Cholera

Cholera (/ˈkɒlərə/) is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium Vibrio cholerae.[4][3] Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe.[3] The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea lasting a few days.[2] Vomiting and muscle cramps may also occur.[3] Diarrhea can be so severe that it leads within hours to severe dehydration and electrolyte imbalance.[2] This may result in sunken eyes, cold skin, decreased skin elasticity, and wrinkling of the hands and feet.[5] Dehydration can cause the skin to turn bluish.[8] Symptoms start two hours to five days after exposure.[3]

This article is about the bacterial disease. For the dish, see Cholera (food).Cholera

Asiatic cholera, epidemic cholera[1]

Large amounts of watery diarrhea, vomiting, muscle cramps[2][3]

2 hours to 5 days after exposure[3]

A few days[2]

Vibrio cholerae spread by fecal-oral route[2][4]

Poor sanitation, not enough clean drinking water, poverty[2]

Improved sanitation, clean water, hand washing, cholera vaccines[2][5]

Less than 1% mortality rate with proper treatment, untreated mortality rate 50–60%

3–5 million people a year[2]

28,800 (2015)[7]

Cholera is caused by a number of types of Vibrio cholerae, with some types producing more severe disease than others.[2] It is spread mostly by unsafe water and unsafe food that has been contaminated with human feces containing the bacteria.[2] Undercooked shellfish is a common source.[9] Humans are the only known host for the bacteria.[2] Risk factors for the disease include poor sanitation, insufficient clean drinking water, and poverty.[2] Cholera can be diagnosed by a stool test,[2] or a rapid dipstick test, although the dipstick test is less accurate.[10]

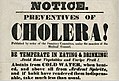

Prevention methods against cholera include improved sanitation and access to clean water.[5] Cholera vaccines that are given by mouth provide reasonable protection for about six months, and confer the added benefit of protecting against another type of diarrhea caused by E. coli.[2] In 2017 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a single-dose, live, oral cholera vaccine called Vaxchora for adults aged 18–64 who are travelling to an area of active cholera transmission.[11] It offers limited protection to young children. People who survive an episode of cholera have long-lasting immunity for at least three years (the period tested).[12]

The primary treatment for affected individuals is oral rehydration salts (ORS), the replacement of fluids and electrolytes by using slightly sweet and salty solutions.[2] Rice-based solutions are preferred.[2] In children, zinc supplementation has also been found to improve outcomes.[6] In severe cases, intravenous fluids, such as Ringer's lactate, may be required, and antibiotics may be beneficial.[2] The choice of antibiotic is aided by antibiotic sensitivity testing.[3]

Cholera continues to affect an estimated 3–5 million people worldwide and causes 28,800–130,000 deaths a year.[2][7] To date, seven cholera pandemics have occurred in the developing world, with the most recent beginning in 1961, and continuing today.[13] The illness is rare in high-income countries, and affects children most severely.[2][14] Cholera occurs as both outbreaks and chronically in certain areas.[2] Areas with an ongoing risk of disease include Africa and Southeast Asia.[2] The risk of death among those affected is usually less than 5%, given improved treatment, but may be as high as 50% without such access to treatment.[2] Descriptions of cholera are found as early as the 5th century BC in Sanskrit.[5] In Europe, cholera was a term initially used to describe any kind of gastroenteritis, and was not used for this disease until the early 19th century.[15] The study of cholera in England by John Snow between 1849 and 1854 led to significant advances in the field of epidemiology because of his insights about transmission via contaminated water, and a map of the same was the first recorded incidence of epidemiological tracking.[5][16]

Diagnosis

A rapid dipstick test is available to determine the presence of V. cholerae.[38] In those samples that test positive, further testing should be done to determine antibiotic resistance.[38] In epidemic situations, a clinical diagnosis may be made by taking a patient history and doing a brief examination. Treatment via hydration and over-the-counter hydration solutions can be started without or before confirmation by laboratory analysis, especially where cholera is a common problem.[41]

Stool and swab samples collected in the acute stage of the disease, before antibiotics have been administered, are the most useful specimens for laboratory diagnosis. If an epidemic of cholera is suspected, the most common causative agent is V. cholerae O1. If V. cholerae serogroup O1 is not isolated, the laboratory should test for V. cholerae O139. However, if neither of these organisms is isolated, it is necessary to send stool specimens to a reference laboratory.

