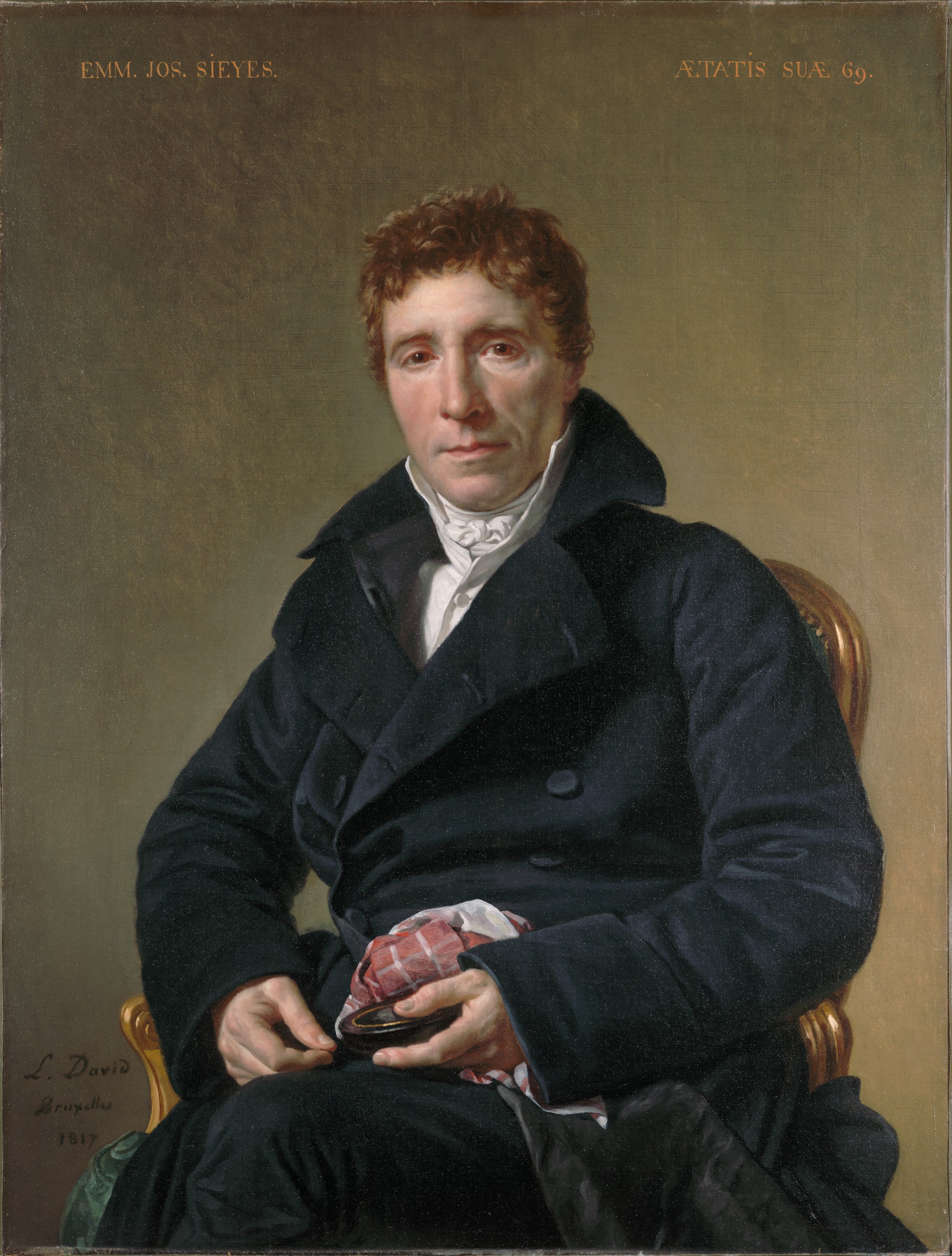

Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès

Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès (3 May 1748 – 20 June 1836), usually known as the Abbé Sieyès (French: [sjejɛs]), was a French Roman Catholic abbé, clergyman, and political writer who was the chief political theorist of the French Revolution (1789–1799); he also held offices in the governments of the French Consulate (1799–1804) and the First French Empire (1804–1815). His pamphlet What Is the Third Estate? (1789) became the political manifesto of the Revolution, which facilitated transforming the Estates-General into the National Assembly, in June 1789. He was offered and refused an office in the French Directory (1795–1799). After becoming a director in 1799, Sieyès was among the instigators of the Coup of 18 Brumaire (9 November), which installed Napoleon Bonaparte in power.

Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès

Office created

Jean-Jacques-Régis de Cambacérès (as Second Consul)

20 June 1836 (aged 88)

Paris, France

The Plain (1791–1795)

Priest, writer

In addition to his political and clerical life, Sieyès coined the term "sociologie", and contributed to the nascent social sciences.[1]

Early life[edit]

Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès was born on 3 May 1748, the fifth child of Honoré and Annabelle Sieyès, in the southern French town of Fréjus.[2] Honoré Sieyès was a local tax collector of modest income; although they claimed some noble blood, the family Sieyès were commoners.[2] Emmanuel-Joseph received his earliest education from tutors and Jesuits; and later attended the collège of the Doctrinaires of Draguignan.[2] His ambition to become a professional soldier was thwarted by frail health, which, combined with the piety of his parents, led to pursuing a religious career; to that effect, the vicar-general of Fréjus aided Emmanuel-Joseph, out of obligation to his father, Honoré.[3]

Education[edit]

Sieyès spent ten years at the seminary of Saint-Sulpice in Paris. There, he studied theology and engineering to prepare himself to enter the priesthood.[3] He quickly gained a reputation at the school for his aptitude and interest in the sciences, combined with his obsession over the "new philosophic principles" and dislike for conventional theology.[3] Sieyès was educated for priesthood in the Catholic Church at the Sorbonne. While there, he became influenced by the teachings of John Locke, David Hume, Edward Gibbon, Voltaire, Jean-Jaques Rousseau, Condillac, Quesnay, Mirabeau, Turgot, the Encyclopédistes, and other Enlightenment political thinkers, all in preference to theology.[4] In 1770, he obtained his first theology diploma, ranking at the bottom of the list of passing candidates – a reflection of his antipathy toward his religious education. In 1772, he was ordained as a priest, and two years later he obtained his theology license.[5]

Assemblies, Convention, and the Terror[edit]

Although not noted as a public speaker (he spoke rarely and briefly), Sieyès held major political influence, and he recommended the decision of the Estates to reunite its chamber as the National Assembly, although he opposed the abolition of tithes and the confiscation of Church lands. His opposition to the abolition of tithes discredited him in the National Assembly, and he was never able to regain his authority.[14] Elected to the special committee on the constitution, he opposed the right of "absolute veto" for the King of France, which Honoré Mirabeau unsuccessfully supported. He had considerable influence on the framing of the departmental system, but, after the spring of 1790, he was eclipsed by other politicians, and was elected only once to the post of fortnightly president of the Constituent Assembly.[9]

Like all other members of the Constituent Assembly, he was excluded from the Legislative Assembly by the ordinance, initially proposed by Maximilien Robespierre, that decreed that none of its members should be eligible for the next legislature. He reappeared in the third national Assembly, known as the National Convention of the French Republic (September 1792 – September 1795). He voted for the death of Louis XVI, but not in the contemptuous terms sometimes ascribed to him.[15] He participated to the Constitution Committee that drafted the Girondin constitutional project. Menaced by the Reign of Terror and offended by its character, Sieyès even abjured his faith at the time of the installation of the Cult of Reason; afterwards, when asked what he had done during the Terror, he famously replied, "J'ai vécu" ("I lived").[9]

Ultimately, Sieyès failed to establish the kind of bourgeois revolution he had hoped for, one of representative order "devoted to the peaceful pursuit of material comfort".[16] His initial purpose was to instigate change in a more passive way, and to establish a constitutional monarchy. According to William Sewell, Sieyès' pamphlet set "the tone and direction of The French Revolution … but its author could hardly control the Revolution's course over the long run".[17] Even after 1791, when the monarchy seemed to many to be doomed, Sieyès "continued to assert his belief in the monarchy", which indicated he did not intend for the Revolution to take the course it did.[18]

During the period he served in the National Assembly, Sieyès wanted to establish a constitution that would guarantee the rights of French men and would uphold equality under the law as the social goal of the Revolution; he was ultimately unable to accomplish his goal.

Directory[edit]

After the execution of Robespierre in 1794, Sieyès reemerged as an important political player during the constitutional debates that followed.[19] In 1795, he went on a diplomatic mission to The Hague, and was instrumental in drawing up a treaty between the French and Batavian republics. He resented the Constitution of the Year III enacted by the Directory, and refused to serve as a Director of the Republic. In May 1798, he went as the plenipotentiary of France to the court of Berlin, in order to try to induce Prussia to ally with France against the Second Coalition; this effort ultimately failed. His prestige grew nonetheless, and he was made Director of France in place of Jean-François Rewbell in May 1799.[9]

Nevertheless, Sieyès considered ways to overthrow the Directory, and is said to have taken in view the replacement of the government with unlikely rulers such as Archduke Charles of Austria and Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand of Brunswick (a major enemy of the Revolution). He attempted to undermine the constitution, and thus caused the revived Jacobin Club to be closed while making offers to General Joubert for a coup d'état.[9]

Second Consul of France[edit]

The death of Joubert at the Battle of Novi and the return of Napoleon Bonaparte from the Egypt campaign put an end to this project, but Sieyès regained influence by reaching a new understanding with Bonaparte. In the coup of 18 Brumaire, Sieyès and his allies dissolved the Directory, allowing Napoleon to seize power. Thereafter, Sieyès produced the constitution which he had long been planning, only to have it completely remodeled by Bonaparte,[9] who thereby achieved a coup within a coup – Bonaparte's Constitution of the Year VIII became the basis of the French Consulate of 1799–1804.

