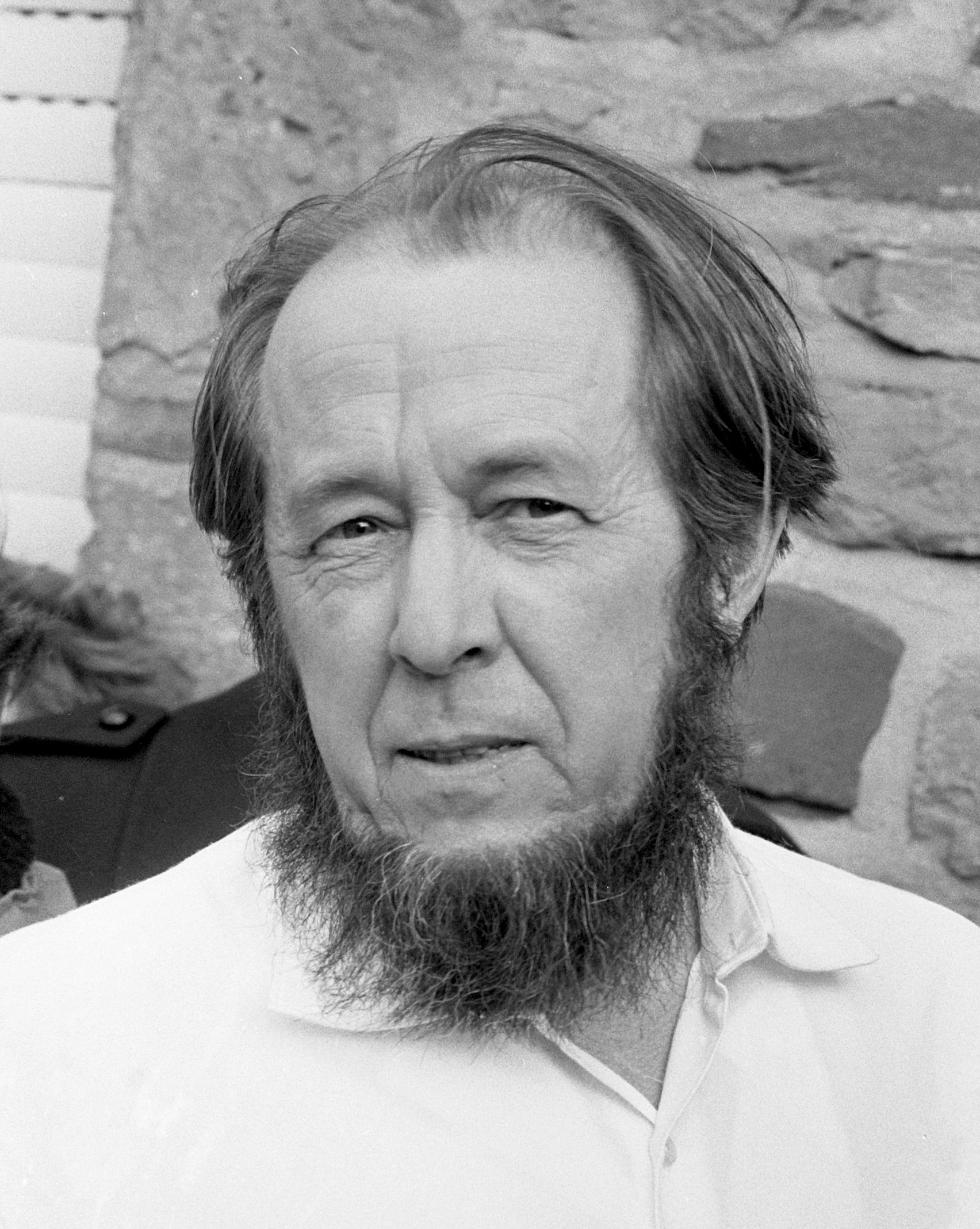

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn[a][b] (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008)[6][7] was a Russian writer and prominent Soviet dissident who helped to raise global awareness of political repression in the Soviet Union, especially the Gulag prison system.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

11 December 1918

Kislovodsk, Russian SFSR

3 August 2008 (aged 89)

Moscow, Russia

- Novelist

- essayist

- historian

- Nobel Prize in Literature (1970)

