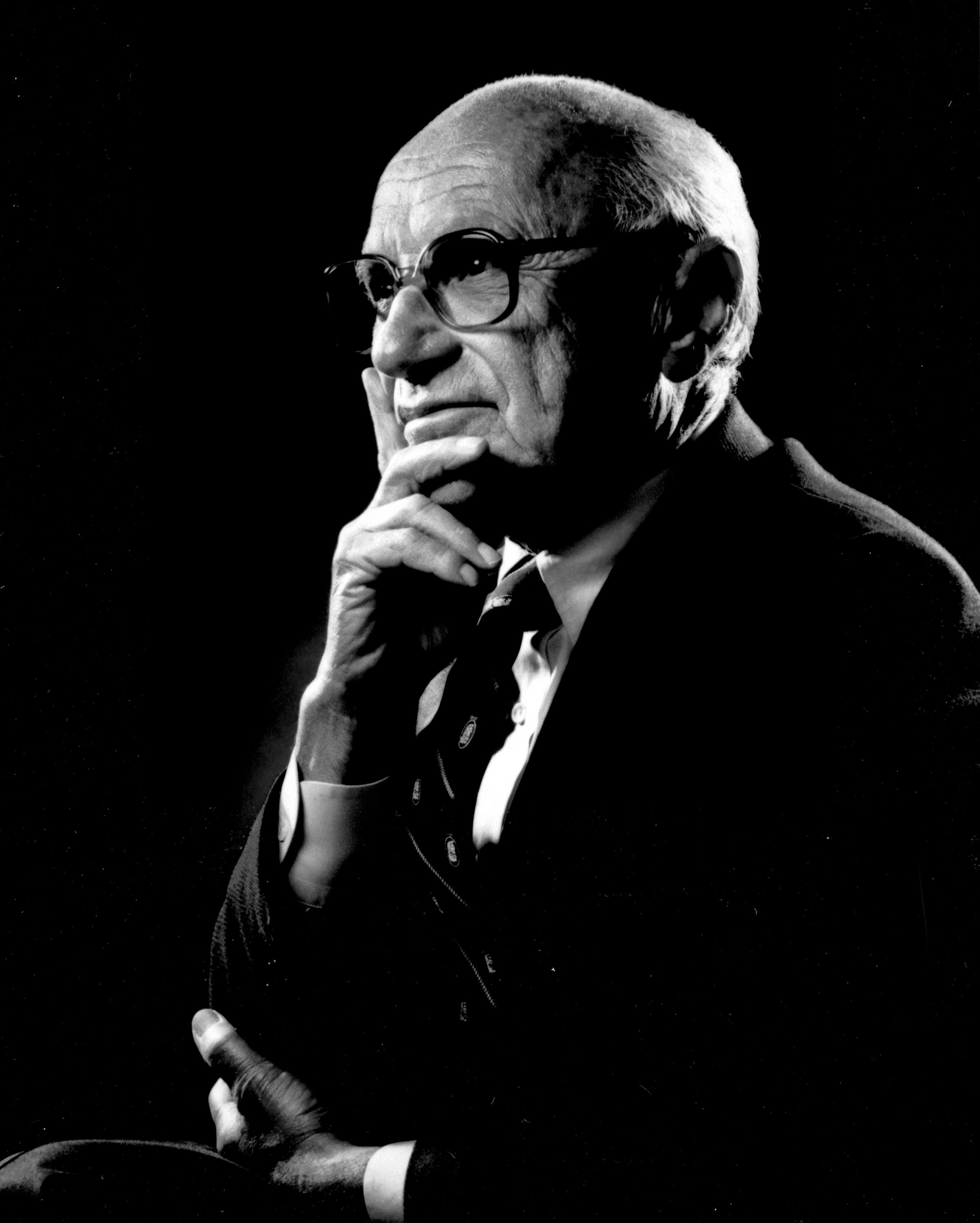

Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (/ˈfriːdmən/ ⓘ; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and the complexity of stabilization policy.[4] With George Stigler, Friedman was among the intellectual leaders of the Chicago school of economics, a neoclassical school of economic thought associated with the work of the faculty at the University of Chicago that rejected Keynesianism in favor of monetarism until the mid-1970s, when it turned to new classical macroeconomics heavily based on the concept of rational expectations.[5] Several students, young professors and academics who were recruited or mentored by Friedman at Chicago went on to become leading economists, including Gary Becker,[6] Robert Fogel,[7] and Robert Lucas Jr.[8]

