Constellation

A constellation is an area on the celestial sphere in which a group of visible stars forms a perceived pattern or outline, typically representing an animal, mythological subject, or inanimate object.[1]

This article is about the star grouping. For other uses, see Constellation (disambiguation).

The origins of the earliest constellations likely go back to prehistory. People used them to relate stories of their beliefs, experiences, creation, or mythology. Different cultures and countries invented their own constellations, some of which lasted into the early 20th century before today's constellations were internationally recognized. The recognition of constellations has changed significantly over time. Many changed in size or shape. Some became popular, only to drop into obscurity. Some were limited to a single culture or nation. Naming constellations also helped astronomers and navigators identify stars more easily.[2]

Twelve (or thirteen) ancient constellations belong to the zodiac (straddling the ecliptic, which the Sun, Moon, and planets all traverse). The origins of the zodiac remain historically uncertain; its astrological divisions became prominent c. 400 BC in Babylonian or Chaldean astronomy.[3] Constellations appear in Western culture via Greece and are mentioned in the works of Hesiod, Eudoxus and Aratus. The traditional 48 constellations, consisting of the Zodiac and 36 more (now 38, following the division of Argo Navis into three constellations) are listed by Ptolemy, a Greco-Roman astronomer from Alexandria, Egypt, in his Almagest. The formation of constellations was the subject of extensive mythology, most notably in the Metamorphoses of the Latin poet Ovid. Constellations in the far southern sky were added from the 15th century until the mid-18th century when European explorers began traveling to the Southern Hemisphere. Due to Roman and European transmission, each constellation has a Latin name.

In 1922, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) formally accepted the modern list of 88 constellations, and in 1928 adopted official constellation boundaries that together cover the entire celestial sphere.[4][5] Any given point in a celestial coordinate system lies in one of the modern constellations. Some astronomical naming systems include the constellation where a given celestial object is found to convey its approximate location in the sky. The Flamsteed designation of a star, for example, consists of a number and the genitive form of the constellation's name.

Other star patterns or groups called asterisms are not constellations under the formal definition, but are also used by observers to navigate the night sky. Asterisms may be several stars within a constellation, or they may share stars with more than one constellation. Examples of asterisms include the teapot within the constellation Sagittarius, or the big dipper in the constellation of Ursa Major.[6][7]

Terminology[edit]

The word constellation comes from the Late Latin term cōnstellātiō, which can be translated as "set of stars"; it came into use in Middle English during the 14th century.[8] The Ancient Greek word for constellation is ἄστρον (astron). These terms historically referred to any recognisable pattern of stars whose appearance was associated with mythological characters or creatures, earthbound animals, or objects.[1] Over time, among European astronomers, the constellations became clearly defined and widely recognised. Today, there are 88 IAU designated constellations.[9]

A constellation or star that never sets below the horizon when viewed from a particular latitude on Earth is termed circumpolar. From the North Pole or South Pole, all constellations south or north of the celestial equator are circumpolar. Depending on the definition, equatorial constellations may include those that lie between declinations 45° north and 45° south,[10] or those that pass through the declination range of the ecliptic or zodiac ranging between 23½° north, the celestial equator, and 23½° south.[11][12]

Stars in constellations can appear near each other in the sky, but they usually lie at a variety of distances away from the Earth. Since each star has its own independent motion, all constellations will change slowly over time. After tens to hundreds of thousands of years, familiar outlines will become unrecognizable.[13] Astronomers can predict the past or future constellation outlines by measuring individual stars' common proper motions or cpm[14] by accurate astrometry[15][16] and their radial velocities by astronomical spectroscopy.[17]

Identification[edit]

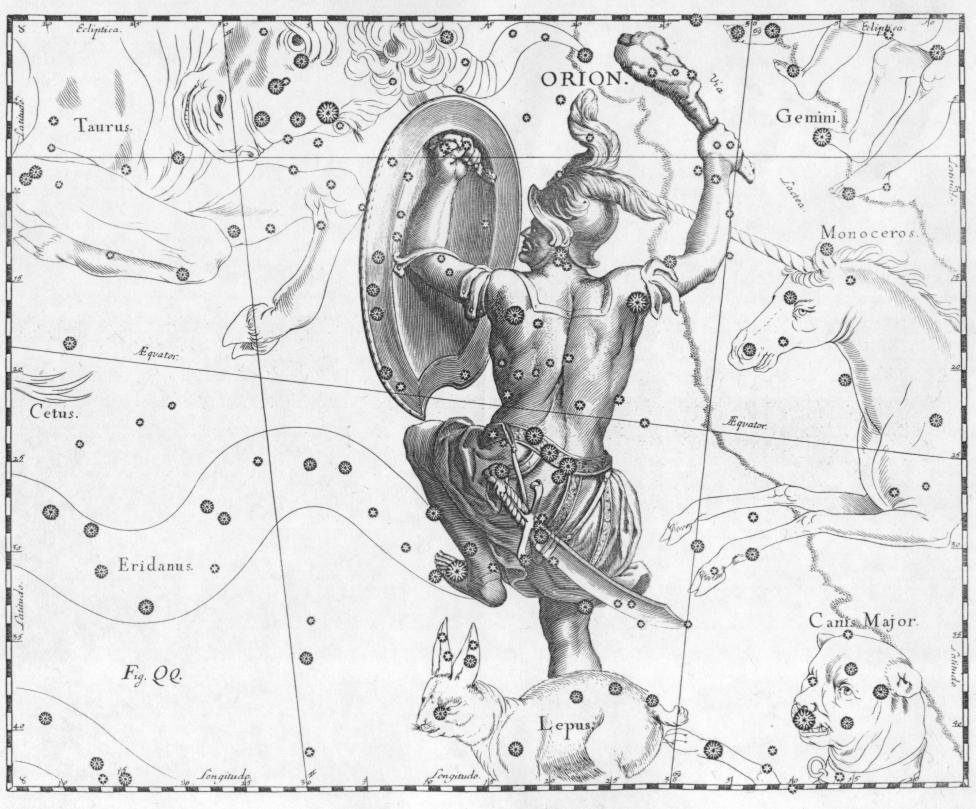

The 88 constellations recognized by the International Astronomical Union as well as those that cultures have recognized throughout history are imagined figures and shapes derived from the patterns of stars in the observable sky.[18] Many officially recognized constellations are based on the imaginations of ancient, Near Eastern and Mediterranean mythologies.[19] H.A. Rey, who wrote popular books on astronomy, pointed out the imaginative nature of the constellations and their mythological and artistic basis, and the practical use of identifying them through definite images, according to the classical names they were given.[20]

History of the early constellations[edit]

Lascaux Caves, southern France[edit]

It has been suggested that the 17,000-year-old cave paintings in Lascaux, southern France, depict star constellations such as Taurus, Orion's Belt, and the Pleiades. However, this view is not generally accepted among scientists.[21][22]

Mesopotamia[edit]

Inscribed stones and clay writing tablets from Mesopotamia (in modern Iraq) dating to 3000 BC provide the earliest generally accepted evidence for humankind's identification of constellations.[23] It seems that the bulk of the Mesopotamian constellations were created within a relatively short interval from around 1300 to 1000 BC. Mesopotamian constellations appeared later in many of the classical Greek constellations.[24]