Infection with V. cholerae O139 should be reported and handled in the same manner as that caused by V. cholerae O1. The associated diarrheal illness should be referred to as cholera and must be reported in the United States.[42]

Prognosis

If people with cholera are treated quickly and properly, the mortality rate is less than 1%; however, with untreated cholera, the mortality rate rises to 50–60%.[17][1]

For certain genetic strains of cholera, such as the one present during the 2010 epidemic in Haiti and the 2004 outbreak in India, death can occur within two hours of becoming ill.[83]

Society and culture

Health policy

In many developing countries, cholera still reaches its victims through contaminated water sources, and countries without proper sanitation techniques have greater incidence of the disease.[134] Governments can play a role in this. In 2008, for example, the Zimbabwean cholera outbreak was due partly to the government's role, according to a report from the James Baker Institute.[22] The Haitian government's inability to provide safe drinking water after the 2010 earthquake led to an increase in cholera cases as well.[135]

Similarly, South Africa's cholera outbreak was exacerbated by the government's policy of privatizing water programs. The wealthy elite of the country were able to afford safe water while others had to use water from cholera-infected rivers.[136]

According to Rita R. Colwell of the James Baker Institute, if cholera does begin to spread, government preparedness is crucial. A government's ability to contain the disease before it extends to other areas can prevent a high death toll and the development of an epidemic or even pandemic. Effective disease surveillance can ensure that cholera outbreaks are recognized as soon as possible and dealt with appropriately. Oftentimes, this will allow public health programs to determine and control the cause of the cases, whether it is unsanitary water or seafood that have accumulated a lot of Vibrio cholerae specimens.[22] Having an effective surveillance program contributes to a government's ability to prevent cholera from spreading. In the year 2000 in the state of Kerala in India, the Kottayam district was determined to be "Cholera-affected"; this pronouncement led to task forces that concentrated on educating citizens with 13,670 information sessions about human health.[137] These task forces promoted the boiling of water to obtain safe water, and provided chlorine and oral rehydration salts.[137] Ultimately, this helped to control the spread of the disease to other areas and minimize deaths. On the other hand, researchers have shown that most of the citizens infected during the 1991 cholera outbreak in Bangladesh lived in rural areas, and were not recognized by the government's surveillance program. This inhibited physicians' abilities to detect cholera cases early.[138]

According to Colwell, the quality and inclusiveness of a country's health care system affects the control of cholera, as it did in the Zimbabwean cholera outbreak.[22] While sanitation practices are important, when governments respond quickly and have readily available vaccines, the country will have a lower cholera death toll. Affordability of vaccines can be a problem; if the governments do not provide vaccinations, only the wealthy may be able to afford them and there will be a greater toll on the country's poor.[139][140] The speed with which government leaders respond to cholera outbreaks is important.[141]

Besides contributing to an effective or declining public health care system and water sanitation treatments, government can have indirect effects on cholera control and the effectiveness of a response to cholera.[142] A country's government can impact its ability to prevent disease and control its spread. A speedy government response backed by a fully functioning health care system and financial resources can prevent cholera's spread. This limits cholera's ability to cause death, or at the very least a decline in education, as children are kept out of school to minimize the risk of infection.[142] Inversely, poor government response can lead to civil unrest and cholera riots.[143]

Country examples

Zambia

In Zambia, widespread cholera outbreaks have occurred since 1977, most commonly in the capital city of Lusaka.[157] In 2017, an outbreak of cholera was declared in Zambia after laboratory confirmation of Vibrio cholerae O1, biotype El Tor, serotype Ogawa, from stool samples from two patients with acute watery diarrhea. There was a rapid increase in the number of cases from several hundred cases in early December 2017 to approximately 2,000 by early January 2018.[158] With intensification of the rains, new cases increased on a daily basis reaching a peak on the first week of January 2018 with over 700 cases reported.[159]

In collaboration with partners, the Zambia Ministry of Health (MoH) launched a multifaceted public health response that included increased chlorination of the Lusaka municipal water supply, provision of emergency water supplies, water quality monitoring and testing, enhanced surveillance, epidemiologic investigations, a cholera vaccination campaign, aggressive case management and health care worker training, and laboratory testing of clinical samples.[158]

The Zambian Ministry of Health implemented a reactive one-dose Oral Cholera Vaccine (OCV) campaign in April 2016 in three Lusaka compounds, followed by a pre-emptive second-round in December.[160]