Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis

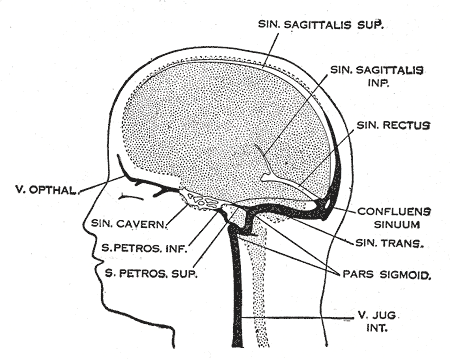

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST), cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis or cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT), is the presence of a blood clot in the dural venous sinuses (which drain blood from the brain), the cerebral veins, or both. Symptoms may include severe headache, visual symptoms, any of the symptoms of stroke such as weakness of the face and limbs on one side of the body, and seizures, which occur in around 40% of patients.[2]

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis

Cerebral venous and sinus thrombosis, (superior) sagittal sinus thrombosis, dural sinus thrombosis, intracranial venous thrombosis, cerebral thrombophlebitis

The diagnosis is usually by computed tomography (CT scan) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to demonstrate obstruction of the venous sinuses.[3] After confirmation of the diagnosis, investigations may be performed to determine the underlying cause, especially if one is not readily apparent.

Treatment is typically with anticoagulants (medications that suppress blood clotting) such as low molecular weight heparin.[1] Rarely, thrombolysis (enzymatic destruction of the blood clot) or mechanical thrombectomy is used, although evidence for this therapy is limited.[4] The disease may be complicated by raised intracranial pressure, which may warrant surgical intervention such as the placement of a shunt.[3]

Signs and symptoms[edit]

Nine in ten people with cerebral venous thrombosis have a headache; this tends to worsen over the period of several days, but may also develop suddenly (thunderclap headache).[3] The headache may be the only symptom.[5] Many have symptoms of stroke: inability to move one or more limbs, weakness on one side of the face or difficulty speaking. The neurologic deficits related to central venous thromboses does not necessarily affect one side of the body or one arterial or brain territory as is more common "arterial" strokes.[3][6] Bilateral 6th cranial nerve palsies may occur, causing abnormalities related to eye movement, but this is rare.[6]

40% of people have seizures, although it is more common in women who develop sinus thrombosis peripartum (in the period before and after giving birth).[7] These are mostly seizures affecting only one part of the body and unilateral (occurring on one side), but occasionally the seizures are generalised and rarely they lead to status epilepticus (persistent or recurrent seizure activity for a long period of time).[3]

In the elderly, many of the aforementioned symptoms may not occur. Common symptoms in the elderly with this condition are otherwise unexplained changes in mental status and a depressed level of consciousness.[8]

The pressure around the brain may rise, causing papilledema (swelling of the optic disc) which may be experienced as visual obscurations. In severely raised intracranial pressure, the level of consciousness is decreased, the blood pressure rises, the heart rate falls and there is abnormal posturing.[3]

Focal neurologic deficits may occur hours to days after the headache in 50% of cases, this may present as hemiparesis (unilateral weakness) if due to infarction of the frontal or parietal lobe which are drained by the vein of Trolard. Focal deficits may also present as aphasia or confusion if the vein of Labbe (responsible for draining the temporal lobe) is affected.[6]

Disorders that cause, or increase the risk for systemic venous thrombosis are associated with central venous thromboses.[6][9] In children, head and neck infections and acute systemic illnesses are the primary cause of central venous thrombosis.[6] Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis is more common in particular situations. 85% of people have at least one of these risk factors:[3]

Treatment[edit]

Various studies have investigated the use of anticoagulation to suppress blood clot formation in cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Before these trials had been conducted, there had been a concern that small areas of hemorrhage in the brain would bleed further as a result of treatment; the studies showed that this concern was unfounded.[16] Clinical practice guidelines now recommend heparin or low molecular weight heparin in the initial treatment, followed by warfarin, provided there are no other bleeding risks that would make these treatments unsuitable.[7][17][18] Some experts discourage the use of anticoagulation if there is extensive hemorrhage; in that case, they recommend repeating the imaging after 7–10 days. If the hemorrhage has decreased in size, anticoagulants are started, while no anticoagulants are given if there is no reduction.[19]