Milton Friedman

July 31, 1912

November 16, 2006 (aged 94)

- National Resources Planning Board (1935–1937)

- National Bureau of Economic Research (1937–1940)

- Columbia University (1937–1941; 1943–1945; 1964–1965)

- University of Wisconsin, Madison (1940)

- U.S. Department of the Treasury (1941–1943)

- University of Chicago (1946–1977)

- University of Cambridge (1954–1955)

- Hoover Institution, Stanford University (1977–2006)

- Member of the American Philosophical Society (1957)[2]

- Member of the National Academy of Sciences (1973)

- National Medal of Science (1988)

- Presidential Medal of Freedom (1988)

- Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (1976)

- John Bates Clark Medal (1951)

Friedman's challenges to what he called "naive Keynesian theory"[9] began with his interpretation of consumption, which tracks how consumers spend. He introduced a theory which would later become part of mainstream economics and among the first to propagate the theory of consumption smoothing.[4][10] During the 1960s, he became the main advocate opposing Keynesian government policies,[11] and described his approach (along with mainstream economics) as using "Keynesian language and apparatus" yet rejecting its initial conclusions.[12] He theorized that there existed a natural rate of unemployment and argued that unemployment below this rate would cause inflation to accelerate.[a][13] He argued that the Phillips curve was in the long run vertical at the "natural rate" and predicted what would come to be known as stagflation.[14] Friedman promoted a macroeconomic viewpoint known as monetarism and argued that a steady, small expansion of the money supply was the preferred policy, as compared to rapid, and unexpected changes.[15] His ideas concerning monetary policy, taxation, privatization, and deregulation influenced government policies, especially during the 1980s. His monetary theory influenced the Federal Reserve's monetary policy in response to the global financial crisis of 2007–2008.[16]

After retiring from the University of Chicago in 1977, and becoming Emeritus professor in economics in 1983,[17] Friedman served as an advisor to Republican U.S. president Ronald Reagan and Conservative British prime minister Margaret Thatcher.[18] His political philosophy extolled the virtues of a free market economic system with minimal government intervention in social matters. He once stated that his role in eliminating conscription in the United States was his proudest achievement.[15] In his 1962 book Capitalism and Freedom, Friedman advocated policies such as a volunteer military, freely floating exchange rates, abolition of medical licenses, a negative income tax, school vouchers,[19] and opposition to the war on drugs and support for drug liberalization policies. His support for school choice led him to found the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice, later renamed EdChoice.[20][21]

Friedman's works cover a broad range of economic topics and public policy issues.[17] His books and essays have had global influence, including in former communist states.[22][23][24][25] A 2011 survey of economists commissioned by the EJW ranked Friedman as the second-most popular economist of the 20th century, following only John Maynard Keynes.[26] Upon his death, The Economist described him as "the most influential economist of the second half of the 20th century ... possibly of all of it".[27]

Early life[edit]

Friedman was born in Brooklyn, New York City on July 31, 1912. His parents, Sára Ethel (née Landau) and Jenő Saul Friedman, were Jewish working-class immigrants from Beregszász in Carpathian Ruthenia, Kingdom of Hungary (now Berehove in Ukraine).[28][29] They emigrated to America in their early teens.[28] They both worked as dry goods merchants. Friedman was their fourth child and only son, as well as the youngest of the children.[30] Shortly after his birth, the family relocated to Rahway, New Jersey.[31] Friedman's father, Jenő Saul Friedman, died during Friedman's senior year of high school, leaving Friedman and two older sisters to care for their mother.[28]

In his early teens, Friedman was injured in a car accident, which scarred his upper lip.[32][33] A talented student and an avid reader, Friedman graduated from Rahway High School in 1928, just before his 16th birthday.[30][34][35] He was the first in his family to attend a university. Friedman was awarded a competitive scholarship to Rutgers University and graduated in 1932.[36]

