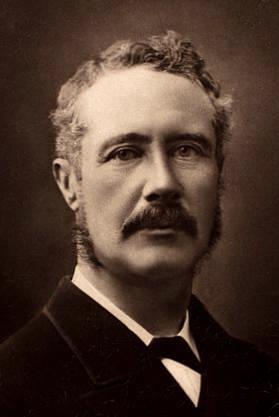

Charles George Gordon

Major-General Charles George Gordon CB (28 January 1833 – 26 January 1885), also known as Chinese Gordon, Gordon Pasha, and Gordon of Khartoum, was a British Army officer and administrator. He saw action in the Crimean War as an officer in the British Army. However, he made his military reputation in China, where he was placed in command of the "Ever Victorious Army", a force of Chinese soldiers led by European officers which was instrumental in putting down the Taiping Rebellion, regularly defeating much larger forces. For these accomplishments, he was given the nickname "Chinese Gordon" and honours from both the Emperor of China and the British.

Charles George Gordon

Chinese Gordon, Gordon Pasha, Gordon of Khartoum

26 January 1885 (aged 51)

Khartoum, Mahdist Sudan

United Kingdom

1852–1885

- Companion of the Order of the Bath (United Kingdom)

- Order of the Osmanieh, Fourth Class (Ottoman Empire)

- Order of the Medjidie, Fourth Class (Ottoman Empire)

- Chevalier of the Legion of Honour (France)

- Order of the Double Dragon (China)

- Imperial yellow jacket (China)

He entered the service of the Khedive of Egypt in 1873 (with British government approval) and later became the Governor-General of the Sudan, where he did much to suppress revolts and the local slave trade. He then resigned and returned to Europe in 1880.

A serious revolt then broke out in the Sudan, led by a Muslim religious leader and self-proclaimed Mahdi, Muhammad Ahmad. In early 1884, Gordon was sent to Khartoum with instructions to secure the evacuation of loyal soldiers and civilians and to depart with them. In defiance of those instructions, after evacuating about 2,500 civilians, he retained a smaller group of soldiers and non-military men. In the months before the fall of Khartoum, Gordon and the Mahdi corresponded; Gordon offered him the sultanate of Kordofan and the Mahdi requested Gordon to convert to Islam and join him, which Gordon declined. Besieged by the Mahdi's forces, Gordon organised a citywide defence that lasted for almost a year and gained him the admiration of the British public, but not of the government, which had wished him not to become entrenched there. Only when public pressure to act had become irresistible did the government, with reluctance, send a relief force. It arrived two days after the city had fallen and Gordon had been killed.

Early life[edit]

Gordon was born in Woolwich, Kent, a son of Major General Henry William Gordon (1786–1865) and Elizabeth (1792–1873), daughter of Samuel Enderby Junior. The men of the Gordon family had served as officers in the British Army for four generations, and as a son of a general, Gordon was raised to be the fifth generation; the possibility that Gordon would pursue anything other than a military career seems never to have been considered by his parents.[1] All of Gordon's brothers also became Army officers.[1]

Gordon grew up in England, Ireland, Scotland, and the Ionian Islands (which were under British rule until 1864) as his father was moved from post to post.[2] He was educated at Fullands School in Taunton, Taunton School, and the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich.[3]

In 1843, Gordon was devastated when his favourite sibling, his sister Emily, died of tuberculosis, writing years later, "humanly speaking it changed my life, it was never the same since".[4] After her death, her place as Gordon's favourite sibling was taken by his very religious older sister Augusta, who nudged her brother towards religion.[5]

As a teenager and an army officer cadet, Gordon was known for his high spirits, a combative streak, and tendency to disregard authority and the rules if he felt them to be stupid or unjust, a personality trait that held back his graduation by two years when teachers decided to punish him for flouting the rules.[6]

