Chicano Movement

The Chicano Movement, also referred to as El Movimiento, was a social and political movement in the United States that worked to embrace a Chicano/a identity and worldview that combated structural racism, encouraged cultural revitalization, and achieved community empowerment by rejecting assimilation.[1][2] Chicanos also expressed solidarity and defined their culture through the development of Chicano art during El Movimiento, and stood firm in preserving their religion.[3]

Chicano Movement

1940s to 1970s

(continued activism by Chicano groups)

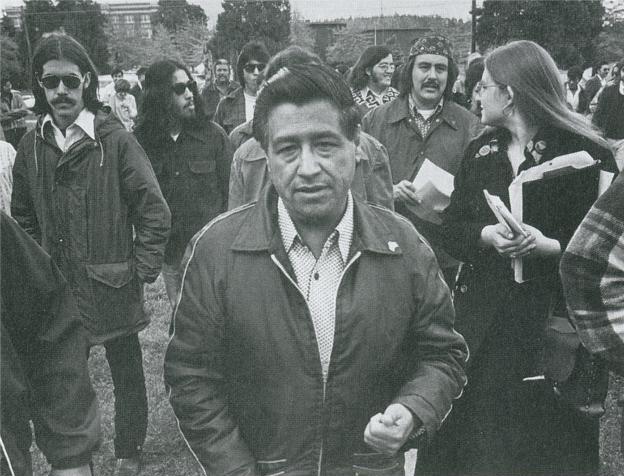

The Chicano Movement was influenced by and entwined with the Black power movement, and both movements held similar objectives of community empowerment and liberation while also calling for Black–Brown unity.[4][5] Leaders such as César Chávez, Reies Tijerina, and Rodolfo Gonzales learned strategies of resistance and worked with leaders of the Black Power movement. Chicano organizations like the Brown Berets and Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO) were influenced by the political agenda of Black activist organizations such as the Black Panthers. Chicano political demonstrations, such as the East L.A. walkouts and the Chicano Moratorium, occurred in collaboration with Black students and activists.[4][2]

Similar to the Black Power movement, the Chicano Movement experienced heavy state surveillance, infiltration, and repression from U.S. government informants and agent provocateurs through organized activities such as COINTELPRO. Movement leaders like Rosalio Muñoz were ousted from their positions of leadership by government agents, organizations such as MAYO and the Brown Berets were infiltrated, and political demonstrations such as the Chicano Moratorium became sites of police brutality, which led to the decline of the movement by the mid-1970s.[6][7][8][9]

Other reasons for the movement's decline include its centering of the masculine subject, which marginalized and excluded Chicanas,[10][11][12] and a growing disinterest in Chicano nationalist constructs such as Aztlán.[13]

Etymology[edit]

Before this, Chicano/a had been a term of derision, adopted by some Pachucos as an expression of defiance to Anglo-American society.[14] With the rise of Chicanismo, Chicano/a became a reclaimed term in the 1960s and 1970s, used to express political autonomy, ethnic and cultural solidarity, and pride in being of Indigenous descent, diverging from the assimilationist Mexican-American identity.[15][16][17]

Central Americans in the Chicano Movement[edit]

The Chicano Movement was not only limited to Mexican-American individuals. Central Americans also participated in the movement, often identifying themselves as Chicano. In the 1960s, the Central American population comprised approximately 50,000 across the United States.[34] In California, Central Americans migrated and concentrated in cities like San Jose, San Francisco, and Los Angeles.[35] Similar to Mexican Americans, Central Americans faced issues in the United States such as discrimination, lack of access to education and healthcare, and low-wage jobs.[36] The difference is that Central American activists have called for the inclusion of Central American issues and experiences within the broader movement. The Central American diaspora have faced discrimination and mistreatment in the United States, particularly from other Latinos because of their identity.[37]

The effects of the Chicano Movement are still felt by Central Americans in the modern times. For instance, many of the MEChA chapters that were established during the movement have started to rename the organization. The Los Angeles Times reported on leaders in the Garfield High School chapter deciding to avoid mentioning the word "Chicano" or "Aztlán," since they explained that the names were Mexican-centric and excluded identities.[38]

In academia, there is a movement to expand ChicanX-LatinX departments to include Central American Studies. Cal-State Northridge became the first university to establish a Central American Studies Department in the United States. In 2019, students at University of California, Los Angeles organized for their Chicana/o Studies Department to expand and include Central American Studies. Most recently, East Los Angeles College added a Central American Studies major, being the first community college to do so. South American departments and majors have to be realized.[39][40]

Geography[edit]

Scholars have paid some attention to the geography of the movement and situate the Southwest as the epicenter of the struggle. However, in examining the struggle's activism, maps allow us to see that activity was not spread evenly through the region and that certain organizations and types of activism were limited to particular geographies.[41] For instance, in southern Texas where Mexican Americans comprised a significant portion of the population and had a history of electoral participation, the Raza Unida Party started in 1970 by Jose Angel Gutierrez hoped to win elections and mobilize the voting power of Chicanos. RUP thus became the focus of considerable Chicano activism in Texas in the early 1970s.