- Templeton Prize (1983)

- Lomonosov Gold Medal (1998)

- State Prize of the Russian Federation (2007)

- International Botev Prize (2008)

- Yermolai

- Ignat

- Stepan

Solzhenitsyn was born into a family that defied the Soviet anti-religious campaign in the 1920s and remained devout members of the Russian Orthodox Church. However, Solzhenitsyn initially lost his faith in Christianity, became an atheist, and embraced Marxism–Leninism. While serving as a captain in the Red Army during World War II, Solzhenitsyn was arrested by SMERSH and sentenced to eight years in the Gulag and then internal exile for criticizing Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in a private letter. As a result of his experience in prison and the camps, he gradually became a philosophically minded Eastern Orthodox Christian.

As a result of the Khrushchev Thaw, Solzhenitsyn was released and exonerated. He pursued writing novels about repression in the Soviet Union and his experiences. He published his first novel, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich in 1962, with approval from Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, which was an account of Stalinist repressions. Solzhenitsyn's last work to be published in the Soviet Union was Matryona's Place in 1963. Following the removal of Khrushchev from power, the Soviet authorities attempted to discourage Solzhenitsyn from continuing to write. He continued to work on further novels and their publication in other countries including Cancer Ward in 1966, In the First Circle in 1968, August 1914 in 1971, and The Gulag Archipelago in 1973, the publication of which outraged Soviet authorities. In 1974, Solzhenitsyn was stripped of his Soviet citizenship and flown to West Germany.[8] In 1976, he moved with his family to the United States, where he continued to write. In 1990, shortly before the dissolution of the Soviet Union, his citizenship was restored, and four years later he returned to Russia, where he remained until his death in 2008.

He was awarded the 1970 Nobel Prize in Literature "for the ethical force with which he has pursued the indispensable traditions of Russian literature",[9] and The Gulag Archipelago was a highly influential work that "amounted to a head-on challenge to the Soviet state", and sold tens of millions of copies.[10]

Biography[edit]

Early years[edit]

Solzhenitsyn was born in Kislovodsk (now in Stavropol Krai, Russia). His father, Isaakiy Semyonovich Solzhenitsyn, was of Russian descent and his mother, Taisiya Zakharovna (née Shcherbak), was of Ukrainian descent.[11] Taisiya's father had risen from humble beginnings to become a wealthy landowner, acquiring a large estate in the Kuban region in the northern foothills of the Caucasus[12] and during World War I, Taisiya had gone to Moscow to study. While there she met and married Isaakiy, a young officer in the Imperial Russian Army of Cossack origin and fellow native of the Caucasus region. The family background of his parents is vividly brought to life in the opening chapters of August 1914, and in the later Red Wheel novels.[13]

In 1918, Taisiya became pregnant with Aleksandr. On 15 June, shortly after her pregnancy was confirmed, Isaakiy was killed in a hunting accident. Aleksandr was raised by his widowed mother and his aunt in lowly circumstances. His earliest years coincided with the Russian Civil War. By 1930 the family property had been turned into a collective farm. Later, Solzhenitsyn recalled that his mother had fought for survival and that they had to keep his father's background in the old Imperial Army a secret. His educated mother encouraged his literary and scientific learnings and raised him in the Russian Orthodox faith;[14][15] she died in 1944 having never remarried.[16]

As early as 1936, Solzhenitsyn began developing the characters and concepts for planned epic work on World War I and the Russian Revolution. This eventually led to the novel August 1914; some of the chapters he wrote then still survive. Solzhenitsyn studied mathematics and physics at Rostov State University. At the same time, he took correspondence courses from the Moscow Institute of Philosophy, Literature and History, which by this time were heavily ideological in scope. As he himself makes clear, he did not question the state ideology or the superiority of the Soviet Union until he was sentenced to time in the camps.[17]

World War II[edit]

During the war, Solzhenitsyn served as the commander of a sound-ranging battery in the Red Army,[18] was involved in major action at the front, and was twice decorated. He was awarded the Order of the Red Star on 8 July 1944 for sound-ranging two German artillery batteries and adjusting counterbattery fire onto them, resulting in their destruction.[19]

