Common sense

Common sense is sound, practical judgement concerning everyday matters, or a basic ability to perceive, understand, and judge in a manner that is shared by (i.e., "common to") nearly all people.[1]

Not to be confused with Common knowledge.

The everyday understanding of common sense is ultimately derived from historical philosophical discussions. Relevant terms from other languages used in such discussions include Latin sensus communis, Greek αἴσθησις κοινὴ (aísthēsis koinḕ), and French bon sens, but these are not straightforward translations in all contexts. Similarly in English, there are different shades of meaning, implying more or less education and wisdom. Notable, "good sense" is sometimes seen as equivalent to "common sense", and sometimes not.[2]

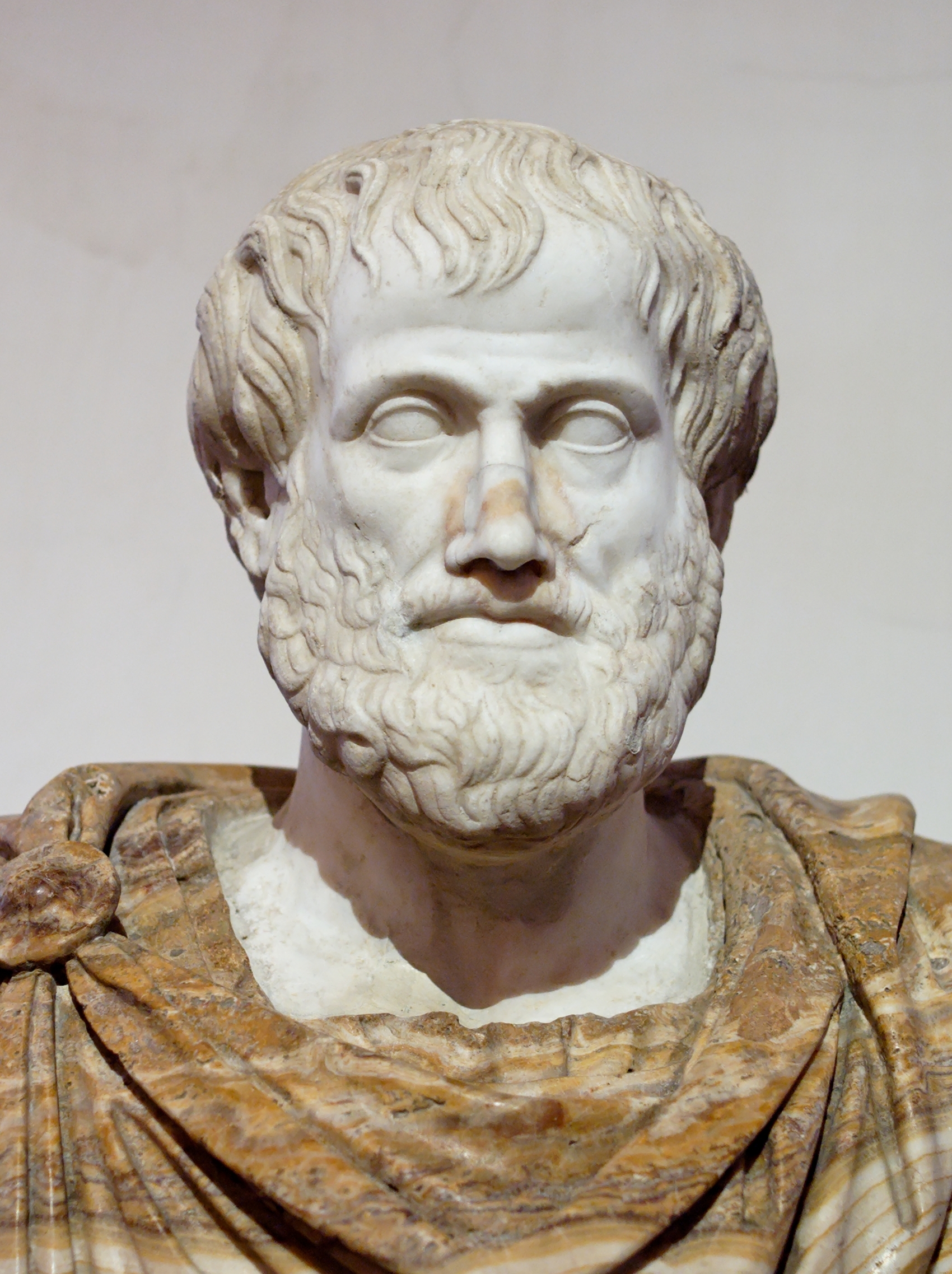

"Common sense" has at least two specific philosophical meanings. One is as a capability of the animal soul (ψῡχή, psūkhḗ), proposed by Aristotle to explain how the different senses join and enable discrimination of particular objects by people and other animals. This common sense is distinct from the several sensory perceptions and from human rational thought, but it cooperates with both. A second philosophical use of the term is Roman-influenced and is used for the natural human sensitivity for other humans and the community.[3]

Just like the everyday meaning, both of the philosophical meanings refer to a type of basic awareness and ability to judge that most people are expected to share naturally, even if they cannot explain why. All these meanings of "common sense", including the everyday ones, are interconnected in a complex history and have evolved during important political and philosophical debates in modern Western civilisation, notably concerning science, politics and economics.[4] The interplay between the meanings has come to be particularly notable in English, as opposed to other western European languages, and the English term has become international.[5]

In philosophical and scientific contexts, since the Age of Enlightenment the term "common sense" has been used for rhetorical effect both approvingly and disapprovingly. On the one hand it has been a standard for good taste and source of scientific and logical axioms. On the other hand it has been equated to vulgar prejudice and superstition.