Biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the distribution of species and ecosystems in geographic space and through geological time. Organisms and biological communities often vary in a regular fashion along geographic gradients of latitude, elevation, isolation and habitat area.[1] Phytogeography is the branch of biogeography that studies the distribution of plants. Zoogeography is the branch that studies distribution of animals. Mycogeography is the branch that studies distribution of fungi, such as mushrooms.

Knowledge of spatial variation in the numbers and types of organisms is as vital to us today as it was to our early human ancestors, as we adapt to heterogeneous but geographically predictable environments. Biogeography is an integrative field of inquiry that unites concepts and information from ecology, evolutionary biology, taxonomy, geology, physical geography, palaeontology, and climatology.[2][3]

Modern biogeographic research combines information and ideas from many fields, from the physiological and ecological constraints on organismal dispersal to geological and climatological phenomena operating at global spatial scales and evolutionary time frames.

The short-term interactions within a habitat and species of organisms describe the ecological application of biogeography. Historical biogeography describes the long-term, evolutionary periods of time for broader classifications of organisms.[4] Early scientists, beginning with Carl Linnaeus, contributed to the development of biogeography as a science.

The scientific theory of biogeography grows out of the work of Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859),[5] Francisco Jose de Caldas (1768–1816),[6] Hewett Cottrell Watson (1804–1881),[7] Alphonse de Candolle (1806–1893),[8] Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913),[9] Philip Lutley Sclater (1829–1913) and other biologists and explorers.[10]

Introduction[edit]

The patterns of species distribution across geographical areas can usually be explained through a combination of historical factors such as: speciation, extinction, continental drift, and glaciation. Through observing the geographic distribution of species, we can see associated variations in sea level, river routes, habitat, and river capture. Additionally, this science considers the geographic constraints of landmass areas and isolation, as well as the available ecosystem energy supplies.

Over periods of ecological changes, biogeography includes the study of plant and animal species in: their past and/or present living refugium habitat; their interim living sites; and/or their survival locales.[11] As writer David Quammen put it, "...biogeography does more than ask Which species? and Where. It also asks Why? and, what is sometimes more crucial, Why not?."[12]

Modern biogeography often employs the use of Geographic Information Systems (GIS), to understand the factors affecting organism distribution, and to predict future trends in organism distribution.[13]

Often mathematical models and GIS are employed to solve ecological problems that have a spatial aspect to them.[14]

Biogeography is most keenly observed on the world's islands. These habitats are often much more manageable areas of study because they are more condensed than larger ecosystems on the mainland.[15] Islands are also ideal locations because they allow scientists to look at habitats that new invasive species have only recently colonized and can observe how they disperse throughout the island and change it. They can then apply their understanding to similar but more complex mainland habitats. Islands are very diverse in their biomes, ranging from the tropical to arctic climates. This diversity in habitat allows for a wide range of species study in different parts of the world.

One scientist who recognized the importance of these geographic locations was Charles Darwin, who remarked in his journal "The Zoology of Archipelagoes will be well worth examination".[15] Two chapters in On the Origin of Species were devoted to geographical distribution.

History[edit]

18th century[edit]

The first discoveries that contributed to the development of biogeography as a science began in the mid-18th century, as Europeans explored the world and described the biodiversity of life. During the 18th century most views on the world were shaped around religion and for many natural theologists, the bible. Carl Linnaeus, in the mid-18th century, improved our classifications of organisms through the exploration of undiscovered territories by his students and disciples. When he noticed that species were not as perpetual as he believed, he developed the Mountain Explanation to explain the distribution of biodiversity; when Noah's ark landed on Mount Ararat and the waters receded, the animals dispersed throughout different elevations on the mountain. This showed different species in different climates proving species were not constant.[4] Linnaeus' findings set a basis for ecological biogeography. Through his strong beliefs in Christianity, he was inspired to classify the living world, which then gave way to additional accounts of secular views on geographical distribution.[10] He argued that the structure of an animal was very closely related to its physical surroundings. This was important to a George Louis Buffon's rival theory of distribution.[10]