As a cadet, Gordon displayed exceptional talents at map-making and in designing fortifications, which led to his career choice of the Royal Engineers or "sappers" in the Army.[7] He was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Royal Engineers on 23 June 1852,[8] completing his training at Chatham, and he was promoted to full lieutenant on 17 February 1854.[9] The sappers were an elite corps who performed reconnaissance work, led storming parties, demolished obstacles in assaults, and undertook rear-guard actions in retreats and other hazardous tasks.[10]

As an officer, Gordon showed strong charisma and leadership, but his superiors distrusted him on account of his tendency to disobey orders if he felt them to be wrong or unjust.[7] A man of medium stature, with striking blue eyes, the charismatic Gordon had the ability to inspire men to follow him anywhere.[11]

Gordon was first assigned to construct fortifications at Milford Haven, Pembrokeshire, Wales. During his time in Milford Haven, Gordon was befriended by a young couple, Francis and Anne Drew, who introduced him to evangelical Protestantism.[12] Gordon was especially impressed with Philippians 1:21 where St. Paul wrote: "For to me, to live is Christ, and to die is gain", a passage he underlined in his Bible and often quoted.[12] He attended diverse congregations, including Roman Catholic, Baptist, Presbyterian, and Methodist. Gordon, who once said to a Roman Catholic priest that "the church is like the British Army, one army but many regiments", never aligned himself with or became a member of any church.[13]

Service with the Khedive[edit]

From the Danube to the Nile[edit]

In October 1871, he was appointed British representative on the international commission to maintain the navigation of the mouth of the River Danube, with headquarters at Galatz. Gordon was bored with the work of the Danube commission, and spent as much time as possible exploring the Romanian countryside, whose beauty enchanted Gordon when he was not making visits to Bucharest to meet up with his old friend Romolo Gessi, who was living there at the time.[58] During his second trip to Romania, Gordon insisted on living with ordinary people as he travelled over the countryside, commenting that Romanian peasants "live like animals with no fuel, but reeds", and spent one night at the home of a poor Jewish craftsman whom Gordon praised for his kindness in sharing the single bedroom with his host, his wife, and their seven children.[59] Gordon seemed pleased by his simple lifestyle, writing in a letter that: "One night, I slept better than I have for a long time, by a fire in a fisherman's hut".[59]

During a visit to Bulgaria, Gordon and Gessi become involved in an incident when a Bulgarian couple told them that their 17-year-old daughter had been abducted into the harem of an Ottoman pasha, and asked them to free their daughter.[60] Popular legend has it that Gordon and Gessi broke into the pasha's palace at night to rescue the girl, but the truth is less dramatic.[60] Gordon and Gessi demanded that Ahmed Pasha allow them to meet the girl alone, had their request granted after much arm-twisting, and then met the girl, who ultimately revealed she wanted to go home.[61] Gordon and Gessi threatened to go to the British and Italian press if she was not released at once, a threat that proved sufficient to win the girl her freedom.[61]

Gordon was promoted to colonel on 16 February 1872.[62] In 1872, Gordon was sent to inspect the British military cemeteries in the Crimea, and when passing through Constantinople, he made the acquaintance of the Prime Minister of Egypt, Raghib Pasha. The Egyptian Prime Minister opened negotiations for Gordon to serve under the Ottoman Khedive, Isma'il Pasha, who was popularly called "Isma'il the Magnificent" on the account of his lavish spending. In 1869, Isma'il spent 2 million Egyptian pounds (the equivalent to $300 million U.S. dollars in today's money) just on the party to celebrate the opening of the Suez Canal, in what was described as the party of the century.[63] In 1873, Gordon received a definite offer from the Khedive, which he accepted with the consent of the British government, and proceeded to Egypt early in 1874. After meeting Gordon in 1874, the Khedive Isma'il had said: "What an extraordinary Englishman! He doesn't want money!".[64]