Friedman initially intended to become an actuary or mathematician, however, the state of the economy, which was at this point in a depression, convinced him to become an economist.[30][31] He was offered two scholarships to do graduate work, one in mathematics at Brown University and the other in economics at the University of Chicago.[37][38] Friedman chose the latter, earning a Master of Arts degree in 1933. He was strongly influenced by Jacob Viner, Frank Knight, and Henry Simons. Friedman met his future wife, economist Rose Director, while at the University of Chicago.[39]

During the 1933–1934 academic year, he had a fellowship at Columbia University, where he studied statistics with statistician and economist Harold Hotelling. He was back in Chicago for the 1934–1935 academic year, working as a research assistant for Henry Schultz, who was then working on Theory and Measurement of Demand.[40]

During the 1934–35 academic year, Friedman formed what would later prove to be lifetime friendships with George Stigler and W. Allen Wallis, both of whom later taught with Friedman at the University of Chicago.[41] Friedman was also influenced by two lifelong friends, Arthur Burns and Homer Johnson. They helped Friedman better understand the depth of economic thinking.[42]

Public service[edit]

Friedman was unable to find academic employment, so in 1935 he followed his friend W. Allen Wallis to Washington, D.C., where Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal was "a lifesaver" for many young economists.[43] At this stage, Friedman said he and his wife "regarded the job-creation programs such as the WPA, CCC, and PWA appropriate responses to the critical situation", but not "the price- and wage-fixing measures of the National Recovery Administration and the Agricultural Adjustment Administration".[44] Foreshadowing his later ideas, he believed price controls interfered with an essential signaling mechanism to help resources be used where they were most valued. Indeed, Friedman later concluded that all government intervention associated with the New Deal was "the wrong cure for the wrong disease", arguing the Federal Reserve was to blame, and that they should have expanded the money supply in reaction to what he later described in A Monetary History of the United States as "The Great Contraction".[45] Later, Friedman and his colleague Anna Schwartz wrote A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960, which argued that the Great Depression was caused by a severe monetary contraction due to banking crises and poor policy on the part of the Federal Reserve.[46] Robert J. Shiller describes the book as the "most influential account" of the Great Depression.[47]

During 1935, he began working for the National Resources Planning Board,[48] which was then working on a large consumer budget survey. Ideas from this project later became a part of his Theory of the Consumption Function, a book which first described consumption smoothing and the permanent income hypothesis. Friedman began employment with the National Bureau of Economic Research during the autumn of 1937 to assist Simon Kuznets in his work on professional income. This work resulted in their jointly authored publication Incomes from Independent Professional Practice, which introduced the concepts of permanent and transitory income, a major component of the permanent income hypothesis that Friedman worked out in greater detail in the 1950s. The book hypothesizes that professional licensing artificially restricts the supply of services and raises prices.[49]

Incomes from Independent Professional Practice remained quite controversial within the economics community because of Friedman's hypothesis that barriers to entry, which were exercised and enforced by the American Medical Association, led to higher than average wages for physicians, compared to other professional groups.[17][49] Barriers to entry are a fixed cost which must be incurred regardless of any outside factors such as work experience, or other factors of human capital.[50]

During 1940, Friedman was appointed as an assistant professor teaching economics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, but encountered anti semitism in the Economics department and returned to government service.[51][52] From 1941 to 1943 Friedman worked on wartime tax policy for the federal government, as an advisor to senior officials of the United States Department of the Treasury. As a Treasury spokesman during 1942, he advocated a Keynesian policy of taxation. He helped to invent the payroll withholding tax system, since the federal government needed money to fund the war.[53] He later said, "I have no apologies for it, but I really wish we hadn't found it necessary and I wish there were some way of abolishing withholding now."[54] In Milton and Rose Friedman's jointly written memoir, he wrote, "Rose has repeatedly chided me over the years about the role that I played in making possible the current overgrown government we both criticize so strongly."[53]

Academic career[edit]

Early years[edit]

In 1940 Friedman accepted a position at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, but left because of differences with faculty regarding United States involvement in World War II. Friedman believed the United States should enter the war.[55] In 1943, Friedman joined the Division of War Research at Columbia University (headed by W. Allen Wallis and Harold Hotelling), where he spent the rest of World War II working as a mathematical statistician, focusing on problems of weapons design, military tactics, and metallurgical experiments.[55][56]