The Corps législatif appointed Bonaparte, Sieyès, and Roger Ducos as "Consuls of the French Republic".[20] In order to once again begin the function of government, these three men took the oath of "Inviolable fidelity to the sovereignty of the people; to the French Republic, one and indivisible; to equality, liberty and the representative system".[20] Although Sieyès had many ideas, a lot of them were disfavored by Bonaparte and Roger-Ducos. One aspect that was agreed upon was the structure of power. A list of active citizens formed the basis of the proposed political structure. This list was to choose one-tenth of its members to form a communal list eligible for local office; from the communal list, one-tenth of its members were to form a departmental list; finally, one further list was made up from one-tenth of the members of the departmental list to create the national list.[21] This national list is where the highest officials of the land were to be chosen.

Sieyès envisioned a Tribunat and a College des Conservateurs to act as the shell of the national government. The Tribunat would present laws and discuss ratification of these laws in front of a jury.[22] This jury would not have any say in terms of what the laws granted consist of, but rather whether or not these laws passed. The College des Conservateurs would be renewed from the national list. The main responsibility of the College des Conservateurs was to choose the members of the two legislative bodies, and protect the constitution by right of absorption. By this curious provision, the College could forcibly elect to its ranks any individual deemed dangerous to the safety of the state, who would then be disqualified from any other office. This was a way to keep a closer eye on anyone who threatened the state. The power of the College des Conservateurs was extended to electing the titular head of government, the Grand-Electeur. The Grand-Electeur would hold office for life but have no power. If the Grand-Electeur threatened to become dangerous, the College des Conservateurs would absorb him.[22] The central idea of Sieyès' plan was a division of power.

Napoleonic era and final years[edit]

Sieyès soon retired from the post of provisional Consul, which he had accepted after 18 Brumaire, and became one of the first members of the Sénat conservateur (acting as its president in 1799); this concession was attributed to the large estate at Crosne that he received from Napoleon.[23] After the plot of the Rue Saint-Nicaise in late December 1800, Sieyès defended the arbitrary and illegal proceedings whereby Napoleon rid himself of the leading Jacobins.[24]

During the era of the First Empire (1804–1814), Sieyès rarely emerged from his retirement. When Napoleon briefly returned to power in 1815, Sieyès was named to the Chamber of Peers. In 1816, after the Second Restoration, Sieyès was expelled from the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences by Louis XVIII. He then moved to Brussels, but returned to France after the July Revolution of 1830. He died in Paris in 1836 at the age of 88.

Contribution to social sciences[edit]

In 1795, Sieyès became one of the first members of what would become the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences of the Institute of France. When the Académie Française was reorganized in 1803, he was elected in the second class, replacing, in chair 31, Jean Sylvain Bailly, who had been guillotined on 12 November 1793 during the Reign of Terror. However, after the second Restoration in 1815, Sieyès was expelled for his role in the execution of King Louis XVI, and was replaced by the Marquis of Lally-Tollendal, who was named to the Academy by a royal decree.

In 1780, Sieyès coined the term sociologie in an unpublished manuscript.[1] The term was used again fifty years later by the philosopher Auguste Comte to refer to the science of society, which is known in English as sociology.[25] Sieyès was also among the first to employ the term science sociale.[26]

Personal life[edit]

Sieyès was always considered intellectual and intelligent by his peers and mentors alike. Through the virtue of his own thoughts, he progressed in his ideologies from personal experiences. Starting at a young age, he began to feel repulsion towards the privileges of the nobility. He deemed this advantage gained by noble right as unfair to those of the lower class. This distaste he felt for the privileged class became evident during his time at the Estates of Brittany where he was able to observe, with dissatisfaction, domination by the nobility.

Aside from his opinions towards nobility, Sieyès also had a passion for music. He devoted himself assiduously to cultivating music as he had plenty of spare time.[3] Along with cultivating music, Sieyes also enjoyed writing reflections concerning these pieces.[8] Sieyès had a collection of musical pieces he called "la catalogue de ma petite musique".[27]

Although Sieyès was passionate about his ideologies, he had a rather uninvolved social life. His journals and papers held much information about his studies but almost nothing pertaining to his personal life. His associates referred to him as cold and vain. In particular, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord remarked that "Men are in his eyes chess-pieces to be moved, they occupy his mind but say nothing to his heart."[28]