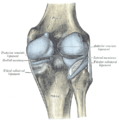

Anterior cruciate ligament

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of a pair of cruciate ligaments (the other being the posterior cruciate ligament) in the human knee. The two ligaments are also called "cruciform" ligaments, as they are arranged in a crossed formation. In the quadruped stifle joint (analogous to the knee), based on its anatomical position, it is also referred to as the cranial cruciate ligament.[1] The term cruciate translates to cross. This name is fitting because the ACL crosses the posterior cruciate ligament to form an "X". It is composed of strong, fibrous material and assists in controlling excessive motion. This is done by limiting mobility of the joint. The anterior cruciate ligament is one of the four main ligaments of the knee, providing 85% of the restraining force to anterior tibial displacement at 30 and 90° of knee flexion.[2] The ACL is the most injured ligament of the four located in the knee.

This article is about the ligament. For other uses, see ACL (disambiguation).Anterior cruciate ligament

Structure[edit]

The ACL originates from deep within the notch of the distal femur. Its proximal fibers fan out along the medial wall of the lateral femoral condyle.[3] The two bundles of the ACL are the anteromedial and the posterolateral, named according to where the bundles insert into the tibial plateau.[4][5] The tibial plateau is a critical weight-bearing region on the upper extremity of the tibia. The ACL attaches in front of the intercondyloid eminence of the tibia, where it blends with the anterior horn of the medial meniscus.

Purpose[edit]

The purpose of the ACL is to resist the motions of anterior tibial translation and internal tibial rotation; this is important to have rotational stability.[6] This function prevents anterior tibial subluxation of the lateral and medial tibiofemoral joints, which is important for the pivot-shift phenomenon.[6] The ACL has mechanoreceptors that detect changes in direction of movement, position of the knee joint, and changes in acceleration, speed, and tension.[7] A key factor in instability after ACL injuries is having altered neuromuscular function secondary to diminished somatosensory information.[7] For athletes who participate in sports involving cutting, jumping, and rapid deceleration, the knee must be stable in terminal extension, which is the screw-home mechanism.[7]