The movement in California took a different shape, less concerned about elections. Chicanos in Los Angeles formed alliances with other oppressed people who identified with the Third World Left and were committed to toppling U.S. imperialism and fighting racism. The Brown Berets, with links to the Black Panther Party, was one manifestation of the multiracial context in Los Angeles. The Chicano Moratorium antiwar protests of 1970 and 1971 also reflected the vibrant collaboration between African Americans, Japanese Americans, American Indians, and white antiwar activists that had developed in Southern California.

Chicano student activism also followed particular geographies. MEChA established in Santa Barbara, California, in 1969, united many university and college Mexican American groups under one umbrella organization. MEChA became a multi-state organization, but an examination of the year-by-year expansion shows a continued concentration in California. The Mapping American Social Movements digital project shows maps and charts demonstrating that as the organization added dozens then hundreds of chapters, the vast majority were in California. This should cause scholars to ask what conditions made the state unique, and why Chicano students in other states were less interested in organizing MEChA chapters.

Anti-war activism[edit]

The Chicano Moratorium was a movement by Chicano activists that organized anti-Vietnam War demonstrations and activities throughout the Southwest and other Mexican American communities from November 1969 through August 1971. The movement focused on the disproportionately high death rate of Mexican American soldiers in Vietnam as well as the discrimination faced at home.[62] After months of demonstrations and conferences, it was decided to hold a National Chicano Moratorium demonstration against the war on August 29, 1970. The march began at Belvedere Park in LA and headed towards Laguna Park alongside 20,000 to 30,000 people. The Committee members included Rosalio Muñoz and Corky Gonzales and only lasted one more year, but the political momentum generated by the Moratorium led many of its activists to continue their activism in other groups.[63] The rally became violent when there was a disturbance in Laguna Park. There were people of all ages at the rally because it was intended to be a peaceful event. The sheriffs who were there later claimed that they were responding to an incident at a nearby liquor store that involved Chicanos who had allegedly stolen some drinks.[64] The sheriffs also added that upon their arrival they were hit with cans and stones. Once the sheriff arrived, they claimed the rally to be an "unlawful assembly" which turned violent. Tear gas and mace were everywhere, demonstrators were hit by billy clubs and arrested as well. The event that took place was being referred to as a riot, some have gone as far to call it a "Police Riot" to emphasize that the police were the ones who initiated it.[64]

The LA Protest brought many chicanos together and got support from other areas like Denver, Colorado who brought one hundred members and affiliates. On August 29, 1970 this was the largest rebellious movement of minorities since Watts uprising of (1965). More than 150 people were arrested and four were killed some accidental. A report from the Los Angeles Times stated, Gustav Montag got in direct contact with the police when they began opening fire in an alley and Gustav's defense was to throw broken pieces of concrete at the officers. The article stated the police officers were aiming over his head in attempts to scare him off. Montag was pictured being carried away from the scene by several brothers and was later announced dead at the scene. Montag was a Sephardic Jew who supported the movement.

Chicano press[edit]

The Chicano press disseminated Chicano history, literature, and current news.[72] The press created a link between the core and the periphery to create a national Chicano identity and community. The Chicano Press Association (CPA) created in 1969 was significant to the development of this national ethos. The CPA argued that an active press was foundational to the liberation of Chicano people, and represented about twenty newspapers, mostly in California but also throughout the Southwest.

Chicanos at many colleges campuses also created their own student newspapers, but many ceased publication within a year or two, or merged with other larger publications. Organizations such as the Brown Berets and MECHA also established their own independent newspapers. Chicano communities published newspapers like El Grito del Norte from Denver and Caracol from San Antonio, Texas.

Over 300 newspapers and periodicals in both large and small communities have been linked to the Movement.[73]

Chicano religion[edit]

Many in the Chicano Movement were influenced by their Catholic identities. Cesar Chávez heavily relied on Catholic influence and practices. Fasting was common by many activists though who would only break their fasts to consume communion.[74] The Virgin of Guadalupe was also used as a symbol of inspiration during many protests.[75] The Chicano Movement was often inspired by their religious convictions to continue the tradition of commitment to social change and asserting their rights. There was also influence from indigenous forms of religion combined with Catholic beliefs. Altars would be set up by the matriarchs of families that often included both Catholic symbols and indigenous religious symbols.[76] Both Catholic beliefs and the inclusion of indigenous religious practices were influenced many in the Chicano Movement to continue their protests and fight to equality.[77]