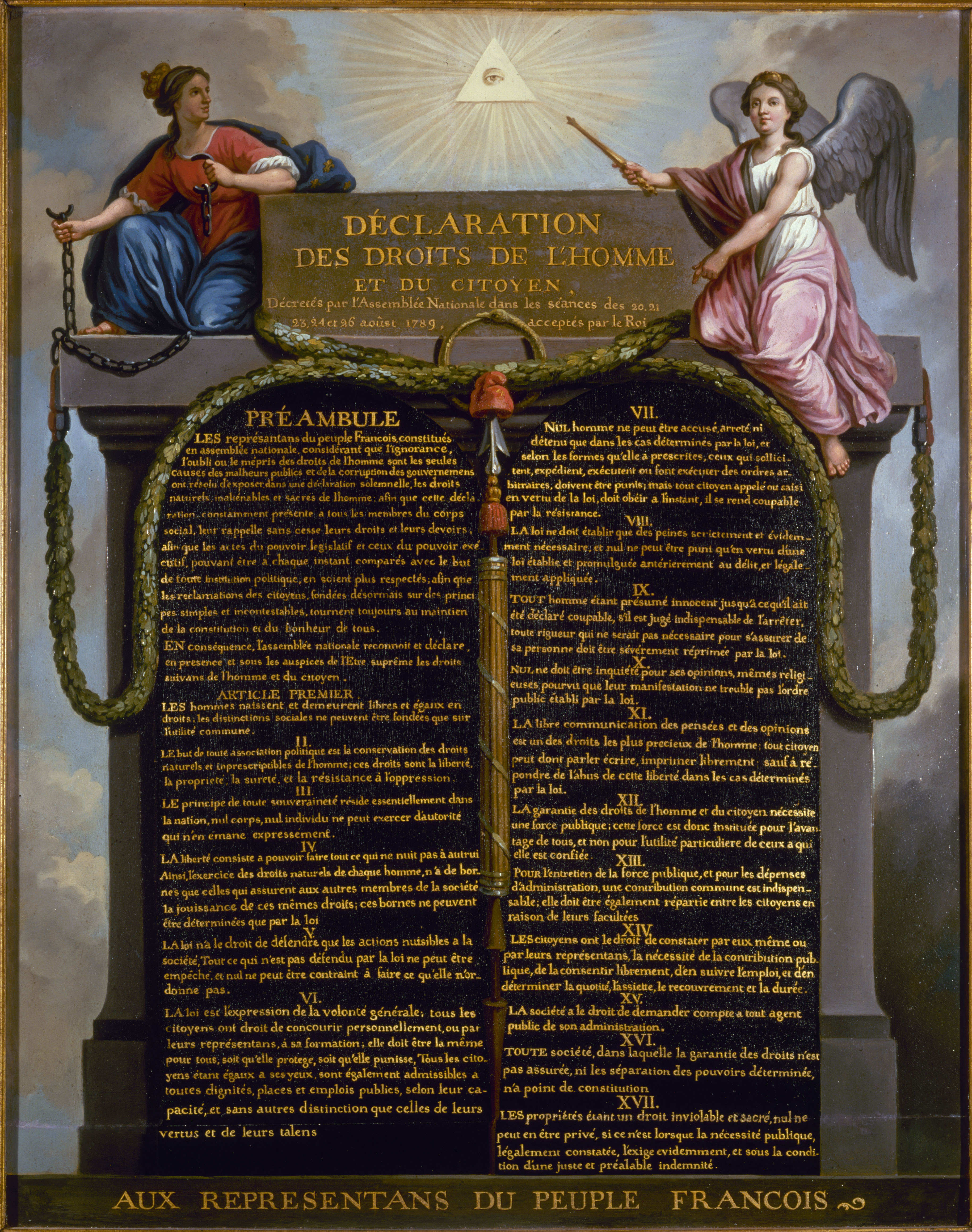

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (French: Déclaration des droits de l'Homme et du citoyen de 1789), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human civil rights document from the French Revolution.[1] Inspired by Enlightenment philosophers, the Declaration was a core statement of the values of the French Revolution and had a significant impact on the development of popular conceptions of individual liberty and democracy in Europe and worldwide.[2]

The Declaration was initially drafted by Marquis de Lafayette, with assistance from Thomas Jefferson, but the majority of the final draft came from Abbé Sieyès.[3] Influenced by the doctrine of natural right, human rights are held to be universal: valid at all times and in every place. It became the basis for a nation of free individuals protected equally by the law. It is included at the beginning of the constitutions of both the Fourth French Republic (1946) and Fifth Republic (1958), and is considered valid as constitutional law.

History[edit]

The content of the document emerged largely from the ideals of the Enlightenment.[4]

Lafayette prepared the principal drafts in consultation with his close friend Thomas Jefferson.[5][6] In August 1789, Abbé Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès and Honoré Mirabeau played a central role in conceptualizing and drafting the final Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.[3][7]

The last article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen was adopted on the 26 of August 1789 by the National Constituent Assembly, during the period of the French Revolution, as the first step toward writing a constitution for France. Inspired by the Enlightenment, the original version of the Declaration was discussed by the representatives based on a 24-article draft proposed by the sixth bureau,[8][9] led by Jérôme Champion de Cicé. The draft was later modified during the debates. A second and lengthier declaration, known as the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen of 1793, was written in 1793 but never formally adopted.[10]

Summary of principles[edit]

The Declaration defined a single set of individual and collective rights for all men. Influenced by the doctrine of natural rights, these rights are held to be universal and valid in all times and places. For example, "Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good."[19] They have certain natural rights to property, to liberty, and to life. According to this theory, the role of government is to recognize and secure these rights. Furthermore, the government should be carried on by elected representatives.[20]

When it was written, the rights contained in the declaration were only awarded to men. Furthermore, the declaration was a statement of vision rather than reality. The declaration was not deeply rooted in either the practice of the West or even France at the time. The declaration emerged in the late 18th century out of war and revolution. It encountered opposition, as democracy and individual rights were frequently regarded as synonymous with anarchy and subversion. This declaration embodies ideals and aspirations towards which France pledged to struggle in the future.[21]