The duration of warfarin treatment depends on the circumstances and underlying causes of the condition. If the thrombosis developed under temporary circumstances (e.g. pregnancy), three months are regarded as sufficient. If the condition was unprovoked but there are no clear causes or a "mild" form of thrombophilia, 6 to 12 months is advised. If there is a severe underlying thrombosis disorder, warfarin treatment may need to continue indefinitely.[7]

Heparin and platelet transfusions should not be used as a treatment for any form of cerebral venous thrombosis caused by immune thrombotic thrombocytopenias including Heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), auto-immune heparin induced thrombocytopenia (aHIT) or vaccine induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT) due to unpredictable effects of heparin on anti-platelet factor-4 antibodies (PF-4). In cases of VITT, intravenous immune globulins (IVIG) are recommended as they block the anti-PF4 antibody interaction with platelets and a non-heparin anticoagulant. In refractory cases, plasma exchange may be used.[6]

Thrombolysis (removal of the blood clot with "clot buster" medication) has been described, either systemically by injection into a vein or directly into the clot during angiography. The 2006 European Federation of Neurological Societies guideline recommends that thrombolysis is only used in people who deteriorate despite adequate treatment, and other causes of deterioration have been eliminated. It is unclear which drug and which mode of administration is the most effective. Bleeding into the brain and in other sites of the body is a major concern in the use of thrombolysis.[7] American guidelines make no recommendation with regards to thrombolysis, stating that more research is needed.[18]

In those where a venous infarct or hemorrhage causes significant compression of surrounding brain structures, decompressive craniectomy is sometimes required.[20] Raised intracranial pressure, if severe or threatening vision, may require therapeutic lumbar puncture (removal of excessive cerebrospinal fluid), or neurosurgical treatment (optic nerve sheath fenestration or shunting).[3] Venous stenting is emerging as a minimally invasive, safer alternative to shunting.[21] In certain situations, anticonvulsants may be used to try to prevent seizures.[7] These situations include focal neurological problems (e.g. inability to move a limb) and focal changes of the brain tissue on CT or MRI scan.[7] Evidence to support or refute the use of antiepileptic drugs as a preventive measure, however, is lacking.[22]

Prognosis[edit]

In 2004 the first adequately large scale study on the natural history and long-term prognosis of this condition was reported; this showed that at 16 months follow-up 57.1% of people had full recovery, 29.5%/2.9%/2.2% had respectively minor/moderate/severe symptoms or impairments, and 8.3% had died. Severe impairment or death were more likely in those aged over 37 years, male, affected by coma, mental status disorder, intracerebral hemorrhage, thrombosis of the deep cerebral venous system, central nervous system infection and cancer.[23] A subsequent systematic review of nineteen studies in 2006 showed that mortality is about 5.6% during hospitalisation and 9.4% in total, while of the survivors 88% make a total or near-total recovery. After several months, two thirds of the cases has resolution ("recanalisation") of the clot. The rate of recurrence was low (2.8%).[24]

In children with CVST the risk of death is high.[25] Poor outcome is more likely if a child with CVST develops seizures or has evidence of venous infarction on imaging.[26]

Epidemiology[edit]

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis is rare, with an estimated 3-4 cases per million annual incidence in adults. While it may occur in all age groups, it is most common in the third decade. 75% are female.[7] Given that older studies show no difference in incidence between men and women, it has been suggested that the use of oral contraceptives in women is behind the disparity between the sexes.[3] A 1995 report from Saudi Arabia found a substantially larger incidence at 7 cases per 100,000; this was attributed to the fact that Behçet's disease, which increases risk of CVST, is more common in the Middle East.[27]

A 1973 report found that CVST could be found on autopsy (examination of the body after death) in nine percent of all people. Many of these were elderly and had neurological symptoms in the period leading up to their death, and many developed concomitant heart failure.[28] An estimated 0.3% incidence of CVST in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2.[14]

In children, a Canadian study reported in 2001 that CVST occurs in 6.7 per million annually. 43% occur in the newborn (less than one month old), and a further 10% in the first year of life. Of the newborn, 84% were already ill, mostly from complications after childbirth and dehydration.[26]

Notable cases[edit]

U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton was hospitalized on December 30, 2012, for anticoagulation treatment of venous thrombosis of the right transverse sinus, which is located at the base of the brain. Clinton's thrombotic episode was discovered on an MRI scan done for follow-up of a cerebral concussion she had sustained 2.5 weeks previously, when she fell while suffering from gastroenteritis.[46]