A series of writings published late in his life, including the early uncompleted novel Love the Revolution!, chronicle his wartime experience and growing doubts about the moral foundations of the Soviet regime.[20]

While serving as an artillery officer in East Prussia, Solzhenitsyn witnessed war crimes against local German civilians by Soviet military personnel. Of the atrocities, Solzhenitsyn wrote: "You know very well that we've come to Germany to take our revenge" for Nazi atrocities committed in the Soviet Union.[21] The noncombatants and the elderly were robbed of their meager possessions and women and girls were gang-raped. A few years later, in the forced labor camp, he memorized a poem titled "Prussian Nights" about a woman raped to death in East Prussia. In this poem, which describes the gang-rape of a Polish woman whom the Red Army soldiers mistakenly thought to be a German,[22] the first-person narrator comments on the events with sarcasm and refers to the responsibility of official Soviet writers like Ilya Ehrenburg.

In The Gulag Archipelago, Solzhenitsyn wrote, "There is nothing that so assists the awakening of omniscience within us as insistent thoughts about one's own transgressions, errors, mistakes. After the difficult cycles of such ponderings over many years, whenever I mentioned the heartlessness of our highest-ranking bureaucrats, the cruelty of our executioners, I remember myself in my Captain's shoulder boards and the forward march of my battery through East Prussia, enshrouded in fire, and I say: 'So were we any better?'"[23]

Imprisonment[edit]

In February 1945, while serving in East Prussia, Solzhenitsyn was arrested by SMERSH for writing derogatory comments in private letters to a friend, Nikolai Vitkevich,[24] about the conduct of the war by Joseph Stalin, whom he called "Khozyain" ("the boss"), and "Balabos" (Yiddish rendering of Hebrew baal ha-bayit for "master of the house").[25] He also had talks with the same friend about the need for a new organization to replace the Soviet regime.[26]

Solzhenitsyn was accused of anti-Soviet propaganda under Article 58, paragraph 10 of the Soviet criminal code, and of "founding a hostile organization" under paragraph 11.[27][28] Solzhenitsyn was taken to the Lubyanka prison in Moscow, where he was interrogated. On 9 May 1945, it was announced that Germany had surrendered and all of Moscow broke out in celebrations with fireworks and searchlights illuminating the sky to celebrate the victory in the Great Patriotic War. From his cell in the Lubyanka, Solzhenitsyn remembered: "Above the muzzle of our window, and from all the other cells of the Lubyanka, and from all the windows of the Moscow prisons, we too, former prisoners of war and former front-line soldiers, watched the Moscow heavens, patterned with fireworks and crisscrossed with beams of searchlights. There was no rejoicing in our cells and no hugs and no kisses for us. That victory was not ours."[29] On 7 July 1945, he was sentenced in his absence by Special Council of the NKVD to an eight-year term in a labour camp. This was the usual sentence for most crimes under Article 58 at the time.[30]

The first part of Solzhenitsyn's sentence was served in several work camps; the "middle phase", as he later referred to it, was spent in a sharashka (a special scientific research facility run by Ministry of State Security), where he met Lev Kopelev, upon whom he based the character of Lev Rubin in his book The First Circle, published in a self-censored or "distorted" version in the West in 1968 (an English translation of the full version was eventually published by Harper Perennial in October 2009).[31] In 1950, Solzhenitsyn was sent to a "Special Camp" for political prisoners. During his imprisonment at the camp in the town of Ekibastuz in Kazakhstan, he worked as a miner, bricklayer, and foundry foreman. His experiences at Ekibastuz formed the basis for the book One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. One of his fellow political prisoners, Ion Moraru, remembers that Solzhenitsyn spent some of his time at Ekibastuz writing.[32] While there, Solzhenitsyn had a tumor removed. His cancer was not diagnosed at the time.

In March 1953, after his sentence ended, Solzhenitsyn was sent to internal exile for life at Birlik,[33] a village in Baidibek District of South Kazakhstan.[34] His undiagnosed cancer spread until, by the end of the year, he was close to death. In 1954, Solzhenitsyn was permitted to be treated in a hospital in Tashkent, where his tumor went into remission. His experiences there became the basis of his novel Cancer Ward and also found an echo in the short story "The Right Hand."