[6] It was at the beginning of the 18th century that this old philosophical term first acquired its modern English meaning: "Those plain, self-evident truths or conventional wisdom that one needed no sophistication to grasp and no proof to accept precisely because they accorded so well with the basic (common sense) intellectual capacities and experiences of the whole social body."[7] This began with Descartes's criticism of it, and what came to be known as the dispute between "rationalism" and "empiricism". In the opening line of one of his most famous books, Discourse on Method, Descartes established the most common modern meaning, and its controversies, when he stated that everyone has a similar and sufficient amount of common sense (bon sens), but it is rarely used well. Therefore, a skeptical logical method described by Descartes needs to be followed and common sense should not be overly relied upon.[8] In the ensuing 18th century Enlightenment, common sense came to be seen more positively as the basis for modern thinking. It was contrasted to metaphysics, which was, like Cartesianism, associated with the Ancien Régime. Thomas Paine's polemical pamphlet Common Sense (1776) has been described as the most influential political pamphlet of the 18th century, affecting both the American and French revolutions.[6] Today, the concept of common sense, and how it should best be used, remains linked to many of the most perennial topics in epistemology and ethics, with special focus often directed at the philosophy of the modern social sciences.

"Sensus communis" is the Latin translation of the Greek koinḕ aísthēsis, which came to be recovered by Medieval scholastics when discussing Aristotelian theories of perception. In the earlier Latin of the Roman empire, the term had taken a distinct ethical detour, developing new shades of meaning. These especially Roman meanings were apparently influenced by several Stoic Greek terms with the word koinḗ (κοινή, 'common, shared'); not only koinḕ aísthēsis, but also such terms as koinós noûs (κοινός νοῦς, 'common mind/thought/reason'), koinḗ énnoia (κοινή ἔννοιᾰ), and koinonoēmosúnē, all of which involve noûs—something, at least in Aristotle, that would not be present in "lower" animals.[29]

Another link between Latin communis sensus and Aristotle's Greek was in rhetoric, a subject that Aristotle was the first to systematize. In rhetoric, a prudent speaker must take account of opinions (δόξαι, dóxai) that are widely held.[32] Aristotle referred to such commonly held beliefs not as koinaí dóxai (κοιναί δόξαι, lit. ''common opinions''), which is a term he used for self-evident logical axioms, but with other terms such as éndóxa (ἔνδόξα).