Closely after Linnaeus, Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon observed shifts in climate and how species spread across the globe as a result. He was the first to see different groups of organisms in different regions of the world. Buffon saw similarities between some regions which led him to believe that at one point continents were connected and then water separated them and caused differences in species. His hypotheses were described in his work, the 36 volume Histoire Naturelle, générale et particulière, in which he argued that varying geographical regions would have different forms of life. This was inspired by his observations comparing the Old and New World, as he determined distinct variations of species from the two regions. Buffon believed there was a single species creation event, and that different regions of the world were homes for varying species, which is an alternate view than that of Linnaeus. Buffon's law eventually became a principle of biogeography by explaining how similar environments were habitats for comparable types of organisms.[10] Buffon also studied fossils which led him to believe that the Earth was over tens of thousands of years old, and that humans had not lived there long in comparison to the age of the Earth.[4]

19th century[edit]

Following the period of exploration came the Age of Enlightenment in Europe, which attempted to explain the patterns of biodiversity observed by Buffon and Linnaeus. At the birth of the 19th century, Alexander von Humboldt, known as the "founder of plant geography",[4] developed the concept of physique generale to demonstrate the unity of science and how species fit together. As one of the first to contribute empirical data to the science of biogeography through his travel as an explorer, he observed differences in climate and vegetation. The Earth was divided into regions which he defined as tropical, temperate, and arctic and within these regions there were similar forms of vegetation.[4] This ultimately enabled him to create the isotherm, which allowed scientists to see patterns of life within different climates.[4] He contributed his observations to findings of botanical geography by previous scientists, and sketched this description of both the biotic and abiotic features of the Earth in his book, Cosmos.[10]

Augustin de Candolle contributed to the field of biogeography as he observed species competition and the several differences that influenced the discovery of the diversity of life. He was a Swiss botanist and created the first Laws of Botanical Nomenclature in his work, Prodromus.[16] He discussed plant distribution and his theories eventually had a great impact on Charles Darwin, who was inspired to consider species adaptations and evolution after learning about botanical geography. De Candolle was the first to describe the differences between the small-scale and large-scale distribution patterns of organisms around the globe.[10]

Several additional scientists contributed new theories to further develop the concept of biogeography. Charles Lyell developed the Theory of Uniformitarianism after studying fossils. This theory explained how the world was not created by one sole catastrophic event, but instead from numerous creation events and locations.[17] Uniformitarianism also introduced the idea that the Earth was actually significantly older than was previously accepted. Using this knowledge, Lyell concluded that it was possible for species to go extinct.[18] Since he noted that Earth's climate changes, he realized that species distribution must also change accordingly. Lyell argued that climate changes complemented vegetation changes, thus connecting the environmental surroundings to varying species. This largely influenced Charles Darwin in his development of the theory of evolution.[10]

Charles Darwin was a natural theologist who studied around the world, and most importantly in the Galapagos Islands. Darwin introduced the idea of natural selection, as he theorized against previously accepted ideas that species were static or unchanging. His contributions to biogeography and the theory of evolution were different from those of other explorers of his time, because he developed a mechanism to describe the ways that species changed. His influential ideas include the development of theories regarding the struggle for existence and natural selection. Darwin's theories started a biological segment to biogeography and empirical studies, which enabled future scientists to develop ideas about the geographical distribution of organisms around the globe.[10]

Alfred Russel Wallace studied the distribution of flora and fauna in the Amazon Basin and the Malay Archipelago in the mid-19th century. His research was essential to the further development of biogeography, and he was later nicknamed the "father of Biogeography". Wallace conducted fieldwork researching the habits, breeding and migration tendencies, and feeding behavior of thousands of species. He studied butterfly and bird distributions in comparison to the presence or absence of geographical barriers. His observations led him to conclude that the number of organisms present in a community was dependent on the amount of food resources in the particular habitat.[10] Wallace believed species were dynamic by responding to biotic and abiotic factors. He and Philip Sclater saw biogeography as a source of support for the theory of evolution as they used Darwin's conclusion to explain how biogeography was similar to a record of species inheritance.[10] Key findings, such as the sharp difference in fauna either side of the Wallace Line, and the sharp difference that existed between North and South America prior to their relatively recent faunal interchange, can only be understood in this light. Otherwise, the field of biogeography would be seen as a purely descriptive one.[4]

Biogeographic regionalisations[edit]