It was during this decade of imprisonment and exile that Solzhenitsyn developed the philosophical and religious positions of his later life, gradually becoming a philosophically minded Eastern Orthodox Christian as a result of his experience in prison and the camps.[35][36][37] He repented for some of his actions as a Red Army captain, and in prison compared himself to the perpetrators of the Gulag. His transformation is described at some length in the fourth part of The Gulag Archipelago ("The Soul and Barbed Wire"). The narrative poem The Trail (written without benefit of pen or paper in prison and camps between 1947 and 1952) and the 28 poems composed in prison, forced-labour camp, and exile also provide crucial material for understanding Solzhenitsyn's intellectual and spiritual odyssey during this period. These "early" works, largely unknown in the West, were published for the first time in Russian in 1999 and excerpted in English in 2006.[38][39]

Marriages and children[edit]

On 7 April 1940, while at the university, Solzhenitsyn married Natalia Alekseevna Reshetovskaya.[40] They had just over a year of married life before he went into the army, then to the Gulag. They divorced in 1952, a year before his release because the wives of Gulag prisoners faced the loss of work or residence permits. After the end of his internal exile, they remarried in 1957,[41] divorcing a second time in 1972. Reshetovskaya wrote negatively of Solzhenitsyn in her memoirs, accusing him of having affairs, and said of the relationship that "[Solzhenitsyn]'s despotism ... would crush my independence and would not permit my personality to develop."[42] In her 1974 memoir, Sanya: My Life with Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, she wrote that she was "perplexed" that the West had accepted The Gulag Archipelago as "the solemn, ultimate truth", saying its significance had been "overestimated and wrongly appraised". Pointing out that the book's subtitle is "An Experiment in Literary Investigation", she said that her husband did not regard the work as "historical research, or scientific research". She contended that it was, rather, a collection of "camp folklore", containing "raw material" which her husband was planning to use in his future productions.

In 1973, Solzhenitsyn married his second wife, Natalia Dmitrievna Svetlova, a mathematician who had a son, Dmitri Turin, from a brief prior marriage.[43] He and Svetlova (born 1939) had three sons: Yermolai (1970), Ignat (1972), and Stepan (1973).[44] Dmitri Turin died on 18 March 1994, aged 32, at his home in New York City.[45]

After prison[edit]

After Khrushchev's Secret Speech in 1956, Solzhenitsyn was freed from exile and exonerated. Following his return from exile, Solzhenitsyn was, while teaching at a secondary school during the day, spending his nights secretly engaged in writing. In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech he wrote that "during all the years until 1961, not only was I convinced I should never see a single line of mine in print in my lifetime, but, also, I scarcely dared allow any of my close acquaintances to read anything I had written because I feared this would become known."[46]

In 1960, aged 42, Solzhenitsyn approached Aleksandr Tvardovsky, a poet and the chief editor of the Novy Mir magazine, with the manuscript of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. It was published in edited form in 1962, with the explicit approval of Nikita Khrushchev, who defended it at the presidium of the Politburo hearing on whether to allow its publication, and added: "There's a Stalinist in each of you; there's even a Stalinist in me. We must root out this evil."[47] The book quickly sold out and became an instant hit.[48] In the 1960s, while Solzhenitsyn was publicly known to be writing Cancer Ward, he was simultaneously writing The Gulag Archipelago. During Khrushchev's tenure, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich was studied in schools in the Soviet Union, as were three more short works of Solzhenitsyn's, including his short story "Matryona's Home", published in 1963. These would be the last of his works published in the Soviet Union until 1990.

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich brought the Soviet system of prison labour to the attention of the West. It caused as much of a sensation in the Soviet Union as it did in the West—not only by its striking realism and candour, but also because it was the first major piece of Soviet literature since the 1920s on a politically charged theme, written by a non-party member, indeed a man who had been to Siberia for "libelous speech" about the leaders, and yet its publication had been officially permitted. In this sense, the publication of Solzhenitsyn's story was an almost unheard of instance of free, unrestrained discussion of politics through literature. However, after Khrushchev had been ousted from power in 1964, the time for such raw, exposing works came to an end.[48]