In his Rhetoric for example Aristotle mentions "koinōn [...] tàs písteis" or "common beliefs", saying that "our proofs and arguments must rest on generally accepted principles, [...] when speaking of converse with the multitude".[33] In a similar passage in his own work on rhetoric, De Oratore, Cicero wrote that "in oratory the very cardinal sin is to depart from the language of everyday life and the usage approved by the sense of the community." The sense of the community is in this case one translation of "communis sensus" in the Latin of Cicero.[34][35]

Whether the Latin writers such as Cicero deliberately used this Aristotelian term in a new more peculiarly Roman way, probably also influenced by Greek Stoicism, therefore remains a subject of discussion. Schaeffer (1990, p. 112) has proposed for example that the Roman republic maintained a very "oral" culture whereas in Aristotle's time rhetoric had come under heavy criticism from philosophers such as Socrates. Peters Agnew (2008) argues, in agreement with Shaftesbury, that the concept developed from the Stoic concept of ethical virtue, influenced by Aristotle, but emphasizing the role of both the individual perception, and shared communal understanding. But in any case a complex of ideas attached itself to the term, to be almost forgotten in the Middle Ages, and eventually returning into ethical discussion in 18th-century Europe, after Descartes.

As with other meanings of common sense, for the Romans of the classical era "it designates a sensibility shared by all, from which one may deduce a number of fundamental judgments, that need not, or cannot, be questioned by rational reflection".[36] But even though Cicero did at least once use the term in a manuscript on Plato's Timaeus (concerning a primordial "sense, one and common for all [...] connected with nature"), he and other Roman authors did not normally use it as a technical term limited to discussion about sense perception, as Aristotle apparently had in De Anima, and as the Scholastics later would in the Middle Ages.[37] Instead of referring to all animal judgment, it was used to describe pre-rational, widely shared human beliefs, and therefore it was a near equivalent to the concept of humanitas. This was a term that could be used by Romans to imply not only human nature, but also humane conduct, good breeding, refined manners, and so on.[38] Apart from Cicero, Quintilian, Lucretius, Seneca, Horace and some of the most influential Roman authors influenced by Aristotle's rhetoric and philosophy used the Latin term "sensus communis" in a range of such ways.[39] As C. S. Lewis wrote:

Compared to Aristotle and his strictest medieval followers, these Roman authors were not so strict about the boundary between animal-like common sense and specially human reasoning. As discussed above, Aristotle had attempted to make a clear distinction between, on the one hand, imagination and the sense perception which both use the sensible koiná, and which animals also have; and, on the other hand, noûs (intellect) and reason, which perceives another type of koiná, the intelligible forms, which (according to Aristotle) only humans have. In other words, these Romans allowed that people could have animal-like shared understandings of reality, not just in terms of memories of sense perceptions, but in terms of the way they would tend to explain things, and in the language they use.[41]

The Enlightenment after Descartes[edit]

Epistemology: versus claims of certainty[edit]

During the Enlightenment, Descartes' insistence upon a mathematical-style method of thinking that treated common sense and the sense perceptions sceptically, was accepted in some ways, but also criticized. On the one hand, the approach of Descartes is and was seen as radically sceptical in some ways. On the other hand, like the Scholastics before him, while being cautious of common sense, Descartes was instead seen to rely too much on undemonstrable metaphysical assumptions in order to justify his method, especially in its separation of mind and body (with the sensus communis linking them). Cartesians such as Henricus Regius, Geraud de Cordemoy, and Nicolas Malebranche realized that Descartes's logic could give no evidence of the "external world" at all, meaning it had to be taken on faith.[53] Though his own proposed solution was even more controversial, Berkeley famously wrote that enlightenment requires a "revolt from metaphysical notions to the plain dictates of nature and common sense".[54] Descartes and the Cartesian "rationalists", rejected reliance upon experience, the senses and inductive reasoning, and seemed to insist that certainty was possible. The alternative to induction, deductive reasoning, demanded a mathematical approach, starting from simple and certain assumptions. This in turn required Descartes (and later rationalists such as Kant) to assume the existence of innate or "a priori" knowledge in the human mind—a controversial proposal.