The French-educated Isma'il Pasha greatly admired Europe as the model for excellence in everything, being an especially passionate Italophile and Francophile, saying at the beginning of his reign: "My country is no longer in Africa, it is now in Europe".[65] Isma'il was a Muslim who loved Italian wine and French champagne, and many of his more conservative subjects in Egypt and the Sudan felt alienated by a regime that was determined to Westernise the country with little regard for tradition.[65] The languages of Khedive's court were Turkish and French, not Arabic. The Khedive's great dream was to make Egypt culturally a part of Europe, and he spent huge sums of money attempting to modernise and Westernise Egypt, in the process going very deeply into debt.[66]

At the beginning of his reign in 1863, Egypt's debt had been 3 million Egyptian pounds. When Isma'il's reign ended in 1879, Egypt's debt had risen to 93 million pounds.[67] During the American Civil War, when the Union blockade had cut off the American South from the world economy, the price of Egyptian cotton, known as "white gold" had skyrocketed as British textile mills turned to Egypt as an alternative source of cotton, causing an economic blossoming of Egypt that ended abruptly in 1865.[66] As the attempts of his grandfather—Muhammad Ali the Great—to depose the ruling Ottoman family in favour of his own family had failed due to the opposition of Russia and Britain, the imperialistic Ismai'il had turned his attention southwards and was determined to build an Egyptian empire in Africa, planning on subjugating the Great Lakes region and the Horn of Africa.[68] As part of his Westernisation programme, Isma'il often hired Westerners to work in his government both in Egypt and in the Sudan. Ismai'il's Chief of General Staff was the American general Charles Pomeroy Stone, and other veterans of the American Civil War were commanding Egyptian troops.[69] Urban wrote that most of the Westerners in Egyptian pay were "misfits" who took up Egyptian service because they were unable to get ahead in their own nations.[70]

Typical of the men that Khedive Isma'il Pasha hired was Valentine Baker, a British Army officer dishonorably discharged after being convicted of raping a young woman in England that he had been asked to chaperon. After Baker's release from prison, Isma'il hired him to work in the Sudan.[71] John Russell, the son of the famous war correspondent William Howard Russell, was another European recruited to serve on Gordon's staff.[72] The younger Russell was described by his own father as an alcoholic and spendthrift who "was beyond help" as it was always the "same story-idleness, self-indulgence, gambling, and constant promises" broken time after time, leading his father to get him a job in the Sudan, where his laziness infuriated Gordon to no end.[72]

Personal life[edit]

Personal beliefs[edit]

Gordon had been born into the Church of England, but he never quite trusted the Anglican Church, instead preferring his own personal brand of Protestantism.[91] In his worn-out state, Gordon had some sort of religious rebirth, leading him to write to his sister Augusta: "Through the workings of Christ in my body by His Body and Blood, the medicine worked. Ever since the realisation of the sacrament, I have been turned upside down".[202] The eccentric Gordon was very religious, but he departed from Christian orthodoxy on a number of points. Gordon believed in reincarnation. In 1877, he wrote in a letter: "This life is only one of a series of lives which our incarnated part has lived. I have little doubt of our having pre-existed; and that also in the time of our pre-existence we were actively employed. So, therefore, I believe in our active employment in a future life, and I like the thought."[203] Gordon was an ardent Christian cosmologist, who also believed that the Garden of Eden was on the island of Praslin in the Seychelles.[204] Gordon believed that God's throne from which He governed the universe rested upon the earth, which was further surrounded by the firmament.[11]

Gordon believed in both predestination—writing that, "I believe that not a worm is picked up by a bird without the direct intervention of God"—and free will with humans choosing their own fate, writing, "I cannot and do not pretend to reconcile the two".[205] These religious beliefs mirrored differing aspects of Gordon's personality as he believed that he could choose his own fate through the force of his personality and a fatalistic streak often ending his letters with D.V (Deo volente – Latin for "God willing", i.e. whatever God wants will be).[205] Gordon was well-known for sticking Christian tracts onto city walls and to throw them out of a train window.[11] The Romanian historian Eric Tappe described Gordon as a man who developed his own "very personal peculiar variety of Protestantism".[59]

Personality[edit]

In his book Eminent Victorians, Lytton Strachey portrays Gordon in the following manner:[206]