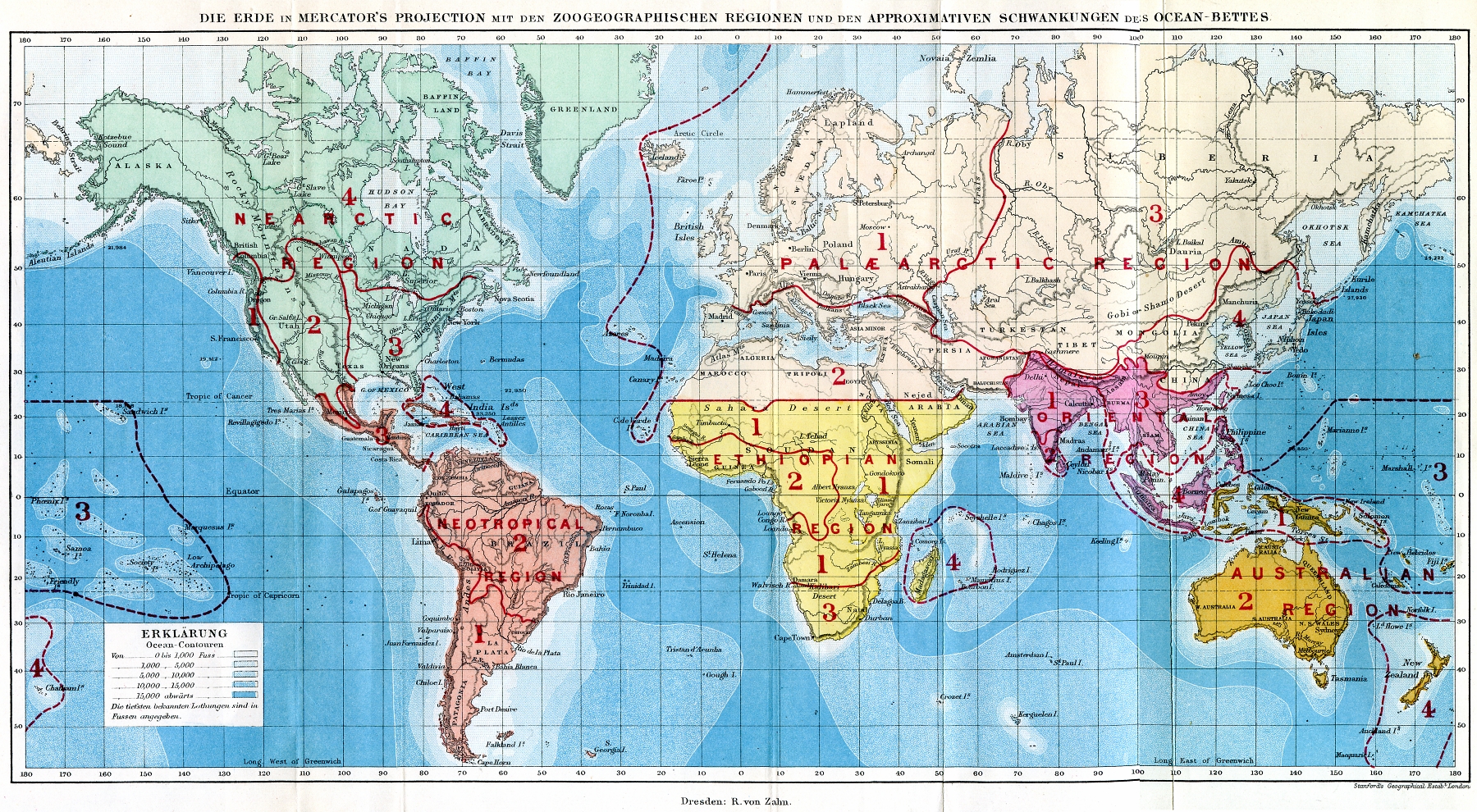

There are many types of biogeographic units used in biogeographic regionalisation schemes,[38][39][40] as there are many criteria (species composition, physiognomy, ecological aspects) and hierarchization schemes: biogeographic realms (ecozones), bioregions (sensu stricto), ecoregions, zoogeographical regions, floristic regions, vegetation types, biomes, etc.

The terms biogeographic unit,[41] biogeographic area[42] can be used for these categories, regardless of rank.

In 2008, an International Code of Area Nomenclature was proposed for biogeography.[43][44][45] It achieved limited success; some studies commented favorably on it, but others were much more critical,[46] and it "has not yet gained a significant following".[47] Similarly, a set of rules for paleobiogeography[48] has achieved limited success.[47][49] In 2000, Westermann suggested that the difficulties in getting formal nomenclatural rules established in this field might be related to "the curious fact that neither paleo- nor neobiogeographers are organized in any formal groupings or societies, nationally (so far as I know) or internationally — an exception among active disciplines."[50]