In contrast to the rationalists, the "empiricists" took their orientation from Francis Bacon, whose arguments for methodical science were earlier than those of Descartes, and less directed towards mathematics and certainty. Bacon is known for his doctrine of the "idols of the mind", presented in his Novum Organum, and in his Essays described normal human thinking as biased towards believing in lies.[55] But he was also the opponent of all metaphysical explanations of nature, or over-reaching speculation generally, and a proponent of science based on small steps of experience, experimentation and methodical induction. So while agreeing upon the need to help common sense with a methodical approach, he also insisted that starting from common sense, including especially common sense perceptions, was acceptable and correct. He influenced Locke and Pierre Bayle, in their critique of metaphysics, and in 1733 Voltaire "introduced him as the "father" of the scientific method" to a French audience, an understanding that was widespread by 1750. Together with this, references to "common sense" became positive and associated with modernity, in contrast to negative references to metaphysics, which was associated with the Ancien Régime.[6]

As mentioned above, in terms of the more general epistemological implications of common sense, modern philosophy came to use the term common sense like Descartes, abandoning Aristotle's theory. While Descartes had distanced himself from it, John Locke abandoned it more openly, while still maintaining the idea of "common sensibles" that are perceived. But then George Berkeley abandoned both.[45] David Hume agreed with Berkeley on this, and like Locke and Vico saw himself as following Bacon more than Descartes. In his synthesis, which he saw as the first Baconian analysis of man (something the lesser known Vico had claimed earlier), common sense is entirely built up from shared experience and shared innate emotions, and therefore it is indeed imperfect as a basis for any attempt to know the truth or to make the best decision. But he defended the possibility of science without absolute certainty, and consistently described common sense as giving a valid answer to the challenge of extreme skepticism. Concerning such sceptics, he wrote:

Contemporary philosophy[edit]

Epistemology[edit]

Continuing the tradition of Reid and the enlightenment generally, the common sense of individuals trying to understand reality continues to be a serious subject in philosophy. In America, Reid influenced C. S. Peirce, the founder of the philosophical movement now known as Pragmatism, which has become internationally influential. One of the names Peirce used for the movement was "Critical Common-Sensism". Peirce, who wrote after Charles Darwin, suggested that Reid and Kant's ideas about inborn common sense could be explained by evolution. But while such beliefs might be well adapted to primitive conditions, they were not infallible, and could not always be relied upon.

Another example still influential today is from G. E. Moore, several of whose essays, such as the 1925 "A Defence of Common Sense", argued that individuals can make many types of statements about what they judge to be true, and that the individual and everyone else knows to be true. Michael Huemer has advocated an epistemic theory he calls phenomenal conservatism, which he claims to accord with common sense by way of internalist intuition.[80]

Ethics: what the community would think[edit]

In twentieth century philosophy the concept of the sensus communis as discussed by Vico and especially Kant became a major topic of philosophical discussion. The theme of this discussion questions how far the understanding of eloquent rhetorical discussion (in the case of Vico), or communally sensitive aesthetic tastes (in the case of Kant) can give a standard or model for political, ethical and legal discussion in a world where forms of relativism are commonly accepted, and serious dialogue between very different nations is essential. Some philosophers such as Jacques Rancière indeed take the lead from Jean-François Lyotard and refer to the "postmodern" condition as one where there is "dissensus communis".[81]

Hannah Arendt adapted Kant's concept of sensus communis as a faculty of aesthetic judgement that imagines the judgements of others, into something relevant for political judgement. Thus she created a "Kantian" political philosophy, which, as she said herself, Kant did not write. She argued that there was often a banality to evil in the real world, for example in the case of someone like Adolf Eichmann, which consisted in a lack of sensus communis and thoughtfulness generally. Arendt and also Jürgen Habermas, who took a similar position concerning Kant's sensus communis, were criticised by Lyotard for their use of Kant's sensus communis as a standard for real political judgement. Lyotard also saw Kant's sensus communis as an important concept for understanding political judgement, not aiming at any consensus, but rather at a possibility of a "euphony" in "dis-sensus". Lyotard claimed that any attempt to impose any sensus communis in real politics would mean imposture by an empowered faction upon others.[82]

