good triumphing over evil before the film's end.

Analysis[edit]

Background[edit]

A Clockwork Orange was written in Hove, then a senescent English seaside town.[12] Burgess had arrived back in Britain after his stint abroad to see that much had changed. A youth culture had developed, based around coffee bars, pop music and teenage gangs.[13] England was gripped by fears over juvenile delinquency.[12] Burgess stated that the novel's inspiration was his first wife Lynne's beating by a gang of drunk American servicemen stationed in England during World War II. She subsequently miscarried.[12][14] In its investigation of free will, the book's target is ostensibly the concept of behaviourism, pioneered by such figures as B. F. Skinner.[15] Burgess later stated that he wrote the book in three weeks.[12]

Title[edit]

Burgess has offered several clarifications about the meaning and origin of its title:

Reception[edit]

Initial response[edit]

The Sunday Telegraph review was positive, and described the book as "entertaining ... even profound".[28] Kingsley Amis in The Observer acclaimed the novel as "cheerful horror", writing "Mr Burgess has written a fine farrago of outrageousness, one which incidentally suggests a view of juvenile violence I can't remember having met before".[29] Malcolm Bradbury wrote "All of Mr Burgess's powers as a comic writer, which are considerable, have gone into the rich language of his inverted Utopia. If you can stomach the horrors, you'll enjoy the manner". Roald Dahl called it "a terrifying and marvellous book".[30] Many reviewers praised the inventiveness of the language, but expressed unease at the violent subject matter. The Spectator praised Burgess's "extraordinary technical feat" but was uncomfortable with "a certain arbitrariness about the plot which is slightly irritating". New Statesman acclaimed Burgess for addressing "acutely and savagely the tendencies of our time" but called the book "a great strain to read".[30] The Sunday Times review was negative, and described the book as "a very ordinary, brutal and psychologically shallow story".[31] The Times also reviewed the book negatively, describing it as "a somewhat clumsy experiment with science fiction [with] clumsy cliches about juvenile delinquency".[32] The violence was criticised as "unconvincing in detail".[32]