Ancient Mesopotamian religion

Mesopotamian religion refers to the religious beliefs (concerning the gods, creation and the cosmos, the origin of man, and so forth) and practices of the civilizations of ancient Mesopotamia, particularly Sumer, Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia between circa 6000 BC[1] and 400 AD. The religious development of Mesopotamia and Mesopotamian culture in general, especially in the south, were not particularly influenced by the movements of the various peoples into and throughout the area. Rather, Mesopotamian religion was a consistent and coherent tradition, which adapted to the internal needs of its adherents over millennia of development.[2]

The earliest undercurrents of Mesopotamian religious thought are believed to have developed in Mesopotamia in the 6th millennium BC, coinciding with when the region began to be permanently settled.[1] The earliest evidence of Mesopotamian religion dates to the mid-4th millennium BC, coincides with the invention of writing, and involved the worship of forces of nature as providers of sustenance. In the 3rd millennium BC, objects of worship were personified and became an expansive cast of divinities with particular functions. The last stages of Mesopotamian polytheism, which developed in the 2nd and 1st millennia BC, introduced greater emphasis on personal religion and structured the gods into a monarchical hierarchy, with the national god being the head of the pantheon.[2] Mesopotamian religion finally declined with the spread of Iranian religions during the Achaemenid Empire and with the Christianization of Mesopotamia.

Afterlife[edit]

Mesopotamians believed in an afterlife that took place in a region below the surface of the earth inhabited by living humans. This was the ancient Mesopotamian underworld, known by many names including Arallû, Ganzer or Irkallu ("Great Below"). It was believed everyone went to this region after death, irrespective of social status or the actions performed during their lifetime.[56] Unlike Christian hell, the Mesopotamians considered the underworld neither a punishment nor a reward.[57] Nevertheless, the condition of the dead was hardly considered the same as the life previously enjoyed on earth: they were considered merely weak and powerless ghosts. The myth of Ishtar's descent into the underworld relates that "dust is their food and clay their nourishment, they see no light, where they dwell in darkness." Stories such as the Adapa myth resignedly relate that, due to a blunder, all men must die and that true everlasting life is the sole property of the gods.[18]

Eschatology[edit]

There are no known Mesopotamian tales about the end of the world, although it has been speculated that they believed that this would eventually occur. This is largely because Berossus wrote that the Mesopotamians believed the world to last "twelve times twelve sars" in his Babyloniaca; with a sar being 3,600 years, this would indicate that at least some of the Mesopotamians believed that the Earth would only last 518,400 years. Berossus does not report what was thought to follow this event, however.[58]

Historiography[edit]

Reconstruction[edit]

As with most dead religions, many aspects of the common practices and intricacies of the doctrine have been lost and forgotten over time. However, much of the information and knowledge has survived, and great work has been done by historians and scientists, with the help of religious scholars and translators, to re-construct a working knowledge of the religious history, customs, and the role these beliefs played in everyday life in Sumer, Akkad, Assyria, Babylonia, Ebla and Chaldea during this time. Mesopotamian religion is thought to have been an influence on subsequent religions throughout the world, including Canaanite/Israelite, Aramean, and ancient Greek.

Mesopotamian religion was polytheistic, worshipping over 2,100 different deities, many of which were associated with a specific state within Mesopotamia, such as Sumer, Akkad, Assyria or Babylonia, or a specific Mesopotamian city.[16]

