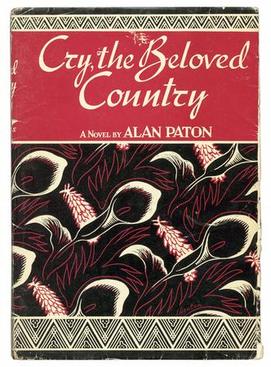

Cry, the Beloved Country

Cry, the Beloved Country is a 1948 novel by South African writer Alan Paton. Set in the prelude to apartheid in South Africa, it follows a black village priest and a white farmer who must deal with news of a murder.

This article is about the novel. For other uses, see Cry, the Beloved Country (disambiguation).Author

English

Johannesburg and Natal, 1940s

Scribners (USA) & Jonathan Cape (UK)

1 February 1948[1]

South Africa

256 (hardback ed., UK) 273 (hardback ed., US)

0-224-60578-X (hardback edition, UK)

823.914

PR9369.3 .P37

American publisher Bennett Cerf remarked at that year's meeting of the American Booksellers Association that there had been "only three novels published since the first of the year that were worth reading… Cry, The Beloved Country, The Ides of March, and The Naked and the Dead."[2] It remains one of the best-known works of South African literature.[3][4]

Two cinema adaptations of the book have been made, the first in 1951 and the second in 1995. The novel was also adapted as a musical called Lost in the Stars (1949), with a book by the American writer Maxwell Anderson and music composed by the German emigre Kurt Weill.

Plot[edit]

The story begins in the village of Ixopo Ndotsheni, where the Christian priest Stephen Kumalo, a Zulu, receives a letter from the priest Theophilus Msimangu in Johannesburg. Msimangu urges Kumalo to come to the city to help his sister Gertrude, because she is ill. Kumalo goes to Johannesburg to help her and also to find his son Absalom, who had gone to the city to look for Gertrude but never came home. It is a long journey to Johannesburg, and Kumalo sees the wonders of the modern world for the first time.

When he gets to the city, Kumalo learns that Gertrude has taken up a life of prostitution and beer brewing, and is now drinking heavily. She agrees to return to the village with her young son. Assured by these developments, Kumalo embarks on the search for Absalom, first seeing his brother John, a carpenter who has become involved in the politics of South Africa. Kumalo and Msimangu follow Absalom's trail, only to learn that Absalom has been in a reformatory and will have a child with a young woman. Shortly thereafter, Kumalo learns that his son has been arrested for murder. The victim is Arthur Jarvis, a white man who was killed during a burglary. Jarvis was an engineer and an activist for racial justice, and he happens to be the son of Kumalo's neighbour James Jarvis.

Jarvis learns of his son's death and comes with his family to Johannesburg. Jarvis and his son had been distant, and now the father begins to know his son through his writings. Through reading his son's essays, Jarvis decides to take up his son's work on behalf of South Africa's black population.

Absalom reveals at his trial that he was pressured into committing the burglary by and with his three "friends", who later denied their involvement and threw Absalom under the bus. Absalom is sentenced to death for the murder of Arthur Jarvis. Before his father returns to Ndotsheni, Absalom marries the girl who is carrying his child. She joins Kumalo's family. Kumalo returns to his village with his daughter-in-law and nephew, having found that Gertrude ran away on the night before their departure.

Back in Ixopo, Kumalo makes a futile visit to the tribe's chief in order to discuss changes that must be made to help the barren village. Help arrives, however, when James Jarvis becomes involved in the work. He arranges to have a dam built and hires a native agricultural demonstrator to implement new farming methods.

The novel ends at dawn on the morning of Absalom's execution. The fathers of the two children are devastated that both of their sons have wound up dead.

Background[edit]

Cry, the Beloved Country was written before passage of a new law institutionalizing the apartheid political system in South Africa. The novel was published in 1948; apartheid became law later that same year.

The book enjoyed critical success around the world. It sold over 15 million copies before Paton's death.

The book is studied currently by many schools internationally. The style of writing echoes the rhythms and tone of the King James Bible. Paton was a devout Christian.

Paton combined actual locales, such as Ixopo and Johannesburg, with fictional towns. The suburb in which Jarvis lived in Johannesburg, Parkwold, is fictional but its ambiance is typical of the Johannesburg suburbs of Parktown and of Saxonwold. In the author's preface, Paton took pains to note that, apart from passing references to Jan Smuts and Sir Ernest Oppenheimer, all his characters were fictional.

Allusions/references to other works[edit]

The novel is filled with Biblical references and allusions. The most evident are the names Paton gives to the characters. Absalom, the son of Stephen Kumalo, is named for the son of King David, who rose against his father in rebellion. Also, in the New Testament Book of Acts, Stephen was a martyr who underwent death by stoning rather than stop declaring the things he believed. The Gospel of Luke and the Book of Acts are written to Theophilus, which is Greek for "friend of God".

In the novel, Absalom requests that his son be named "Peter", the name of one of Jesus's disciples. Among Peter's better-known traits is a certain impulsiveness; also, after Christ's arrest, he denied knowing Jesus three times, and later wept in grief over this. After the resurrection, Peter renewed his commitment to Christ and to spreading the Gospel. All that suggests Absalom's final repentance and his commitment to the faith of his father.

In another allusion, Arthur Jarvis is described as having a large collection of books on Abraham Lincoln, and the writings of Lincoln are featured several times in the novel.

Paton describes Arthur's son as having characteristics similar to his when he was a child, which may allude to the resurrection of Christ.