Battle of Vittorio Veneto

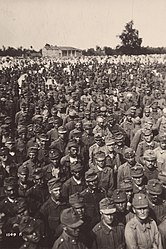

The Battle of Vittorio Veneto was fought from 24 October to 3 November 1918 (with an armistice taking effect 24 hours later) near Vittorio Veneto on the Italian Front during World War I. After having thoroughly defeated Austro-Hungarian troops during the defensive Battle of the Piave River, the Italian army launched a great counter-offensive: the Italian victory[1][2][9] marked the end of the war on the Italian Front, secured the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and contributed to the end of the First World War just one week later.[4] On 1 November, the new Hungarian government of Count Mihály Károlyi decided to recall all of the troops, who were conscripted from the territory of Kingdom of Hungary, which was a major blow for the Habsburgs' armies.[10] The battle led to the capture of over 5,000 artillery pieces and over 350,000 Austro-Hungarian troops, including 120,000 Germans, 83,000 Czechs and Slovaks, 60,000 South Slavs, 40,000 Poles, several tens of thousands of Romanians and Ukrainians, and 7,000 Austro-Hungarian loyalist Italians and Friulians.[11][12]

Name[edit]

When the battle was fought in November 1918, the nearby city was called simply Vittorio,[13] named in 1866 for Vittorio Emanuele II, monarch from 1861 of the newly created Kingdom of Italy. The engagement, the last major battle in the war (1915–1918) between Italy and Austria-Hungary, was generally referred to as the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, i.e. 'Vittorio in the Veneto region'. The city's name was officially changed to Vittorio Veneto in July 1923.[14]

The Allies:[21][22](Armando Diaz)

Austria-Hungary[25]

Prelude[edit]

As night fell on 23 October, leading elements of Lord Cavan's Tenth Army were to force a crossing at a point where there were a number of islands. Cavan had decided to seize the largest of these – the Grave di Papadopoli – in preparation for the full-scale assault on the far bank. The plan was for two battalions from the 22nd Brigade of the British 7th Division to occupy the northern half of Papadopoli, while the Italian 11th Corps took the southern half.[26] The British troops detailed for the night attack were the 2/1 Honourable Artillery Company (an infantry battalion despite the title) and the 1/ Royal Welch Fusiliers. These troops were helpless to negotiate such a torrent as the Piave and relied upon boats propelled by the 18th Pontieri under the command of Captain Odini of the Italian engineers. On the misty night of the 23rd, the Italians rowed the British forces across with a calm assurance and skill which amazed many of those who were more frightened of drowning than of fighting the Austrians. For the sake of silence, the HAC used only their bayonets until the alarm was raised, and soon seized their half of the island. The Italian assault on the south of Papadopoli was driven off by heavy machine-gun fire. Nevertheless, the Austrians surrendered the island by the end of the night.[27]

Assessment[edit]

German chief-of-staff Erich Ludendorff, a prominent World War I figure, stressed the importance of the battle, claiming that its outcome prompted the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, "dragging Germany in its fall".[4] In his memories Ludendorff wrote: "The Austro-Hungarian Army had completely dissolved as a result of the fighting in Upper Italy between the 24th October and the 4th November. Hostile forces were moving on Innsbruck. G.H.Q. took comprehensive measures for the protection of the southern frontier of Bavaria. In the Balkan theatre we held the Danube. We stood alone in the world. At the beginning of November the Revolution, the work of the Independent Socialists, broke out, starting in the navy."[41] German historian Ernst Nolte contended that Vittorio Veneto was "an encounter which had merely given the coup de grace to the abandoned army of an already crumbling state."[42]