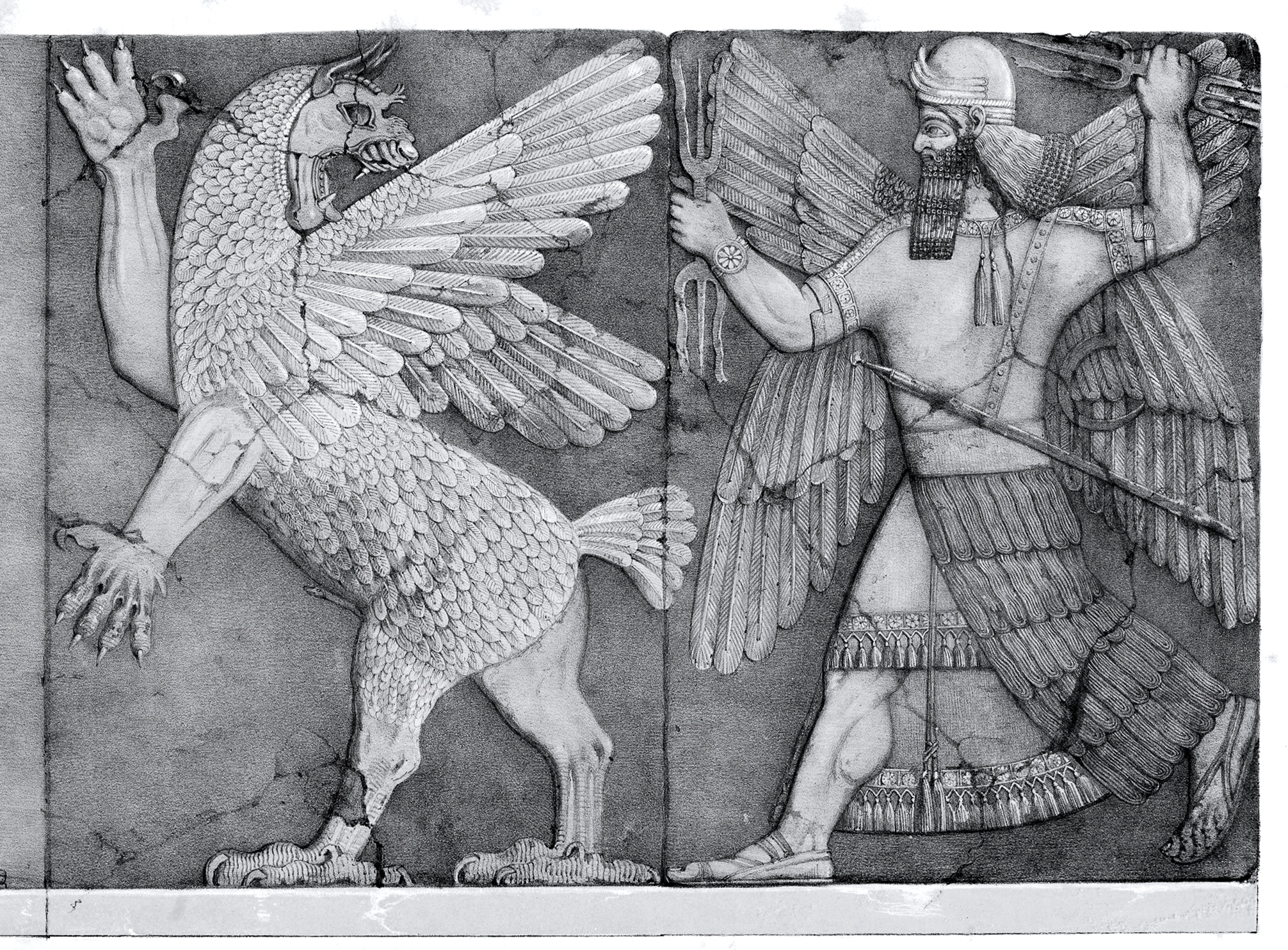

Mesopotamian religion has historically the oldest body of recorded literature of any religious tradition. What is known about Mesopotamian religion comes from archaeological evidence uncovered in the region, particularly numerous literary sources, which are usually written in Sumerian, Akkadian (Assyro-Babylonian) or Aramaic using cuneiform script on clay tablets and which describe both mythology and cultic practices. Other artifacts can also be useful when reconstructing Mesopotamian religion. As is common with most ancient civilizations, the objects made of the most durable and precious materials, and thus more likely to survive, were associated with religious beliefs and practices. This has prompted one scholar to make the claim that the Mesopotamian's "entire existence was infused by their religiosity, just about everything they have passed on to us can be used as a source of knowledge about their religion."[59]

Challenges[edit]

The modern study of Mesopotamia (Assyriology) is still a fairly young science, beginning only in the middle of the Nineteenth century,[60] and the study of Mesopotamian religion can be a complex and difficult subject because, by nature, their religion was governed only by usage, not by any official decision,[61] and by nature it was neither dogmatic nor systematic. Deities, characters, and their actions within myths changed in character and importance over time, and occasionally depicted different, sometimes even contrasting images or concepts. This is further complicated by the fact that scholars are not entirely certain what role religious texts played in the Mesopotamian world.[62]

A number of scholars once argued that defining a single Mesopotamian religion was not possible, and as such, a systematic exposition of Mesopotamian religion should not be produced.[63] Other have rebutted that this is a mistaken approach, insofar as it would fracture the study of religion among social divisions (such as private religion, religion of the educated), individual cities and provinces (Ebla, Mari, Assyria), and time periods (Seleucid, Achaemenid, etc), and that this fracture would be counterproductive as the succession of ancient near eastern states did not impact the presence of a broadly shared religious system across them.[64]

Influence[edit]

General[edit]

While Mesopotamian religion had almost completely died out by approximately 400–500 CE after its indigenous adherents had largely become Assyrian Christians, it has still had an influence on the modern world, predominantly because many biblical stories that are today found in Judaism, Christianity, Islam and Mandaeism were possibly based upon earlier Mesopotamian myths, in particular that of the creation myth, the Garden of Eden, the flood myth, the Tower of Babel, figures such as Nimrod and Lilith and the Book of Esther. It has also inspired various contemporary neo-pagan groups.