In 1945 Friedman submitted Incomes from Independent Professional Practice (co-authored with Kuznets and completed during 1940) to Columbia as his doctoral dissertation. The university awarded him a PhD in 1946.[57][38] Friedman spent the 1945–1946 academic year teaching at the University of Minnesota (where his friend George Stigler was employed). On February 12, 1945, his only son, David D. Friedman, who would later follow in his father's footsteps as an economist, was born.[58]

University of Chicago[edit]

In 1946 Friedman accepted an offer to teach economic theory at the University of Chicago (a position opened by departure of his former professor Jacob Viner to Princeton University). Friedman would work for the University of Chicago for the next 30 years.[38] There he contributed to the establishment of an intellectual community that produced a number of Nobel Memorial Prize winners, known collectively as the Chicago school of economics.[31]

At the time, Arthur F. Burns, who was then the head of the National Bureau of Economic Research, and later chairman of the Federal Reserve, asked Friedman to rejoin the Bureau's staff.[59] He accepted the invitation, and assumed responsibility for the Bureau's inquiry into the role of money in the business cycle. As a result, he initiated the "Workshop in Money and Banking" (the "Chicago Workshop"), which promoted a revival of monetary studies. During the latter half of the 1940s, Friedman began a collaboration with Anna Schwartz, an economic historian at the Bureau, that would ultimately result in the 1963 publication of a book co-authored by Friedman and Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960.[15][31]

University of Cambridge[edit]

Friedman spent the 1954–1955 academic year as a Fulbright Visiting Fellow at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. At the time, the Cambridge economics faculty was divided into a Keynesian majority (including Joan Robinson and Richard Kahn) and an anti-Keynesian minority (headed by Dennis Robertson). Friedman speculated he was invited to the fellowship because his views were unacceptable to both of the Cambridge factions. Later his weekly columns for Newsweek magazine (1966–84) were well read and increasingly influential among political and business people,[60] and helped earn the magazine a Gerald Loeb Special Award in 1968.[61] From 1968 to 1978, he and Paul Samuelson participated in the Economics Cassette Series, a biweekly subscription series where the economist would discuss the days' issues for about a half-hour at a time.[62][63]

Public policy positions[edit]

Federal Reserve and monetary policy[edit]

Although Friedman concluded the government does have a role in the monetary system[124] he was critical of the Federal Reserve due to its poor performance and felt it should be abolished.[125][126][127] He was opposed to Federal Reserve policies, even during the so-called "Volcker shock" that was labeled "monetarist".[128] Friedman believed the Federal Reserve System should ultimately be replaced with a computer program.[129] He favored a system that would automatically buy and sell securities in response to changes in the money supply.[130]

The proposal to constantly grow the money supply at a certain predetermined amount every year has become known as Friedman's k-percent rule.[131] There is debate about the effectiveness of a theoretical money supply targeting regime.[132][133] The Fed's inability to meet its money supply targets from 1978 to 1982 led some to conclude it is not a feasible alternative to more conventional inflation and interest rate targeting.[134] Towards the end of his life, Friedman expressed doubt about the validity of targeting the quantity of money. To date, most countries have adopted inflation targeting instead of the k-percent rule.[135]

Idealistically, Friedman actually favored the principles of the 1930s Chicago plan, which would have ended fractional reserve banking and, thus, private money creation. It would force banks to have 100% reserves backing deposits, and instead place money creation powers solely in the hands of the US Government. This would make targeting money growth more possible, as endogenous money created by fractional reserve lending would no longer be a major issue.[131]

Friedman was a strong advocate for floating exchange rates throughout the entire Bretton-Woods period (1944–1971). He argued that a flexible exchange rate would make external adjustment possible and allow countries to avoid balance of payments crises. He saw fixed exchange rates as an undesirable form of government intervention. The case was articulated in an influential 1953 paper, "The Case for Flexible Exchange Rates", at a time when most commentators regarded the possibility of floating exchange rates as an unrealistic policy proposal.[136][137]