In a parallel development, Antonio Gramsci, Benedetto Croce, and later Hans-Georg Gadamer took inspiration from Vico's understanding of common sense as a kind of wisdom of nations, going beyond Cartesian method. It has been suggested that Gadamer's most well-known work, Truth and Method, can be read as an "extended meditation on the implications of Vico's defense of the rhetorical tradition in response to the nascent methodologism that ultimately dominated academic enquiry".[83] In the case of Gadamer, this was in specific contrast to the sensus communis concept in Kant, which he felt (in agreement with Lyotard) could not be relevant to politics if used in its original sense.

Gadamer came into direct debate with his contemporary Habermas, the so-called Hermeneutikstreit. Habermas, with a self-declared Enlightenment "prejudice against prejudice" argued that if breaking free from the restraints of language is not the aim of dialectic, then social science will be dominated by whoever wins debates, and thus Gadamer's defense of sensus communis effectively defends traditional prejudices. Gadamer argued that being critical requires being critical of prejudices including the prejudice against prejudice. Some prejudices will be true. And Gadamer did not share Habermas' acceptance that aiming at going beyond language through method was not itself potentially dangerous. Furthermore, he insisted that because all understanding comes through language, hermeneutics has a claim to universality. As Gadamer wrote in the "Afterword" of Truth and Method, "I find it frighteningly unreal when people like Habermas ascribe to rhetoric a compulsory quality that one must reject in favor of unconstrained, rational dialogue".

Paul Ricoeur argued that Gadamer and Habermas were both right in part. As a hermeneutist like Gadamer he agreed with him about the problem of lack of any perspective outside of history, pointing out that Habermas himself argued as someone coming from a particular tradition. He also agreed with Gadamer that hermeneutics is a "basic kind of knowing on which others rest".[84] But he felt that Gadamer under-estimated the need for a dialectic that was critical and distanced, and attempting to go behind language.[85][86]

A recent commentator on Vico, John D. Schaeffer has argued that Gadamer's approach to sensus communis exposed itself to the criticism of Habermas because it "privatized" it, removing it from a changing and oral community, following the Greek philosophers in rejecting true communal rhetoric, in favour of forcing the concept within a Socratic dialectic aimed at truth. Schaeffer claims that Vico's concept provides a third option to those of Habermas and Gadamer and he compares it to the recent philosophers Richard J. Bernstein, Bernard Williams, Richard Rorty, and Alasdair MacIntyre, and the recent theorist of rhetoric, Richard Lanham.[87]

"Moral sense" as opposed to "rationality"[edit]

The other Enlightenment debate about common sense, concerning common sense as a term for an emotion or drive that is unselfish, also continues to be important in discussion of social science, and especially economics. The axiom that communities can be usefully modeled as a collection of self-interested individuals is a central assumption in much of modern mathematical economics, and mathematical economics has now come to be an influential tool of political decision making.

While the term "common sense" had already become less commonly used as a term for the empathetic moral sentiments by the time of Adam Smith, debates continue about methodological individualism as something supposedly justified philosophically for methodological reasons (as argued for example by Milton Friedman and more recently by Gary S. Becker, both members of the so-called Chicago school of economics).[88] As in the Enlightenment, this debate therefore continues to combine debates about not only what the individual motivations of people are, but also what can be known about scientifically, and what should be usefully assumed for methodological reasons, even if the truth of the assumptions are strongly doubted. Economics and social science generally have been criticized as a refuge of Cartesian methodology. Hence, amongst critics of the methodological argument for assuming self-centeredness in economics are authors such as Deirdre McCloskey, who have taken their bearings from the above-mentioned philosophical debates involving Habermas, Gadamer, the anti-Cartesian Richard Rorty and others, arguing that trying to force economics to follow artificial methodological laws is bad, and it is better to recognize social science as driven by rhetoric.